In 1968, graphic artist Rupert García became a pivotal figure in the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of Chicano, African American, Asian American, and Native students who held a major strike that year at San Francisco State College to demand ethnic studies programs and greater diversity in faculty and students. In later years, the protest had a significant impact on higher education in the United States, as more students demanded ethnic studies and universities eventually responded with new academic departments and teaching positions. Ethnic studies programs marshalled interdisciplinary methodologies focused on Latinx, African American, Asian American, and Native cultures and often told American and global histories through the lens of U.S. colonialism and imperialism, perspectives rarely incorporated in historical texts at that time. Several artists in ¡Printing the Revolution! shared a similar drive to reframe history. Their works explored alternative perspectives of national and global events, from the U.S Bicentennial to the rise of dictatorships in Latin America.

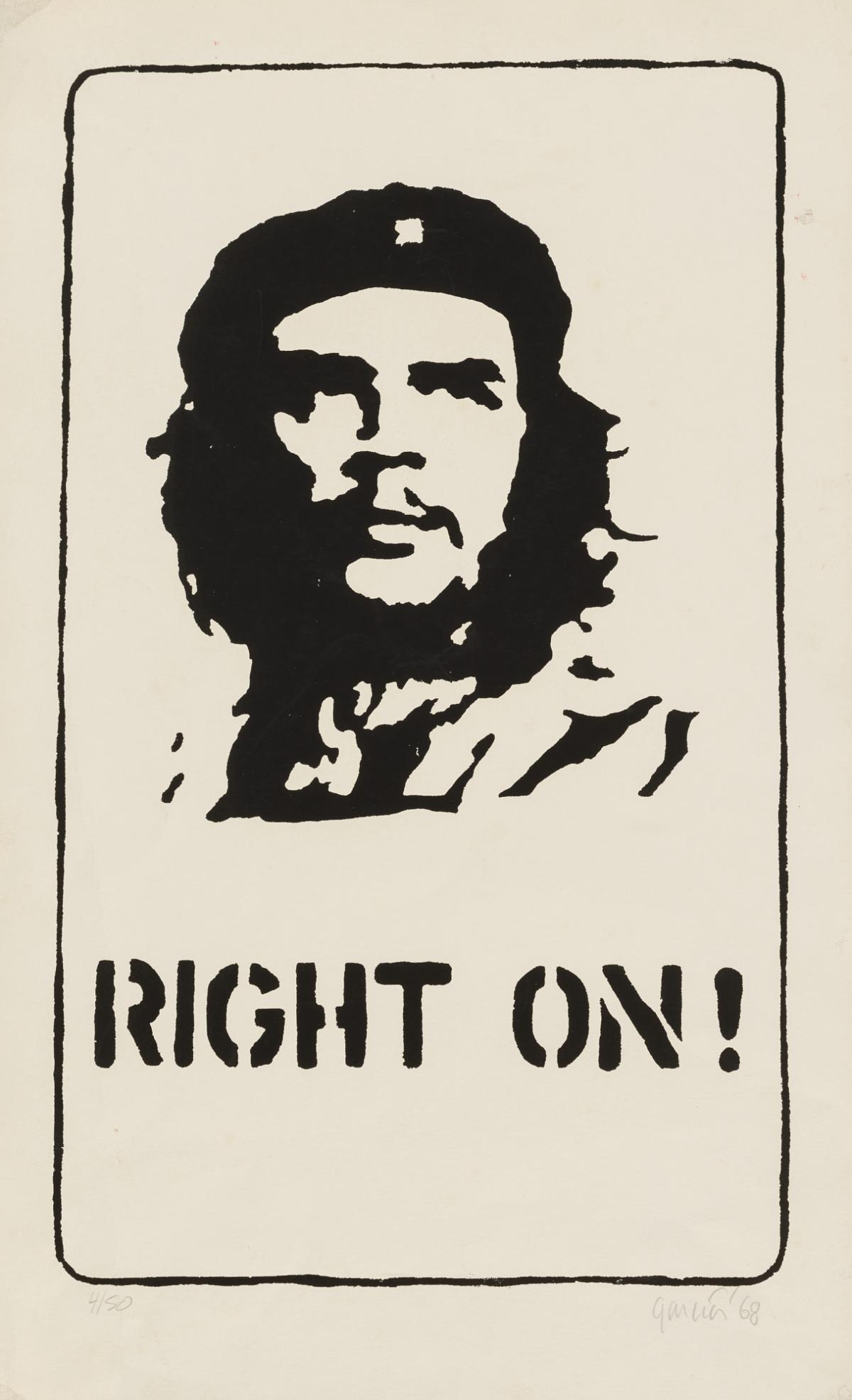

García’s Right On!, created in 1968 during the San Francisco State strike, is based on Alberto Korda’s photograph of Cuban revolutionary leader and icon Ernesto “Che” Guevara. Like San Diego artist Mario Torero, Chicano artists frequently reclaimed this Cuban figure to represent global resistance and revolutionary ideals. To capture the solidarity among the Third World Liberation students, García combined Che’s likeness with the popular Black Power slogan, “Right On!” This print reflects the artist’s signature graphic style of pop art sensibilities and forthright political statements. Early in the protest and related to the urgency of the moment, García created one-color screenprints like this. In fact, he created Right On! to raise funds for students’ bail funds, a common practice among political graphics of the time.

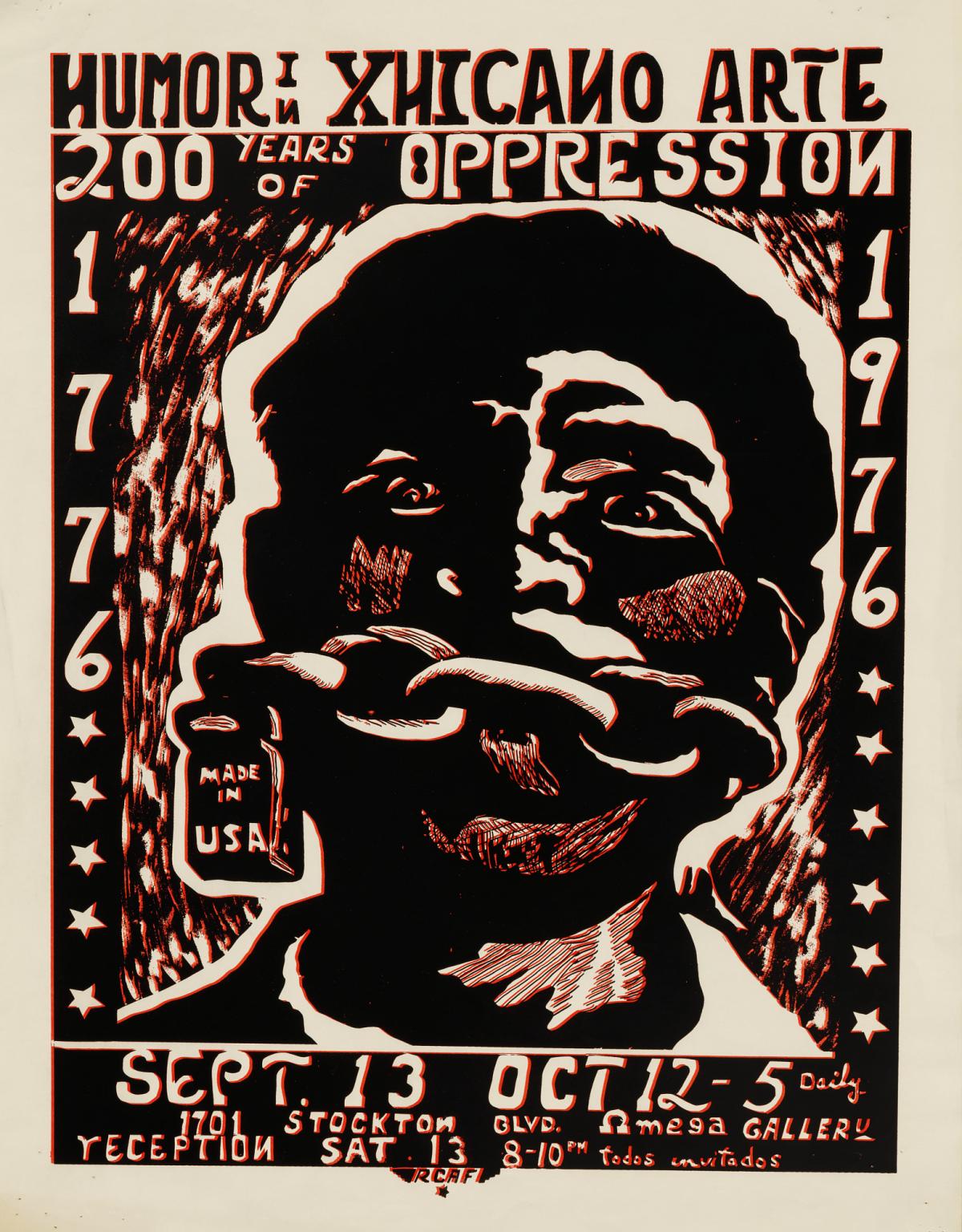

In 1976, as the the U.S. marked its Bicentennial, Chicano and other artists of color like Faith Ringgold questioned the celebratory rhetoric of this national anniversary, approaching it instead as a moment of solemn reflection. The Bicentennial commemorated the two hundred years since the republic’s creation when British colonies in North America overcame colonial rule. Rudy Cuellar, a member of the Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) art collective, challenged the national celebration’s overt patriotic imagery in his event poster, Humor in Xhicano Arte 200 Years of Oppression 1776-1976. The evocative scene focuses on a young Indigenous person chained with a padlock reading “Made in USA.” The chained figure is a remake of Mexican artist Adolfo Mexiac’s 1954/68 print protesting U.S. intervention in Guatemala and Mexican state violence. Many artists and activists like Cuellar, who lived through the early period of the civil rights movement, questioned whether all the people of the United States equally experienced freedom. His image of a gagged and chained figure resonated with the experiences of such figures as Bobby Seale and the San Quentin Six, who were gagged and chained, respectively, during their courtroom trials in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

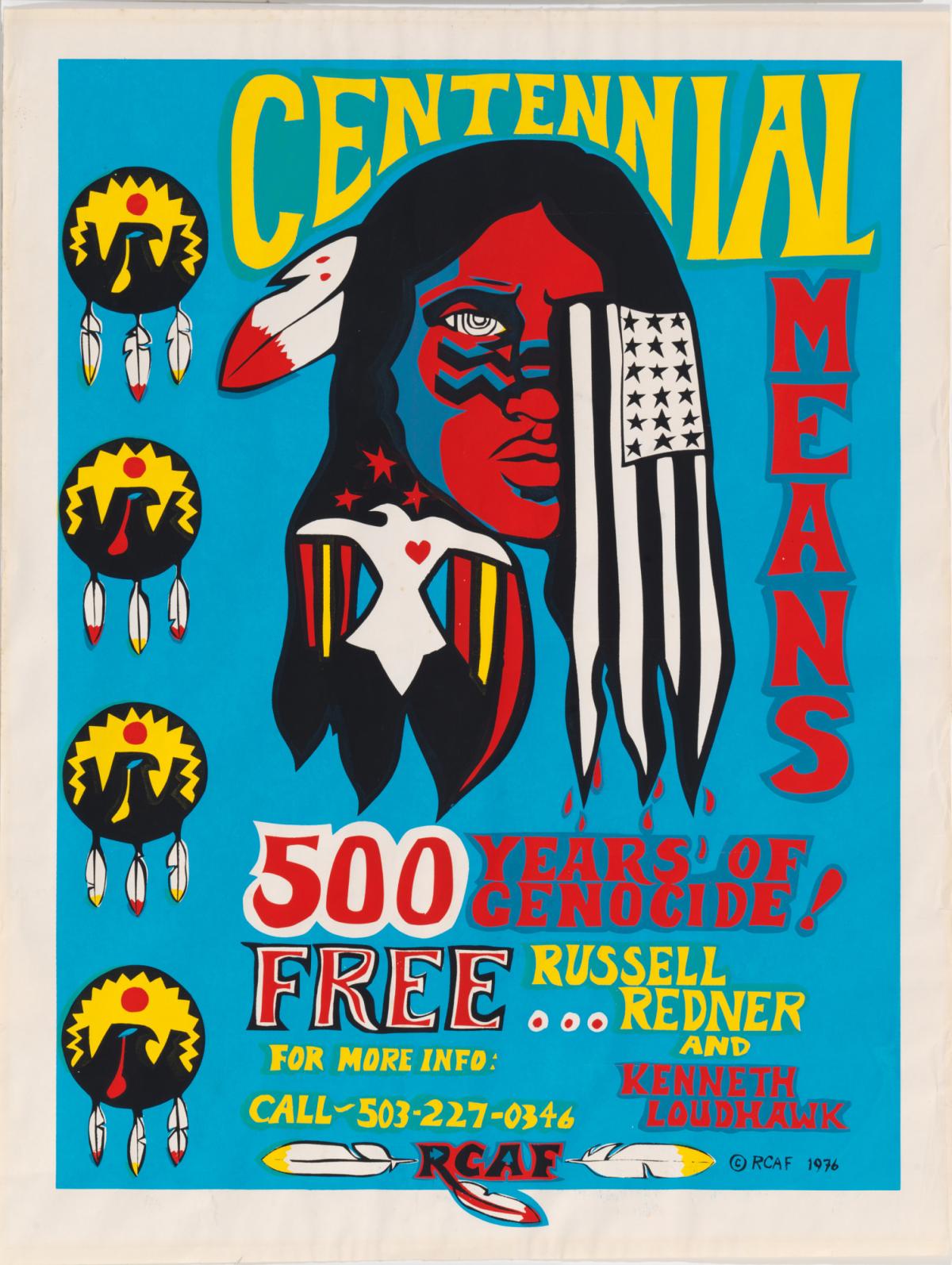

RCAF member Ricardo Favela’s 1976 print Centennial Means 500 Years of Genocide! calls for the release of Russell Redner and Kenneth Loudhawk, American Indian Movement activists arrested in 1973 after they participated in a staged protest at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Protesters at Wounded Knee demanded a review of Indian treaties and an investigation into the treatment of Native Americans in the United States. By juxtaposing a series of Lakota war shields with a Native figure whose face is partially obscured by a frayed U.S. flag and adding the words “500 years” and “centennial,” Favela conjures a long history of violent clashes between the United States and Indian nations. The print provides further information to support the activists’ release and acts as a reminder of the violent conquest of Native peoples across the Americas since 1492.

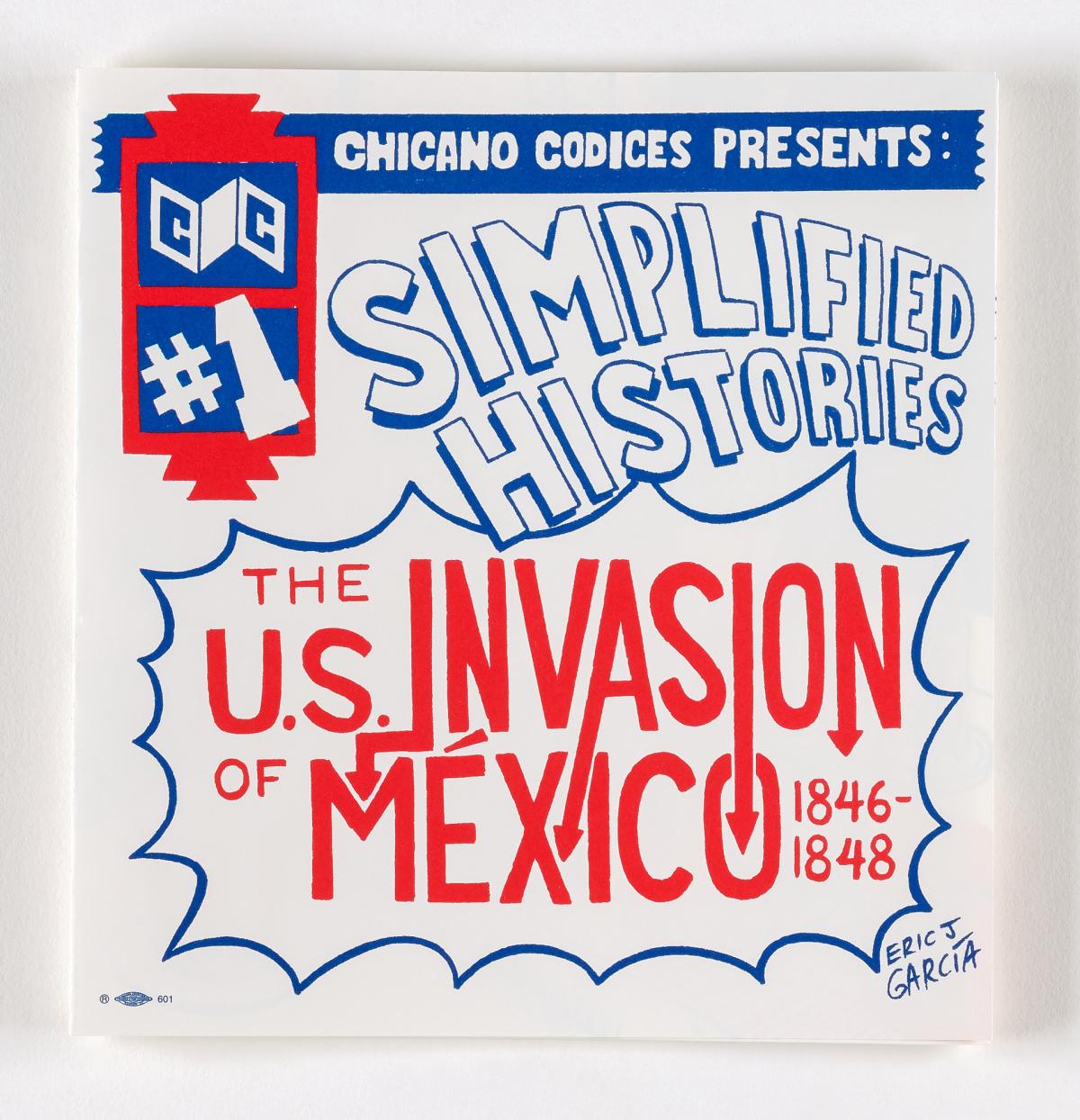

The history of Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States was destined to inhabit a large swath of North America “from sea to shining sea,” is a central themes for Chicano artists. The Mexican American War (1846-1848), which resulted in the United States annexing former Mexican territories in the Southwest and what would later become California to the U.S., is a recurring historical marker for Chicano artists. Like the RCAF, Eric García turns to a lauded historical moment and inverts its public reception. The artist’s personal experience as a member of the U.S. Air Force who was stop-lossed—given an involuntary extension of his active-duty service—led him to portray military critiques throughout his artistic career. In Chicano Codices, he uses the ancient and colonial accordion-style book form, the codex, and sequential art to reimagine this military history and critique the “victorious” U.S. through its common personification: Uncle Sam.

Chicano artists rethought other graphic forms as an entry point for historical and political reflections, employing familiar household objects such as the calendar. During the civil rights era, artists first adopted the calendar format because of its connection to Chicano daily life. Many artists grew up surrounded by illustrated calendars hanging in their homes. Given as gifts by local stores, they commonly portray scenes of Mexican Indigenous myths. Mexican commercial art from the 1940s and 1950s, which famously feature works by the painter Jesús Helguera, inspired the calendar genre. His paintings and illustrations are epic dramatizations of Mexican myths rendered in a classicizing realist style. These images continue to circulate today in calendars gifted by local businesses, like bakeries and mechanic shops.

In the United States, calendar prints, and in some cases, portfolios of twelve prints devoted to each month, served as a fundraising tool for artists, galleries, and print shops to make art available to community members at an affordable price. SAAM has an extensive collection of calendar prints, underscoring how artists were drawn to this format as a vehicle for historical awareness and international solidarity.

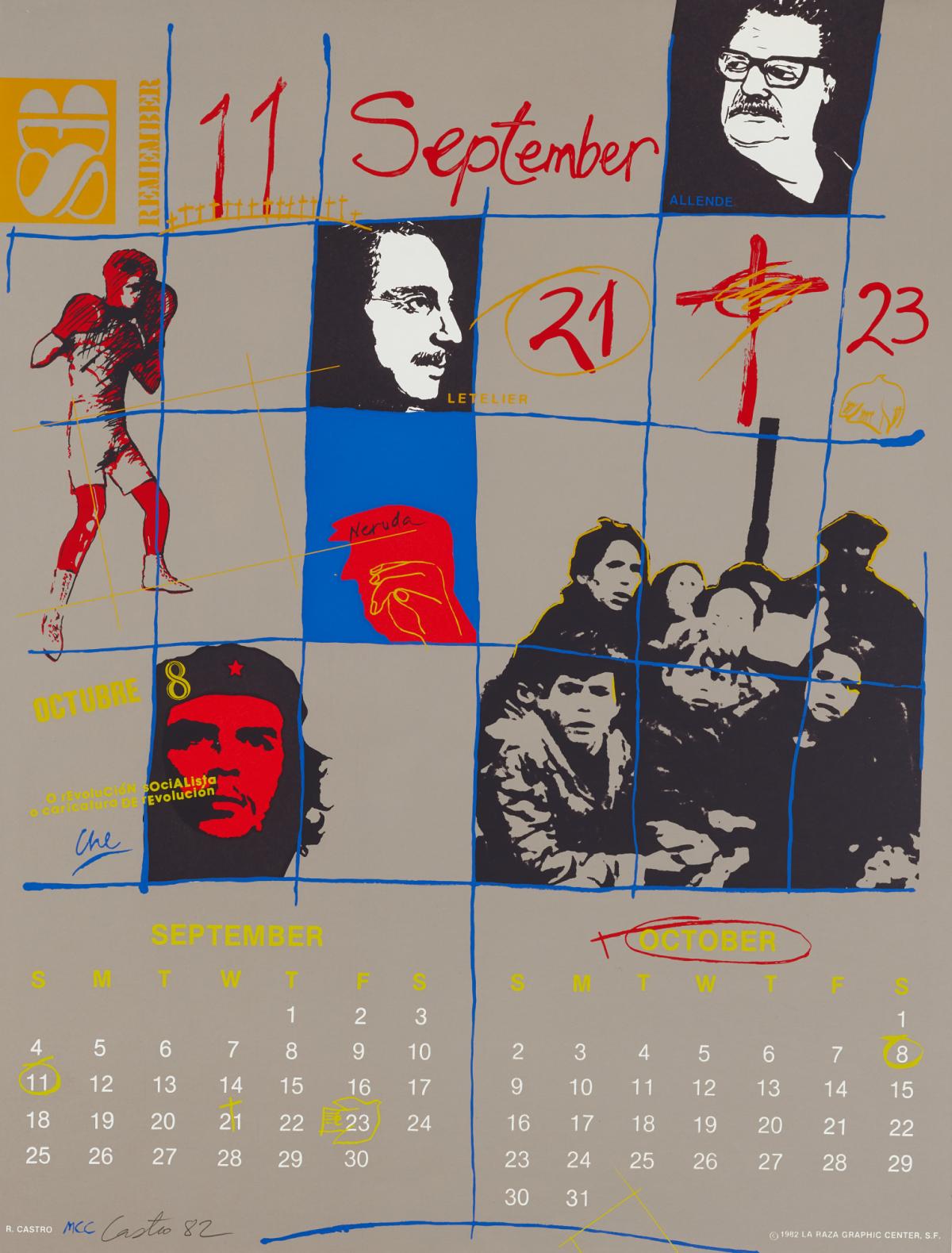

Artists used the calendar as an alternative to mainstream media and to expose U.S. involvement in key international events, like the Chilean military coup of 1973. Chilean artist René Castro used his print September/October from La Raza Graphic Center's 1983 Political Art Calendar to feature critical moments in Chilean history. He highlighted historical dates such as September 11, when Augusto Pinochet’s military violently overthrew the democratically elected Socialist Chilean president Salvador Allende in 1973. Other major moments in Castro’s calendar include Che Guevara’s death on October 9, 1967 and the assassination of Orlando Letelier, Allende’s exiled foreign minister in Washington, D.C., on September 21, 1976.

Castro was directly affected by these moments, having spent two years in a Chilean prison camp as a political prisoner. After this, he moved to San Francisco’s Bay Area as an exile and was active in Chicano print centers, like La Raza Graphics. He eventually founded Mission Gráfica, the print center within Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts (MCCLA), with fellow printmaker Jos Sances.

Artists in ¡Printing the Revolution! creatively subvert widely accepted historical narratives. These ongoing retellings of national and global histories are an essential part of democratic civic discourse. These works create platforms for new understandings of our national past and present.