The Renwick Gallery is home to the Smithsonian American Art Museum's program of contemporary craft and decorative arts. The Renwick building, a National Historic Landmark, is the first built expressly as an art museum in the United States, and is considered one of the first and finest examples of Second Empire architecture in America. It is located steps from the White House in the heart of historic federal Washington. The building underwent a major renovation from 2013 to 2015.

Discover SAAM's Renwick Gallery

“To Encourage American Genius”

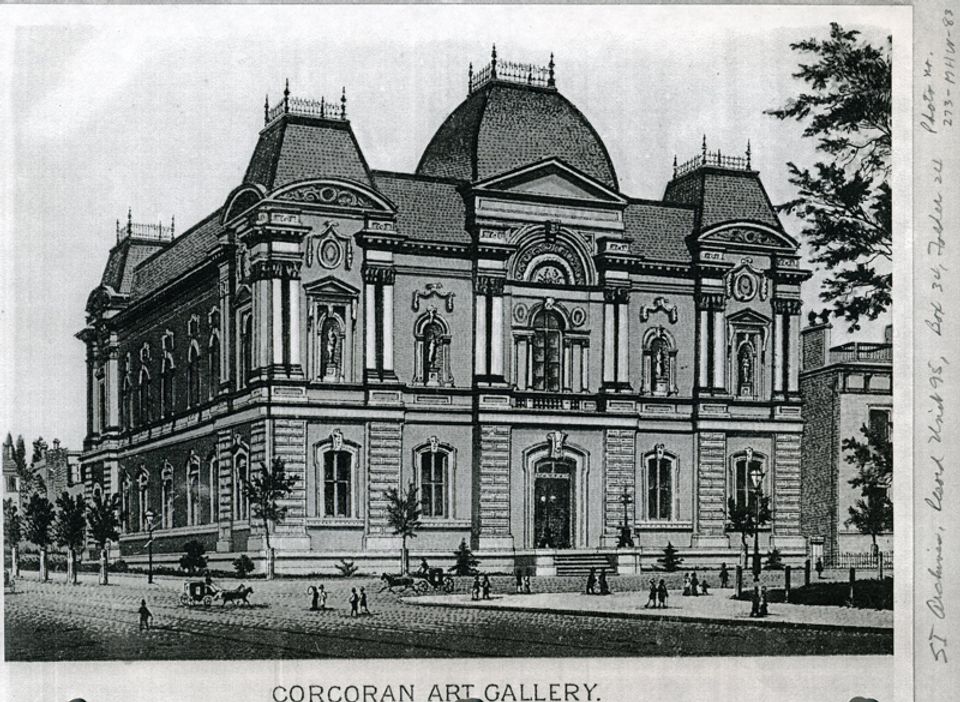

The building now known as the Renwick Gallery was originally designed to house the art collection of William Wilson Corcoran, a nineteenth-century native of Washington and a prominent banker, philanthropist, and art collector. Corcoran felt passionately that the fledgling United States needed distinct achievements in the realm of arts and culture, as much as in industry and trade, if it was to become one of the great nations of the world. Showcasing works by American artists to the public would, he believed, “encourage American genius” and demonstrate that American art could rival that of Europe. In 1858 Corcoran engaged the noted architect James Renwick Jr., who had earlier designed the Smithsonian’s Castle in Washington and St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, to design a public museum in which to display his collection of American art.

An American Louvre

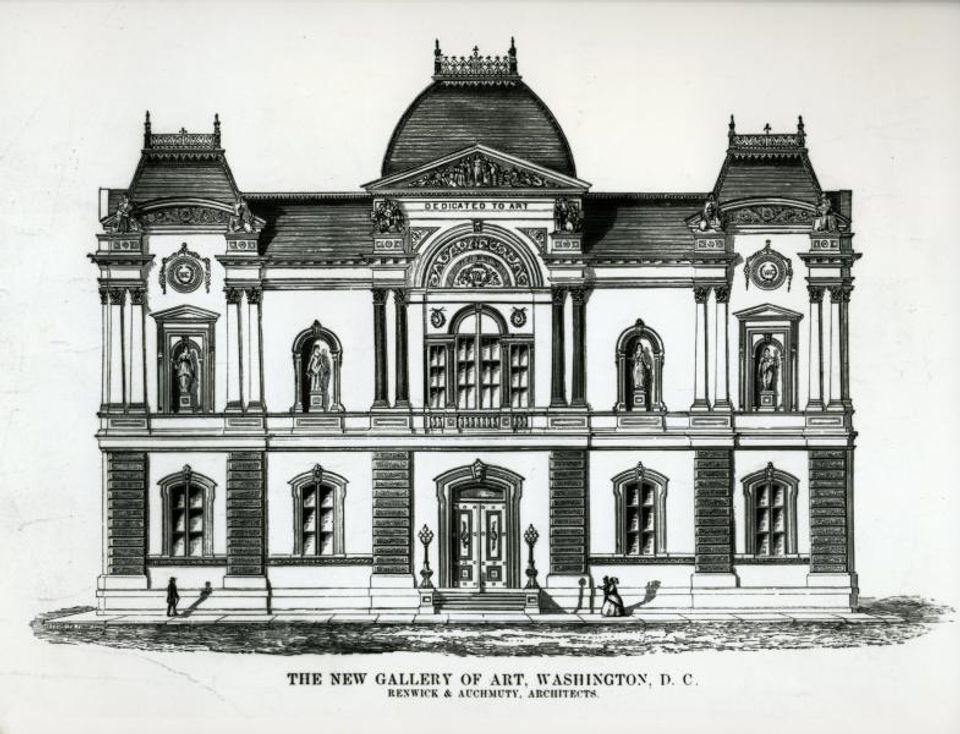

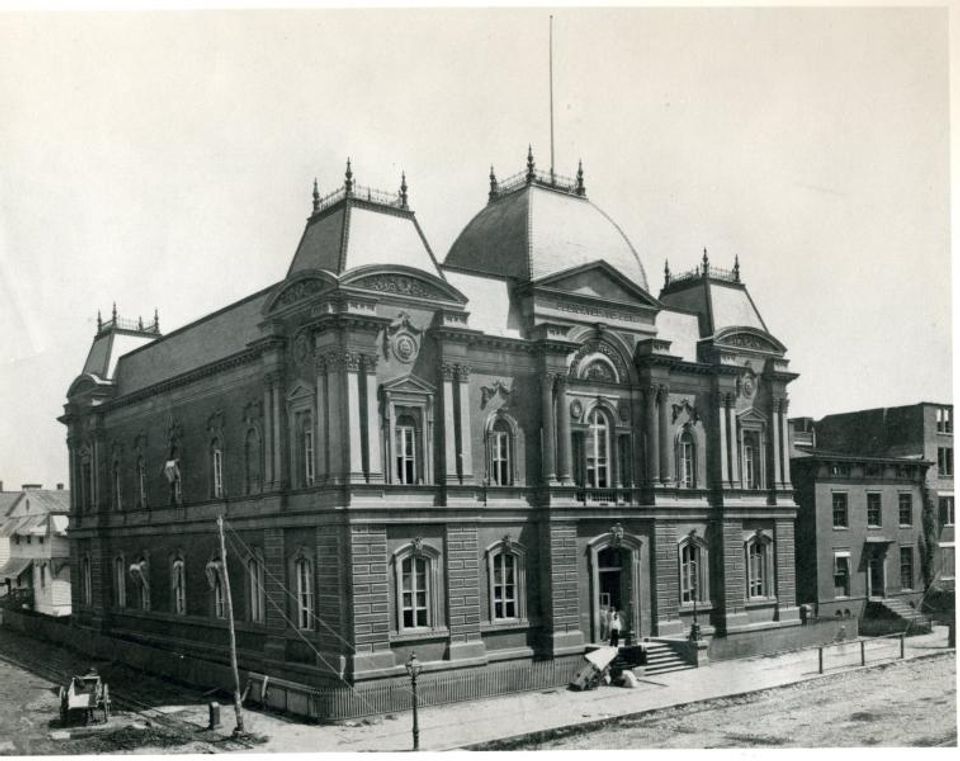

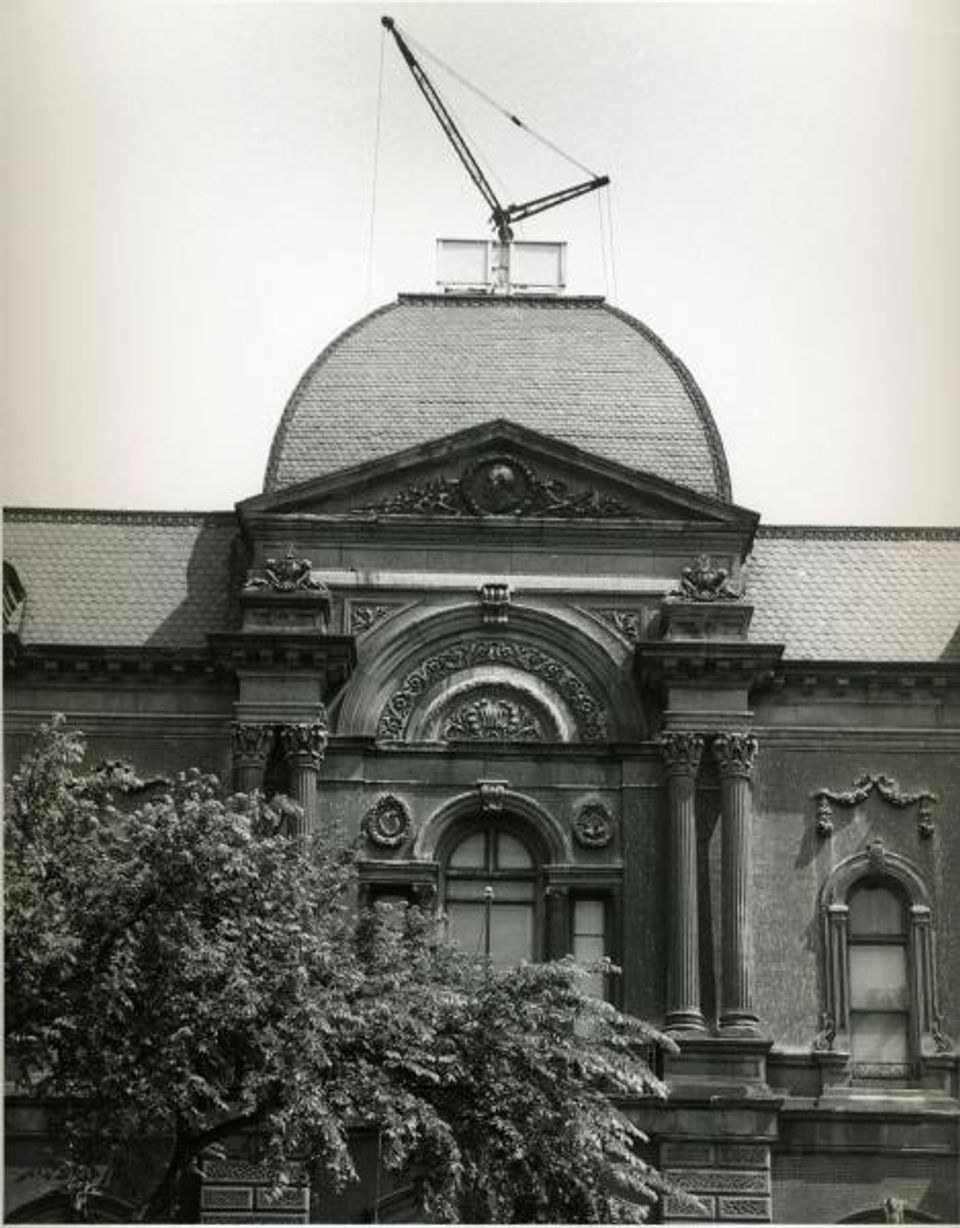

The construction of the Renwick building marked an important moment in the cultural history of the United States, as it was the first time a building had been designed expressly as an art museum, and helped to introduce a new style of architecture to Washington and to the nation.

Renwick was inspired by the Louvre’s newest addition in Paris and modeled the gallery in the Second Empire style that was then the height of French fashion. His design integrated the pavilions, mansard roofs and double columns that he saw in France with his own creative interpretation of proportions, details and architectural elements. The words “Dedicated to Art” were inscribed in stone above the front entrance. The result was a building unlike anything else in the United States at the time, popularizing a style that soon spread throughout the country. Upon its completion following the Civil War, Senator Charles Sumner and The Philadelphia Bulletin dubbed the building “The American Louvre,” and the museum helped to establish Washington as a cultural center.

Jackie Kennedy and Historic Preservation in Washington

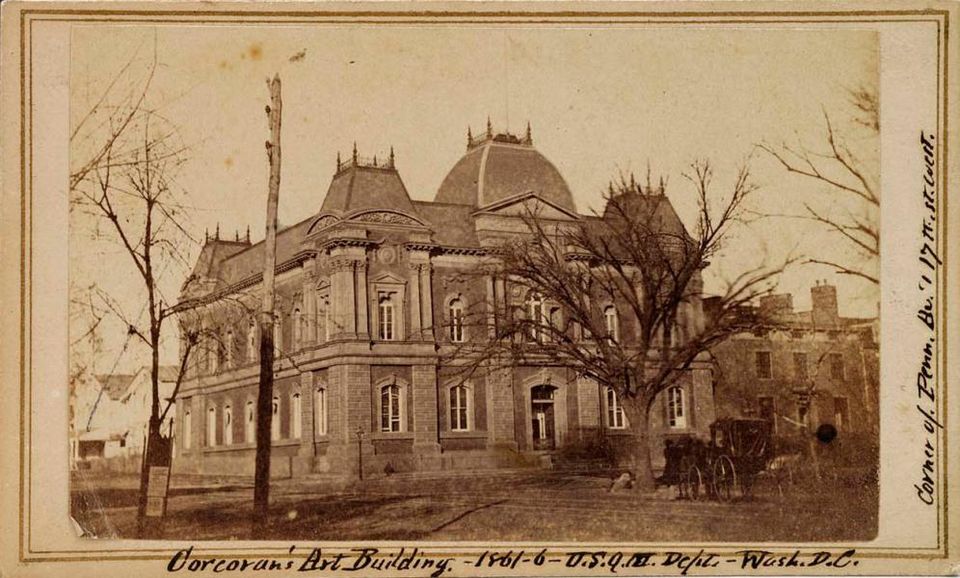

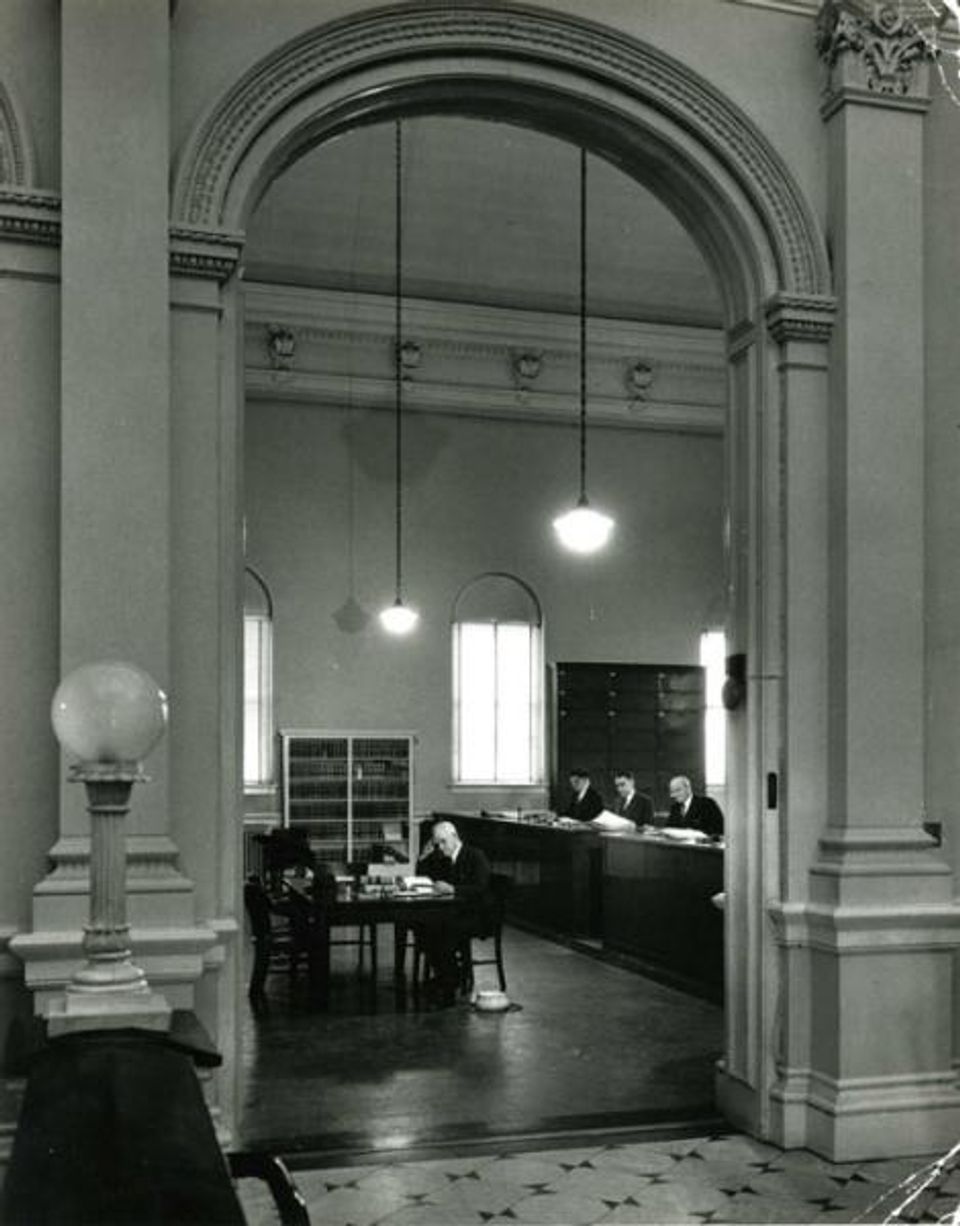

The U.S. Court of Claims took over the building in 1899, after Corcoran's collection had been relocated to a larger building. In the 1950s Congress proposed that the increasingly-dilapidated building be razed as part of its plan to construct new, larger government buildings. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy successfully led the campaign in 1962 to save the Renwick Gallery as part of her plan to restore Lafayette Square and to preserve its historic treasures.

In one of her letters on the subject of the Renwick building she wrote, “It may look like a Victorian horror, but it is really quite a lovely and precious example of the period of architecture which is fast disappearing. I so strongly feel that the White House should give the example in preserving our nation’s past.” She went on to propose alternative uses for the building, including as a museum; plans for the demolition of the Renwick building were eventually halted, due largely to her efforts.

1965, S. Dillon Ripley, then secretary of the Smithsonian, met with President Lyndon B. Johnson to request that the gallery be turned over to the Smithsonian. The Renwick Gallery opened January 28, 1972 as the home of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s contemporary craft program and was named in honor of its architect.

The Renwick of Yesterday

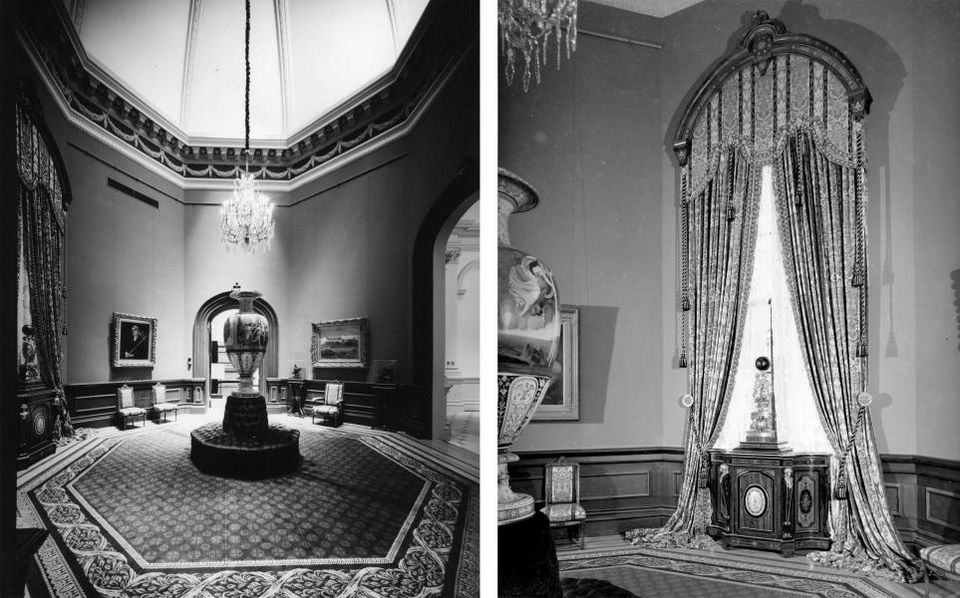

When the Renwick Gallery opened its doors almost half a century ago, it was a product of its time, reflecting a then-contemporary excitement for the handmade that had reached fever pitch. Its brick-and-mortar home could not have been better suited to the character of the movement: a historic structure that had fallen out of favor, brought back to life and made modern. A gem of a museum, it was small enough to take in in a single visit but grand in stature and architectural detail, and filled with remarkable and unexpected treasures. And though it was off the beaten path for most museumgoers in the city, who would cram into the National Mall to see attractions such as the Hope Diamond, the 1903 Wright Flyer, and Dorothy’s Ruby Slippers, it quickly grew a small but dedicated following. In its airy halls, kitty-corner to the White House, one could find space and time and quiet to roam, taking in the marvelous if lesser-known objects inside, all collected under the name of ‘craft.’

Historic Renwick Gallery Architecture

It would be no exaggeration to say that the founding of the Renwick Gallery in 1972 was among the crowning achievements of the Studio Craft movement. Throughout the country, momentum had been steadily growing around craft since the end of World War II, and by the late 1960s, craft fairs dotted the landscape, craft schools and university programs were numerous and thriving, and disparate communities, brought together by the American Craft Council and magazines like its associated Craft Horizons, felt united like never before. The communal, counterculture spirit of the ‘60s served to bolster the movement, and these developments led to simultaneous renaissances in all manner of practices from glass blowing to wood turning to wheel throwing, from blacksmithing to basket weaving. But while interest in the crafts had never been higher, there were only a handful of small exhibitions and even fewer museums devoted to the subject.

Then in 1969, the landmark exhibition Objects USA began its international tour at the National Collection of Fine Arts, (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum) causing a stir and setting the scene for the Renwick’s entry into the Smithsonian family. A joint venture of the S. C. Johnson and Son Company and curator Lee Nordess, Objects USA sought to raise the status of the craft to the realm of fine art, and it largely succeeded in doing so. Visitors flocked to the show to see handmade household objects from chairs to chafing dishes, some functional and some shockingly dysfunctional, which the museum displayed in room-like scenes and elevated to distinction within the galleries.

At last, despite craft’s longstanding angst that it would disappear in the wake of industry, it was instead welcomed as its cure: a warm companion to mechanical production, adding a human element, wit and charm, to the otherwise cold, manufactured ‘world of tomorrow’ that was mid-twentieth century America. And so when the majestic building was donated to the Smithsonian Institution, a young Smithsonian director, Lloyd Herman, seized upon the opportunity and presented the idea that this building might house the nation’s first collection devoted to the crafts. To his surprise, his proposal was accepted. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Under Herman’s direction, medium-based exhibitions like Woodenworks (1972), solo shows like Baskets and Cylinders: Recent Glass by Dale Chihuly (1978), and wide ranging surveys like Craft Multiples (1975) and The Object as Poet (1976) broke ground in highlighting extraordinary craftsmanship by largely under-recognized artists who were rising to prominence. These defined the early character of the Renwick and solidified its importance in the craft conversation, also playing a significant role in the careers of notable artists such as Albert Paley, Dale Chihuly, Sam Maloof, Maria Martinez, Anni Albers, and many others. While it took some time for the Renwick to settle into its identity and find its voice (it began as a kunsthalle, exhibiting international craft and design of all kinds, and did not focus on American work and begin collecting until 1975), the remarkable opportunity to collect history as it was happening proved too enticing to pass up.

The Renwick of Today and Tomorrow

Today, the Renwick’s collection has grown to encompass nearly 2,000 objects, and it is considered one of the finest and most extensive representations in the world of this vibrant and uniquely American movement. As Studio Craft gradually transitions from the contemporary into the historical, the Renwick continues to honor the pioneers of the field, even as it has begun to document the fertile years following the movement, bringing to light a new generation of makers who are both preserving and transforming those traditions for the future.

Craft continues to thrive not because it has aligned itself with any particular practice, but because it offers an alternative way of interacting with our environment, an ideology of living differently in the modern world. Although for a generation craft has been defined by a list of five traditional media—wood, fiber, metal, glass, ceramic—these categories have functioned as shorthand at best. Craft has never really been about medium, but rather about what those medium-based practices represent: the very skill, individuality, community, and tradition that make it so captivating to marketing campaigns. In short, what holds craft apart and gives it its meaning in the machine age—both to makers and consumers alike—is that it remains unabashedly human, like us. It is from this turbulent landscape that a new wave of craft artists asserting its own voice. Largely rooted in a populist revival of the crafts and responding to the rapidly changing world around them, and their activist values, optimism, and entrepreneurial spirit in some way echo the pioneers of the American Studio Craft Movement in their heyday—drawing on the ideological, communal spirit that has always accompanied craft—and their coming of age feels like the rebirth and reinvigoration of a cycle. At the same time, the work of these young artists embodies something fresh and completely new, with contemporary values. Coming of age in the internet era, they are untethered by medium-based definitions and easily navigate between physical and virtual worlds, undaunted by technology. They intuit craft’s importance as a nuanced visual language, based on process, materiality, and the tradition of the handmade. And as technology continues to evolve, they are poised to grow with it, helping us interpret the world around us while creating the extraordinary objects of tomorrow.