An object labeled a “gold and glass Byzantine necklace from the sixth century” entered SAAM’s collection in 1929, but under closer study, conservators now believe it’s more likely a nineteenth century imitation or forgery. How can we tell the difference? And why is it at the Smithsonian American Art Museum?

In 1929, the art collector John Gellatly donated a large collection of paintings, jewelry, and decorative arts to the Smithsonian’s “National Gallery of Art” (now SAAM), which included the necklace in question. Gellatly had broad art historical interests, collecting American paintings as well as European, Asian, and archaeological objects. After 76 years in storage, the necklace was installed in our Luce Foundation Center in 2006 and most recently in 2021 is included in the Sargent, Whistler, and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano exhibition. This gave us the opportunity to bring the unusual object to SAAM’s Lunder Conservation Center in 2019.

When investigating a mysterious artwork, we often start with three areas: materials, style, and provenance. Provenance is the history of an object’s ownership and location. We can only trace this necklace’s provenance as far back as 1929 when it entered our collection, but our files don’t contain any record of where or when Gellatly purchased it. We don’t know why this object was classified as sixth century or Byzantine, and we assume Gellatly bought it from an art dealer with that attribution.

The style of the artwork is perplexing. The closest examples we could find of similar Byzantine gold and glass artworks are The Castellani Brooch at the British Museum (late seventh – early ninth century) and The Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (early ninth century). Both are made with a technique called enameling – a process where powdered glass is fused to a metal substrate with high heat. This is a common technique for medieval metalworking, and what we would expect to see if our piece was Byzantine. But what we saw under the microscope was very different.

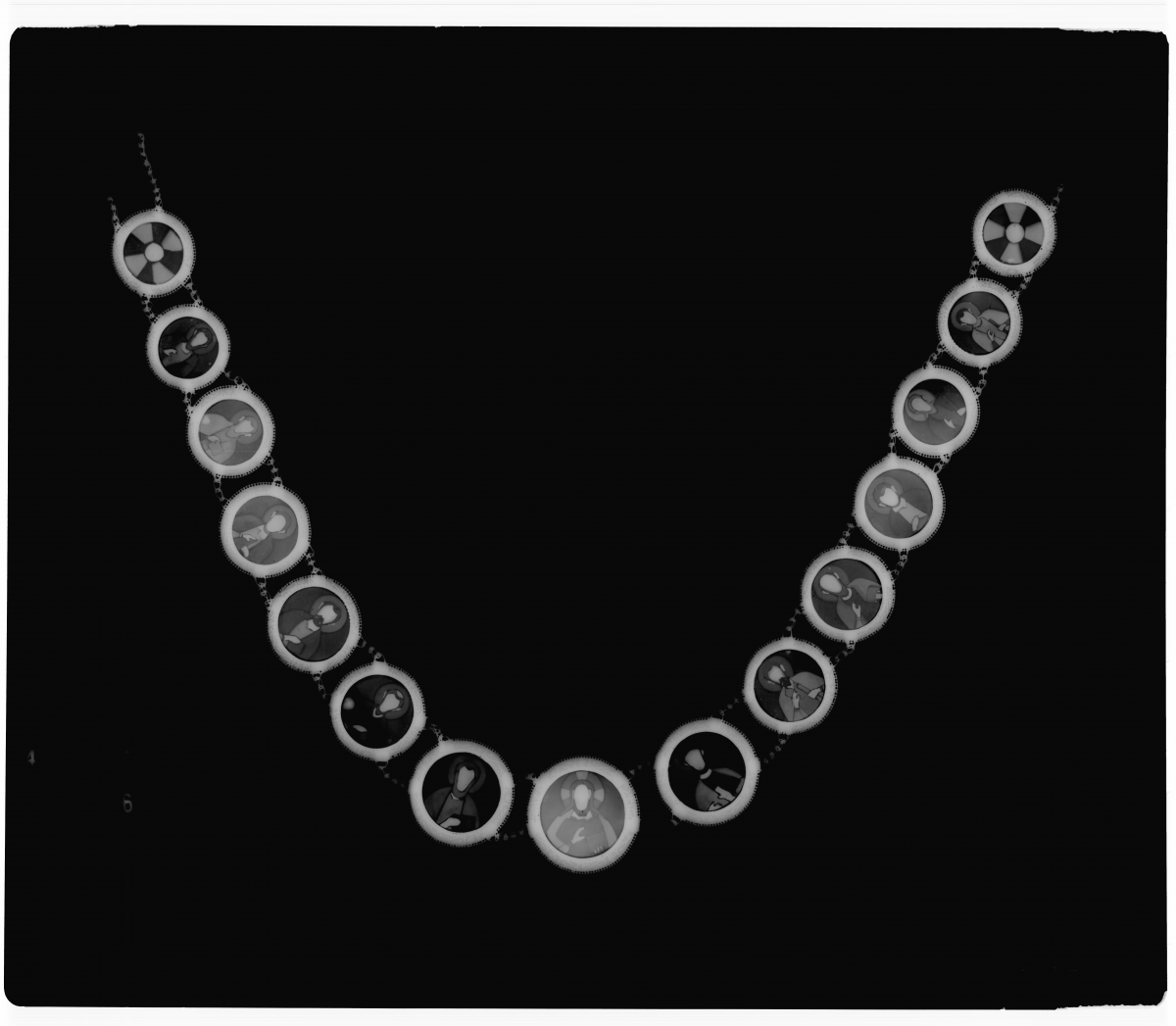

To study the materials, we examined the necklace in SAAM’s conservation labs. We looked at small details under a high-powered microscope, viewed and photographed the piece with ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) radiation, and x-rayed it.

The chains are made from flat sheets of gold, twisted and pulled through a drawplate to create hollow wire. This technique could have been used in both the ancient and modern worlds, but it is unusual unless you are trying to economize and save metal.

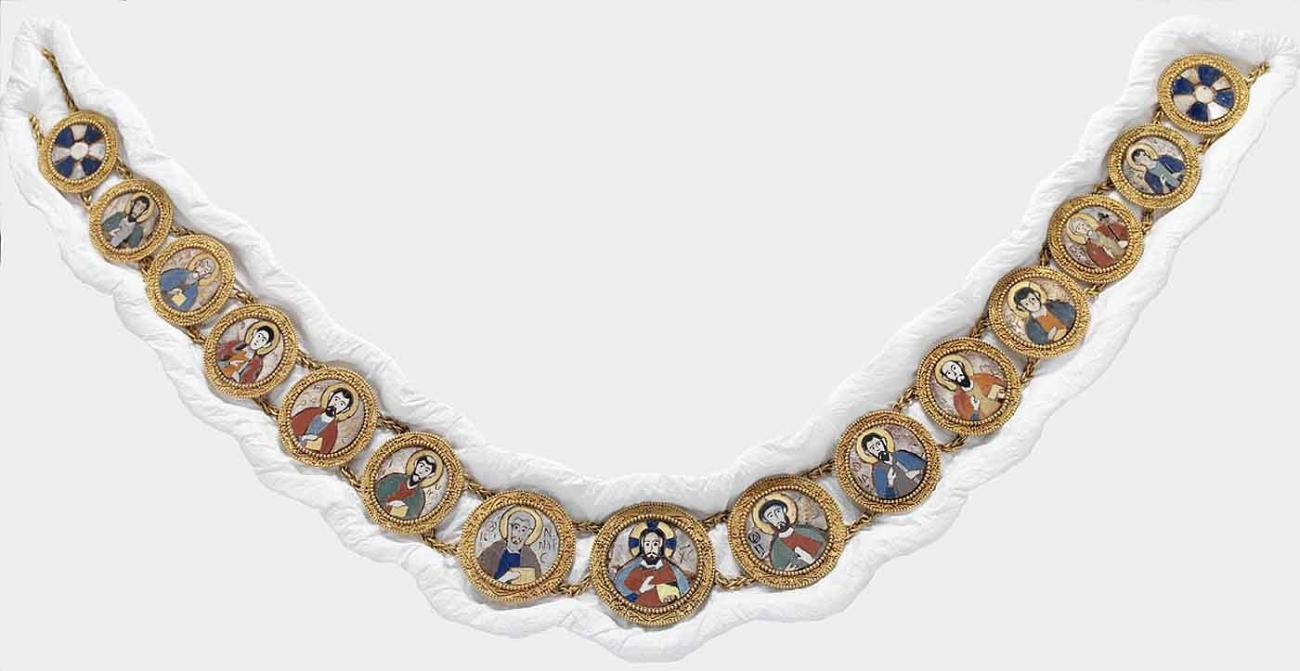

The base of the object is made of 15 gold medallions attached with gold chains. Each circular medallion was handmade from a gold sheet, hammered into a shape that resembles a shallow top hat. Each rim is decorated with hundreds of small gold balls, applied in a technique called granulation. Granulation was invented in the ancient world and prevalent with the Etruscans, but its popularity declined after the first century CE. Revived by the Castellani jewelry firm in the mid-19th century, granulation techniques could be made in the intervening centuries so nothing could be ruled out for our necklace. But it made us begin to question the Byzantine attribution.

Each gold medallion is inlaid with tiny pieces of glass and shell to depict thirteen half-length portraits of Christ and the twelve apostles, with Greek-style crosses at each end. At this small scale, glass inlays in jewelry are usually made with a technique called micromosaic – small rods of glass are cut and pushed into a backing material, building up the design with dots or ovals. But (are you sensing a theme yet?) not this necklace! The glass pieces are wide, flat, and intricately cut to fit together like puzzle pieces. The closest known technique is called pietre dure, where semiprecious hardstones are cut and fit together to create mosaics on intricate tabletops, walls, and even buildings. Pietre dure was known in the ancient and medieval Roman world, but was most prevalent in Florence, Italy from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries. Once again, this doesn’t rule anything out for our necklace. Are there any examples of pietre dure made in glass? If so, we haven’t found them yet.

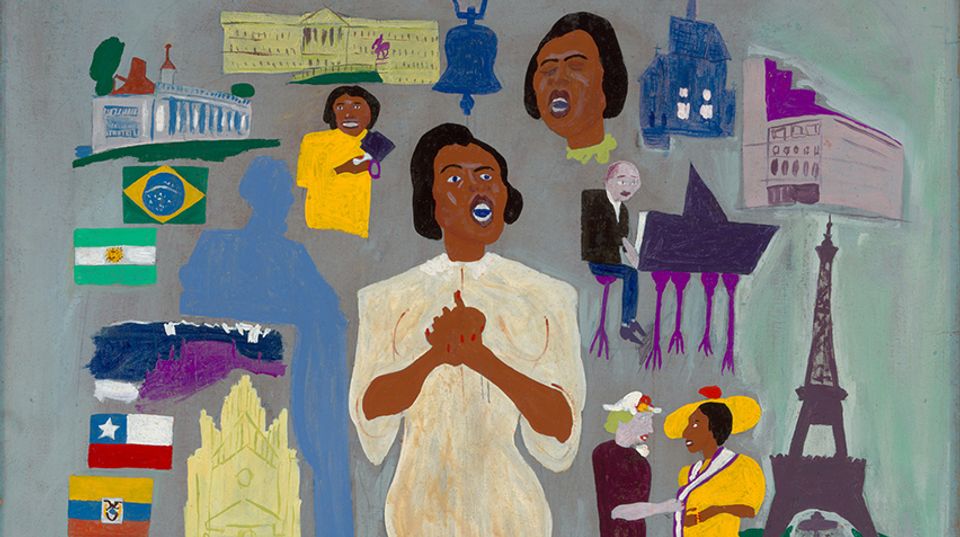

The glass inlay appears in a variety of bright colors: red, orange, yellow, green, light blue, dark blue, purple, and even gold leaf. But the glass used on one medallion stands out: the third figure on the left has a red robe with white, brown, and black spots. Made with several different canes of glass, the patterning of the robe resembles the decorative nineteenth century glassware patterns most associated with Venice. During the mid-nineteenth century, St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice was undergoing a major restoration of its famous glass wall mosaics. Could that project correspond with our necklace? If so, could the artist be sourcing glass from Venice, or working there, or both?

Our examination brought up more questions than answers: to get results, we can analyze the materials to narrow down our time period. The gold alloy might tell us if it was made pre- or post- industrial revolution. The glass composition could reveal a pigment or composition invented in the nineteenth century. Once the object comes off public view when the exhibition tour ends, we will have an opportunity to investigate these avenues.

This object has stumped every scholar who has looked at it. It doesn’t seem like a necklace that can be worn, and there aren’t similar Byzantine examples. Nineteenth-century archaeological revival jewelry is made with more precision, and we don’t see surviving ancient pieces made this way. The glass is cut in a way usually reserved for stone, and the iconography is depicted in an unusual way. Right now, we think the Venetian-style glass suggests a possible origin for the materials, maybe the object itself. Jokingly, we’ve said it was made by an itinerant nineteenth century Florentine pietre dure stone craftsperson who moved to Venice to restore the San Marco mosaics and was commissioned by a wealthy patron to make a Byzantine-style necklace. It sounds bizarre, but could it be true? Until we can analyze the materials further, these will remain as questions. It’s an extraordinary and truly unique object, and we hope someone reading this story might recognize something that will help us solve the mystery.