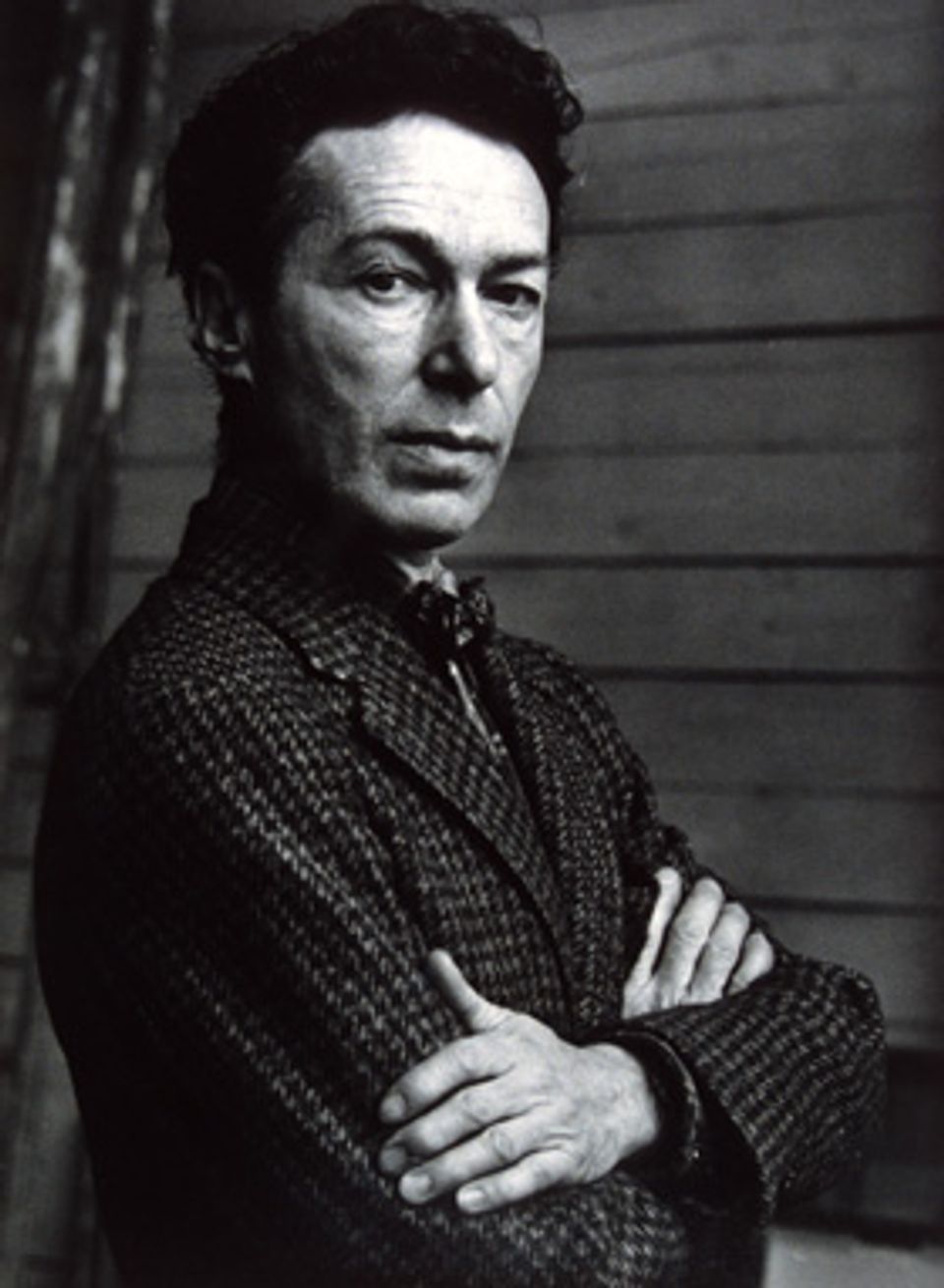

Hananiah Harari

- Biography

Born in New York. Has led a double life as both an abstract painter whose work has been exhibited in museums and as a commercial artist who has designed print advertisements and magazine covers.

Nora Panzer, ed. Celebrate America in Poetry and Art (New York and Washington, D.C.: Hyperion Paperbacks for Children in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1994)

- Artist Biography

A native of Rochester, NewYork, Harari began to paint while still a teenager. He studied first at the Rochester Memorial Art Gallery, and from 1930 to 1932 at the School of Fine Arts at Syracuse University. In Paris in 1932, he studied with Fernand Léger, André Lhote, and Marcel Grommaire. Through portraitcommissions Harari was able to extend his stay on the city's Left Bank for several years. In Paris, Harari sought out Impressionist and Old Master paintings as well as modern works. He spent a year doing copy drawings from the collections of the Louvre. After a trip to Palestine, "where visual richness but little hard cash awaited him," he returned to the United States in 1935. Harari settled in New York City, and joined the circle of young abstractionists working on the WPA's mural project under Burgoyne Diller. For Harari, as for a host of others, the WPA experience provided unencumbered time to develop their art "in an environment of purpose and animation. . . ."(1)

After returning to New York, Harari became involved in the vanguard circle of the American Abstract Artists. Never a doctrinaire abstractionist, even in the early years of his career, Harari moved freely between abstraction and a lyrical expressionism that incorporated figurative elements. This is apparent in his Sparklers on the Fourth [SAAM, 1986.92.55] and Jacob Wrestling with the Angel [SAAM, 1986.92.52]. Harari was unwilling to relinquish the rich possibilities the natural world offered. Moreover, the strict avoidance of recognizable forms advanced by geometric abstractionist members of the American Abstract Artists (Ad Reinhardt for one), precluded expression of Harari's irrepressible wit. Their approach, he wrote, "denied too much of art's potential and too many of its glories; in elevating neatness and order to a high altar, it failed to give adequate weight to the enriching concept of random upset (disorder, derangement, derailment)—a phenomenon abounding in all of life. I could not accept the idea that a formally pure art in and of itself denoted an evolutionary advance over an art of forms rooted in the natural world; to the contrary, I saw the former not leading forward, but, within its logic, veering toward a void."(2)

Within the American Abstract Artists, Harari was by no means alone in his unwillingness to renounce themes drawn from his experience of the world. In a letter to the editor of Art Front, drafted by Harari, and signed also by George McNeil, Byron Browne, Rosalind Bengelsdorf, Leo Lances, Herzl Emanuel, and Jan Matulka, the group declared: "It is our very definite belief that abstract art forms are not separated from life, but on the contrary are great realities, manifestations of a search into the world. …"(3) This desire to connect with the world at large is apparent not only in Harari's paintings but also in various letters to editors he wrote during this first decade of his career.(4) Social and political concerns, and a desire to educate those unfamiliar with modern art, color his philosophy about art's significance and potential. Several paintings from the late 1930s and early 1940s reflect his horror at the political oppression and social atrocities takingplace in Germany.

Around 1939, Harari became fascinated with William Harnett, and began doing trompe l'oeil paintings. Several of these he also executed according to a Cubist vocabulary. A 1939 painting entitled Man's Boudoir, a trompe l'oeil painting of a table top with the accoutrements of a man's toilette that won the first Hallgarten Prize at the National Academy of Design's 1942 annual exhibition, has, as a pendant, a Cubist version of the same subject.(5)

Throughout Harari's work there is whimsy and wit, and an abiding desire to express a joie de vivre.Sparklers on the Fourth was made from sketches done during the summer of 1940 when Harari, his wife, and several friends were celebration Independence Day. "It was a mild night. The national flag was raised in the center of the lawn. The brilliant lights of the pyrotechnics pierced the darkness and illuminated the flag and my companions, who, abandoned themselves to the occasion and engaged themselves in running spontaneously about while holding the blazing sparklers in their hands, thus etching streaks of light against the night. . . . This scene had in it magic and beauty. . . ."(6) In the painting, Harari captures the light that pierced the dusky night. Laying dark pigment over a white ground, he etched into the painting's surface, using the whiteness of the ground to illuminate the nocturnal scene.

In 1943, Harari was inducted into the army, and at that time he ended his association with the American Abstract Artists. An active, early member of the group, Harari's artistic interests after the war no longer coincided with the group's program.

1. Hananiah Harari, "WPA–AAA, "handwritten reminiscence of his experience on the WPA provided by Harari, in the curatorial files, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

2. Hananiah Harari, "WPA-AAA," handwritten reminiscence of his experience on the WPA provided by Harari, in the curatorial files, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

3. "To the Editors," Art Front 3, no. 7 (October 1937): 20–21.

4. See "Who Killed the Home Planning Project?" Art Front 3, no.8 (December 1937): 13–15.

5. For illustrations of both versions of Man's Boudoir, see Greta Berroan and Jeffrey Wechsler, Realism and Realities: The Other Side of American Painting (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Art Gallery, 1981), p.173.

6. Hananiah Harari, letter to Walter Baum, February 1946, courtesy of the artist, copy in the curatorial files, National Museum of American Art.

Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)

Luce Artist BiographyHananiah Harari traveled to Palestine in 1934 with the sculptor Herzl Emanuel, where they worked on a kibbutz and visited Jerusalem and the Sea of Galilee. Two years later Harari was a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, a group established in New York to promote nonobjective art. He rejected pure abstraction, however, because it was “separate from life,” and many of his images incorporate recognizable objects such as figures, architecture, or machinery. Harari worked as a graphic artist after World War II, creating advertisements and illustrations for magazines and newspapers. But he was blacklisted during America’s “Red scare” because he also drew political cartoons for leftist publications. (Hananiah Harari: Abstractions from the 1940s, Exhibition Catalogue, Richard Norton Gallery, 2004)