The Renwick Gallery's Grand Salon

This post is part of an ongoing series on Eye Level: The Best of Ask Joan of Art. Begun in 1993, Ask Joan of Art is the longest-running arts-based electronic reference service in the country. The real Joan is Kathleen Adrian or one of her co-workers from the museum’s Research and Scholars Center. These experts answer the public's questions about art. Earlier this year, Kathleen began posting questions on Twitter and made the answers available on our Web site.

Question: I was visiting the Renwick Gallery's Grand Salon and wanted to know why the works were displayed so differently from the other gallery exhibits?

Answer: Referred to as "salon style," the concept of this type of picture gallery began in the early Renaissance and remained popular through the late nineteenth century. In this installation method, pictures are displayed in such a way that the walls are almost completely covered by works of art. In many cases, large paintings were hung on the center of the walls, surrounded by smaller works.

One extreme example of the "salon style" occurred in London in the 1880s, when James McNeill Whistler decided to not only display his artwork in this manner, but also coordinated the colors of baseboards and gallery walls, and made sure the rugs, tables and even the guards's uniforms didn't clash with the art on display.

In many instances, frames were placed so close to other frames that there was no room for labels. At best, each painting was identified by a number keyed to a checklist providing the artist's name and the work's title.

Lighting was also a problem for these "salon style" picture galleries. In general, most were lit by skylights, although by the late nineteenth century many commercial art galleries were using gaslight in order to stay open in the evening. Whatever the source of illumination, many works were either underlit or overlit.

By the 1960s, the "salon style" of hanging artwork had almost completely disappeared in favor of the "white cube" style, first promoted by influential exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s. Once the plain "white cube" arrived it became, as artist, art critic, and academic Brian O'Doherty wrote, an "aesthetic force" implying that the art you saw within it was being presented "as clearly and objectively as research specimens in a science lab," in sharp contrast to the salon-style gallery's ornate and more intimate spaces.

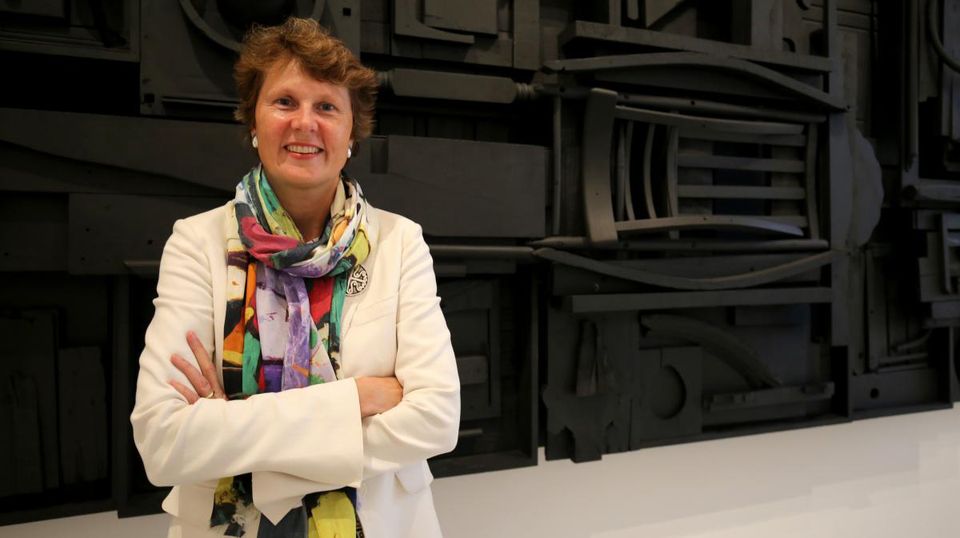

The Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery refurbished our Grand Salon in 2000. Visitors to the museum can continue to experience this salon style hanging of paintings from the museum's collection, top-to-bottom and side-by-side, recreating the elegant setting of a nineteenth-century collector's picture gallery.

For more information about this style of displaying art, you might want to consult books on the 19th century salons, such as: Charles Baudelaire's and Jonathan Mayne's Art in Paris, 1845-1862: Salons and other exhibitions, Lois Marie Fink's American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons, and Elizabeth Basye Gilmore Holt's The Art of All Nations, 1850-73: The emerging role of exhibitions and critics. You might also take a look at two articles on "salon style" and "white cube" installations: John Kenneth Myers's "Mr. Whistler's gallery: the art of displaying art." in the November 2003 issue of Magazine Antiques, and Peter Plagen's "Return of the White Cube" in the February 2005 issue of Art Review.

If you want to see the Renwick's Grand Salon in all its holiday finery, plan on attending both the Winter Wishing Tree (where you can help decorate our annual holiday tree) and the Renwick Holiday Festival. The Wishing Tree will be December 1–3, 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and the Festival will be Saturday, December 4, 11 a.m to 2 p.m.