This post is part of an ongoing series on Eye Level: Q and Art, where American Art's Research department brings you interesting questions and answers about art and artists from our archive.

Question: Who was Stanton Macdonald-Wright and what was the Synchrome Kineidoscope?

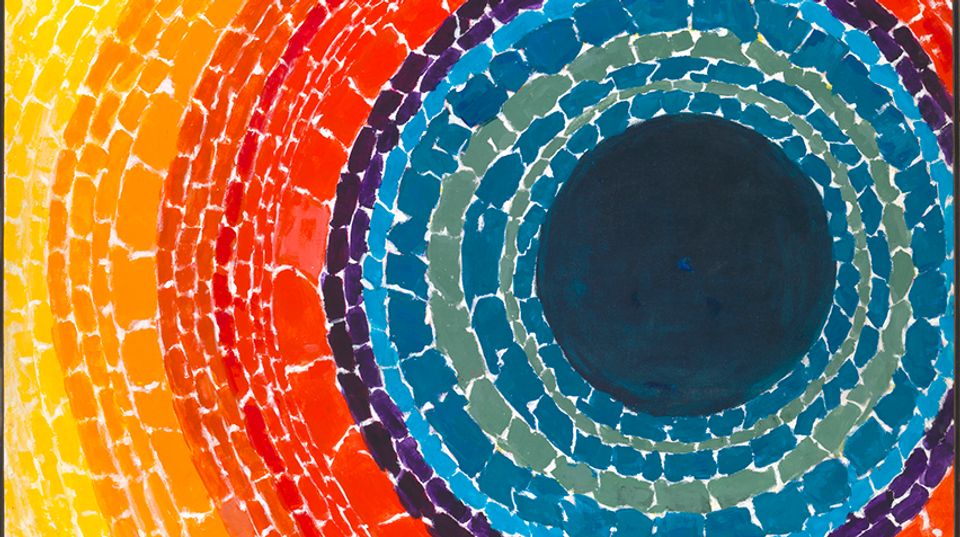

Answer: Stanton Macdonald-Wright (1890-1973) was an American painter, writer, experimental artist, and teacher most well-known for the abstract painting style called Synchromism, which he developed with fellow American painter Morgan Russell.

Born in Virginia and raised in California, Macdonald-Wright began taking art lessons at age five and later studied at the Art Students League of Los Angeles. In 1909 Macdonald-Wright moved to France to study art with the masters. He attended lectures at several respected art schools; however, he reported learning the most from artworks he saw in museums and galleries throughout Europe. He met Russell in 1911, and the two artists found they had compatible ideas about modern art with a shared interest in making paintings in which only color created the form. They began studying with painter and color theorist Ernest Percyval Tudor-Hart who taught about the correlation between color and music. Macdonald-Wright and Russell advanced Tudor-Hart's theories and created a style of painting they called Synchromism. They gave their paintings titles such as "Synchromy in Blue" or "Sunrise Synchromy in Violet". The word 'synchromy' intentionally calls to mind its musical equivalent: symphony. Macdonald-Wright and Russell promoted Synchromism as a system that allowed the artist to select and arrange colors to create color scales and harmonies just as a musician would combine musical notes to create a piece of music.

A continuation of the music metaphor led the painters to consider how they could make a painting exist and change through a period of time. Their answer to this quandary was the Synchrome Kineidoscope, a color and light projecting machine that Macdonald-Wright and Russell first envisioned in 1913. The artists discussed the Kineidoscope often, and they continued to correspond about it after Macdonald-Wright returned to California and both artists had diverged from the synchromist style. During the decades after Synchromism, Macdonald-Wright's career included many projects such as planning exhibitions, mural making, teaching and being an administrator for an art school and the WPA's Federal Art Project, but he continued to work on his idea for the Kineidoscope. His efforts were often thwarted by a lack of funds and technological knowledge, but eventually with the assistance of a professional firm, he developed his art machine. The first version of the Kineidoscope was completed in the late 1950s around the same time that Macdonald-Wright resumed making synchromist inspired paintings.

In 1967, the Smithsonian American Art Museum held a retrospective of Macdonald-Wright's work. As part of the exhibition, the artist traveled to Washington and demonstrated his Synchrome Kineidoscope. According to the invitation for one of the three demonstrations, this was the first time that the machine was presented to a public audience. A reporter for the Washington Post described the complicated device and its effect: "Four projectors, three 35 millimeter black and white films (two of which cross each other behind a projector) and a color 'control' are involved in a process of 17 different operations, which send overlapping color shapes marching across the screen in different directions, make them disappear in a fade-out, or transformation or 'mutation' of color 'key'". Although Stanton Macdonald-Wright's Synchrome Kineidoscope is not often remembered today, its conception in the 1910s and development in the 1950s was a forerunner of the film and media based artworks of the 20th and 21st centuries.

To read more about Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Synchromism look for the following books and article at your library or bookstore: Color, Myth, and Music: Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Synchronism by Will South, The Art of Stanton Macdonald-Wright, (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Press, National Collection of Fine Arts, 1967), and "Artist Arrives With a Picture Machine" by Andrew Hudson, Washington Post and Times Herald from May 25, 1967.