Artist

David Beck

born Muncie, IN 1953-died San Francisco, CA 2018

- Also known as

- David Beck

- Born

- Muncie, Indiana, United States

- Died

- San Francisco, California, United States

- Active in

- San Francisco, California, United States

- New York, New York, United States

- Biography

- David Beck is influenced by crank toys, whirligigs, and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century mechanical robots called automata that delighted, and sometimes tricked, children and adults. An accomplished woodworker, sculptor, painter and craftsman, Beck builds intricate moving sculptures such as operas, band shells, movie houses, and museums. Beck handcrafts each complex component himself using rare materials such as linden and walnut woods, ivories, inlays, lacquers, and mussel and ostrich-egg shells. He is a musician as well as an artist and records many of the sound effects for his pieces.

Videos

Exhibitions

October 30, 2014–February 22, 2015

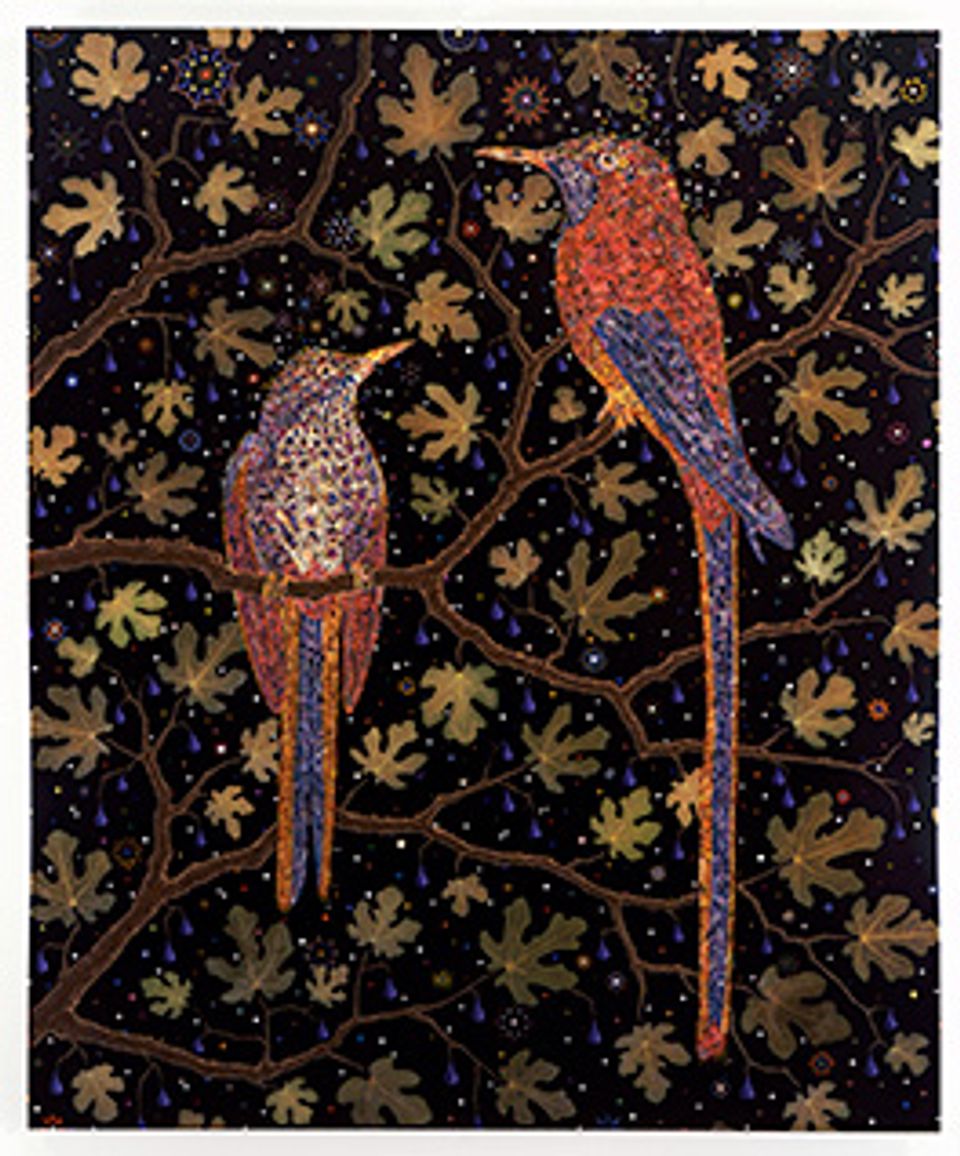

Birds have long been a source of mystery and awe. Today, a growing desire to meaningfully connect with the natural world has fostered a resurgence of popular interest in the winged creatures that surround us daily.