Guest blogger Jean Lawlor Cohen is the consulting curator for Gene Davis: Hot Beat. She is an arts writer, independent curator, and co-author of Washington Art Matters: Art Life in the Capital 1940-1990.

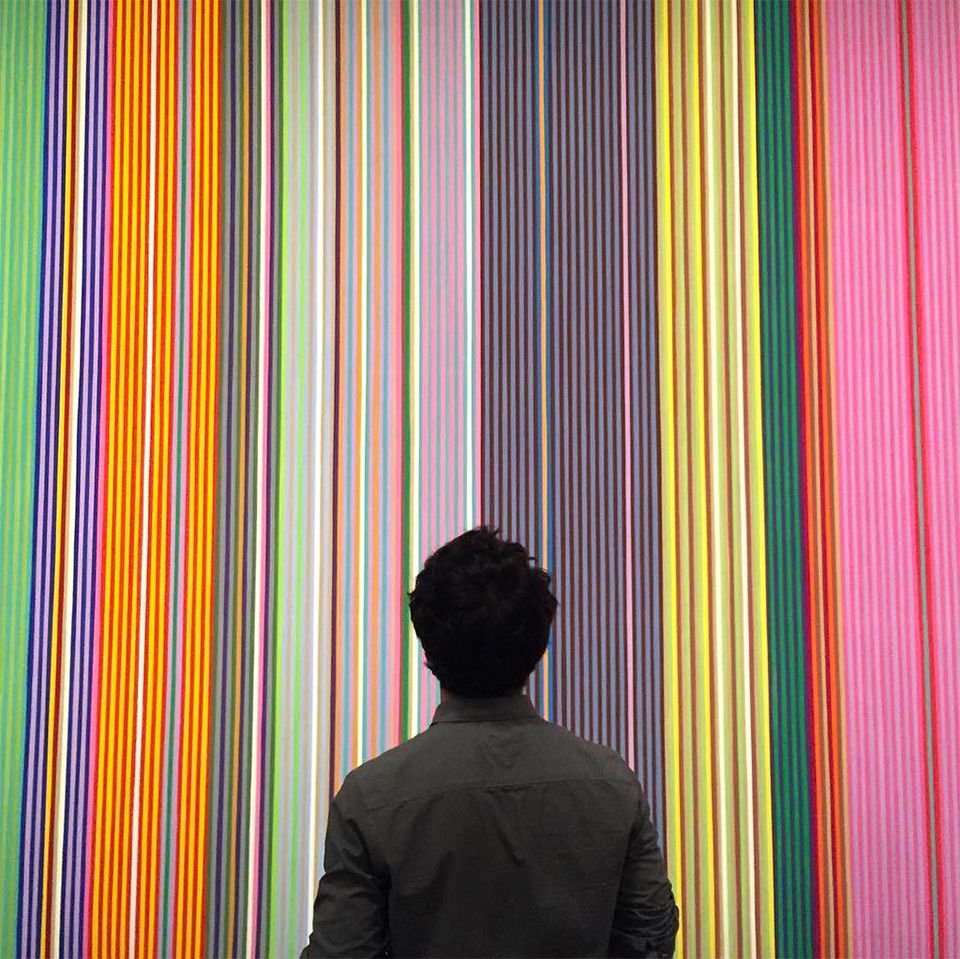

Gene Davis, a journalist before he was a painter, knew the power of words. He spoke his wise and sometimes ornery mind, aware of the momentary impact and the eventual documentation of his life and career. This explains why his own bon mots (not the curators') flank most of the 15 paintings—all permutations of the stripe—in Gene Davis: Hot Beat, on view through April 2.

Interviews especially mattered to him. He enjoyed giving the press nuggets he had honed, quotes that read jargon-free, and he spoke for hours to historians who taped him for the Archives of American Art. He came to his maxims as he stuck to a self-imposed regimen ("early to bed," paint until noon), then filled his off-hours with teaching at the Corcoran School of Art or making lyrical, quirky drawings, seeing foreign films, reading the art critics (most of them parasitic and myopic, he said), and inviting friends to his studio and his dinner table.

In social conversation, Davis revealed a love of children's art (often rescued from the trash bin of a nearby nursery school), Mozart and the Sex Pistols, a passion for the Washington football team, and for the white XJE Jaguar he tested on a nearly empty Dulles airport access road. With sly humor, he named his slow-witted basset hounds "Gerry" for museum director Gerald Nordland and "Barney" for the admirable artist Barnett Newman. His parakeet was "Clem" for troublesome art critic Clement Greenberg.

Anyone who spent time with Davis heard stories of his White House correspondent years: how he played poker with President Truman on cross-country train trips or stood in the Oval Office on D-Day. He liked to call himself "an old newspaper man," and maybe some of that journalistic objectivity had kept him dogged and curious. Years later, when Davis left his post as an editor for the American Automobile Association to focus on painting, he already had a measure of national fame. With supportive wife Florence Coulson, he lived in a northwest D.C. colonial and added a below-grade studio, its transom shutters permanently closed against natural light. To explain himself, Davis liked to quote the advice of Gustave Flaubert: "Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work."

Indeed control marked his lifestyle: the shaven head (he was not totally bald), the insistence on punctuality, the precisely edged lawn and mulch beds, his all-white walls, the carefully positioned canvases and small sculptures, even the territorial limits imposed on his basset hounds. It was this sense of order that made the stripe "right" for him. He found in that vertical form an "exquisite monotony," a freedom from composing and "an uncompromising quality, a rectitude."

Even though Davis had abandoned turbulent 1950s expressionism for formal geometry, he held onto what he said distinguished his color works: their "most important quality...whim." He claimed to never plan a painting or make a preliminary drawing. "My whole approach is intuitive. Sometimes I simply use the color I have the most of and worry about getting out of trouble later. Perhaps I'm like the jazz musician who can't read music but plays by ear. I paint by eye."

To learn more about Gene Davis and the colorful art world of the 1960s, join us at SAAM for a panel discussion on Thursday, January 12, 2017, at 6:30 p.m. I'll moderate a conversation with Benjamin Forgey, independent art critic and former Washington Post art and architecture critic; Jack Rasmussen, director of the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, who curates many exhibitions inspired by Washington art history; and Paul Richard, Washington Post art critic from 1967 to 2009, who has personal insights and stories about Davis and other artists active in D.C.

If you can't make it to the talk, watch the webcast: Washington Art Scene in the ’60s Discussion. And be sure to take a look at John Kelly's piece in The Washington Post about Gene Davis and his connection to the D.C. art community.