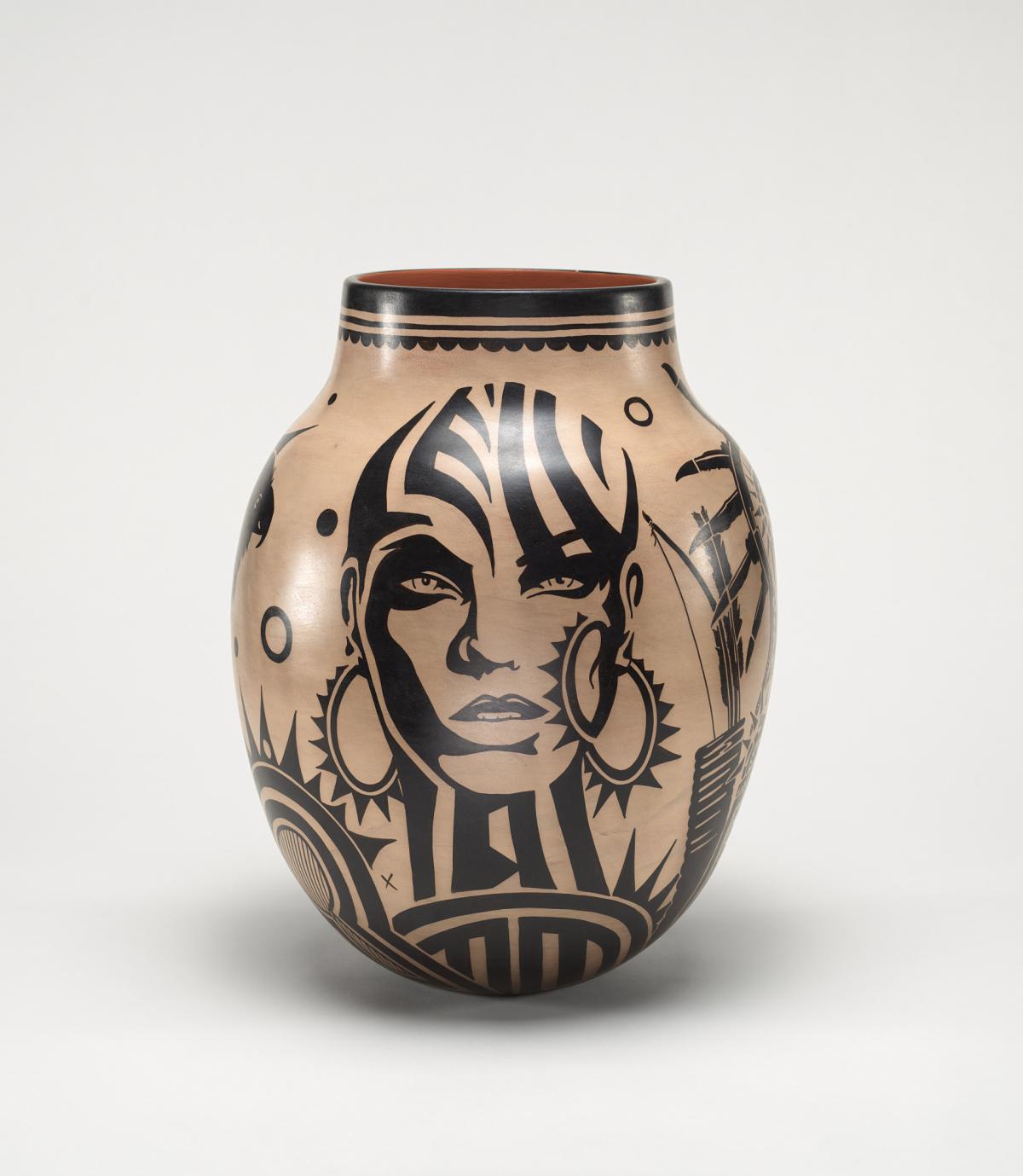

Virgil Ortiz (Cochiti Pueblo) is a storyteller whose artworks carry the history, traditions, and continued resilience of his Cochiti Pueblo people. Like generations before him, Ortiz gathers local clay, hand builds his vessels, and makes paint from wild spinach leaves, processes he learned from his mother, Seferina Ortiz. In describing his work as traditional, Ortiz explains, “... we hand dig all of our clay, all of our paints, every single material that we use to build this type of artwork. It's a dying art form right now, and I feel that I'm here to make sure that this art form does not die out.” For the imagery that adorns his work, Ortiz builds futuristic worlds and characters, where knowledge of the past provides guidance for future generations. Ortiz is represented in SAAM’s collection by Pueblo Revolt 2180.

Grounded in histories of Indigenous resistance and survival, the title of this artwork refers to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 when Pueblo people overthrew invading Spanish colonists in what is present-day New Mexico. This sculpture imagines the year 2180, when future Pueblo warriors defend their homelands again.

The uprising, recognized as the most successful revolt by Indigenous people against colonial powers in North America, was led by religious leader Po’pay (Tewa) to reclaim spiritual and cultural autonomy. The revolution, which began on August 10, expelled the Spanish from the region for 12 years and instilled in the Pueblo people a fierce commitment to cultural independence and preservation that continues today.

Ortiz describes the significance of the events. “It’s America’s first revolution, but nobody calls it that because of what happened to our people. So, I’m choosing to educate globally about the 1680 Pueblo revolt using artwork.”

Ortiz, in a recorded interview with SAAM staff, explains that he “...designed nineteen groups of characters that represent the nineteen Pueblos that are still left in New Mexico today.” Each side of the pot reveals different characters, including the Aeronauts, the Translator, and the Blind Archer Leader, Da’u. The female warrior Tahu, with her quiver and arrows on her back, leads the army. She is accompanied by figures such as Gliders, running messages across pueblos, and Translator, the army commander, communicating the events across time. Ortiz goes on to say that he “...chose to tell the story, our history, to have the world acknowledge that we're still here and what happened to our people...” with the hopes that the design and storytelling styles of the pot will appeal to a younger generation.

This story is drawn from texts and interpretive materials created for the exhibitions The Shape of Power: Stories of Race and American Sculpture and This Present Moment: Crafting a Better World. To learn more about Ortiz and his work, listen to his recorded keynote at SAAM’s Renwick Gallery in 2023.