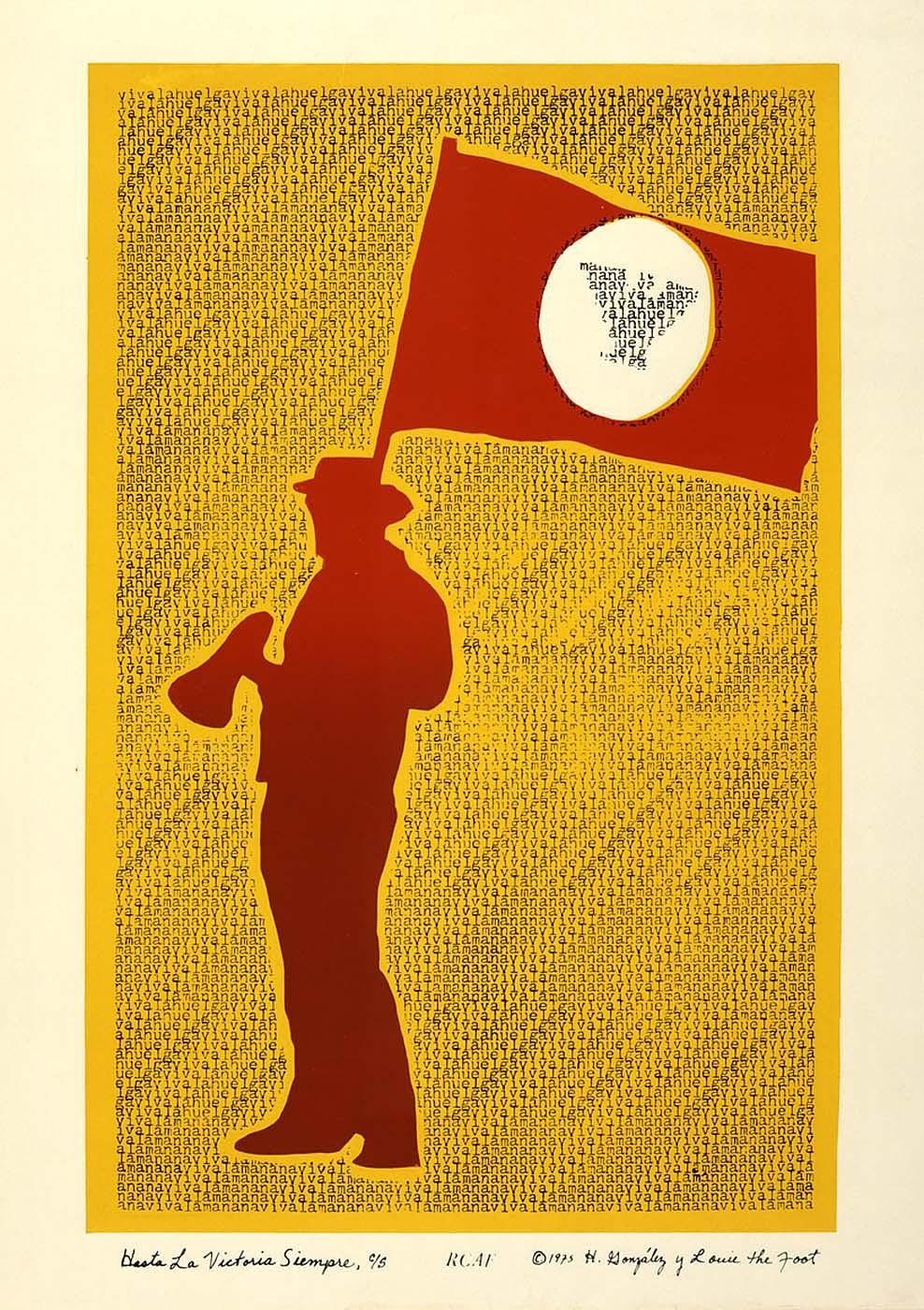

Hasta La Victoria Siempre by brothers Luis C. González (also known as Louie “The Foot” González) and Héctor D. González, combines eye-catching design, poetry, and international politics. During the Chicano Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Luis González, as well as other artists in the movement, produced banner-like works in support of social and economic rights for farm workers. Central to this image is a silhouetted figure holding a United Farm Workers (UFW) flag. Typewritten letters spelling out Chicano rallying cries form the background. In combining vivid graphic design that would attract attention from a distance with typography that formed visual poetry, artists drew in viewers and gave additional meaning to the work when it was examined close-up.

In her essay “Aesthetics of the Message: Chicano/a Posters, 1965-1987” for the exhibition catalogue, art historian and curator Terezita Romo explores how Luis González uses form to convey meaning in his poster. The economy of imagery and colors, using simple but bold red and yellow, belies the complexity of its message and graphic innovation. The figure, taken from a photograph by Luis’s brother, Héctor, is the notable Chicano artist and activist José Montoya, who is holding a UFW flag during the 1971 La Marcha de la Reconquista, a historic 800-mile long political march by Chicano activists. By pairing the image with text, González uses both the visual, as well as the literal, language of protest. The poster begins to function as a concrete poem, a visual form of poetry where the shape and the form of the text matches its subject in order to heighten its aesthetic power. Seemingly random letters coalesce into the phrases “Viva la huelga” (long live the strike), a rallying cry at UFW strikes, and “Viva la mañana” (long live tomorrow). The phrases form the poster’s background and add motion, texture, and social meaning. The same text in the flag forms the shape of the United Farm Workers’ logo, itself based on the Aztec eagle from the Mexican flag that would be an instantly recognizable symbol to the Mexican and Mexican American farm workers.

1975, the year Luis González made his poster, was a pivotal one for the UFW. The organization was still leading boycotts on Gallo wine, grapes, and lettuce and was integral in championing California’s landmark agricultural labor legislation, which, among other liberties, gave farm workers the right to organize. The title of the poster, Hasta la Victoria Siempre (“Until Victory, Always!”), is drawn from Che Guevara’s well-known phrase for the Cuban Revolution. By referencing the revolutionary figure, González’s poster elevates farm workers’ rights to be equal to other international struggles, which (according to the title) will continue until the promise of a better future for farm workers is fulfilled.

SAAM’s landmark exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, explores how Chicanx artists have linked innovative printmaking practices with social justice. This blog post is part of series that takes a closer look at selected artworks with material drawn from exhibition texts and the catalogue.