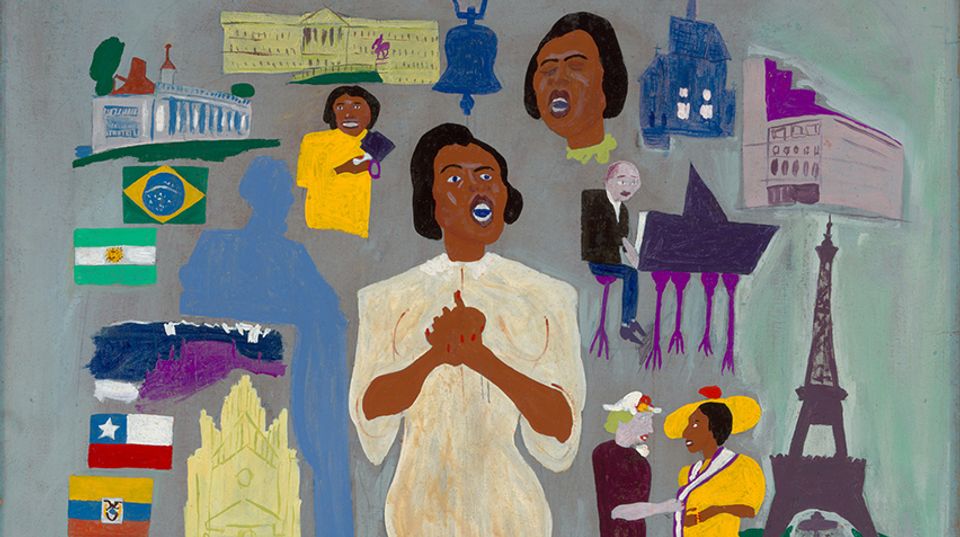

Himeko Fukuhara, Kazuko Matsumoto (Interned at Amache, Colorado, and Gila River, Arizona). Bird pins. Scrap wood, paint, metal. Collection of the National Japanese American Historical Society. From The Art of Gaman by Delphine Hirasuna, ©2005, Ten Speed Press.

"It all started because of this bird pin I'm wearing," Delphine Hirasuna told us the other day at the American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery in preparation for the March 5 opening of The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942–1946. Hirasuna, guest curator of the exhibition and author of the accompanying catalogue, was cleaning out her parents' home in California in 2000, following the death of her mother. In a box in the garage she found the colorfully painted wooden pin with wire legs and a safety-pin clasp wrapped in a box with trinkets her father had brought home from Italy, where he served with the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team during World War II. She knew then that this was a piece of art created during the time her parents were interned in makeshift camps—with 120,000 other Japanese Americans living on the West Coast—shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

When the evacuation orders were handed down, the people only had one week to comply. They could take only what they could carry but that had to include bedding and utensils for eating. One of the first things they did in the camps was to create objects for basic necessity: chairs, tables, places to hang their clothes. Many of the early objects were created for utility; the decorative arts followed as the war progressed. "Most of the things were made from scrap and found materials and were done by people who were not professional artists, and who went back to their careers—farmers, fisherman, shopkeepers—after the war," Hirusana told us, adding, "however, the level of talent and the variety of things was pretty amazing to me."

Thanks to the bird pin she discovered, Hirasuna began looking for other objects created in the internment camps, which was not an easy task. Many Japanese Americans did not discuss their time in the camps with their children, and the arts and crafts they created were often done as busywork, and were discarded or packed up and hidden in garages and attics after the war. Hirasuna knew about the bird pins and corsages made of shells, but as she found other objects she was dazzled by the range of materials, including slate, rocks, and fabric. The bird pins were made of scrap lumber that was found in the camps as well as wire that was used to cover barrack windows. The artists used images of birds found in old copies of National Geographic magazines as their models. The beautiful pins seem to belie the circumstances under which they were created and exemplify the definition of gaman: enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.

The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942–1946 is on view at our Renwick Gallery and runs through January 30, 2011.