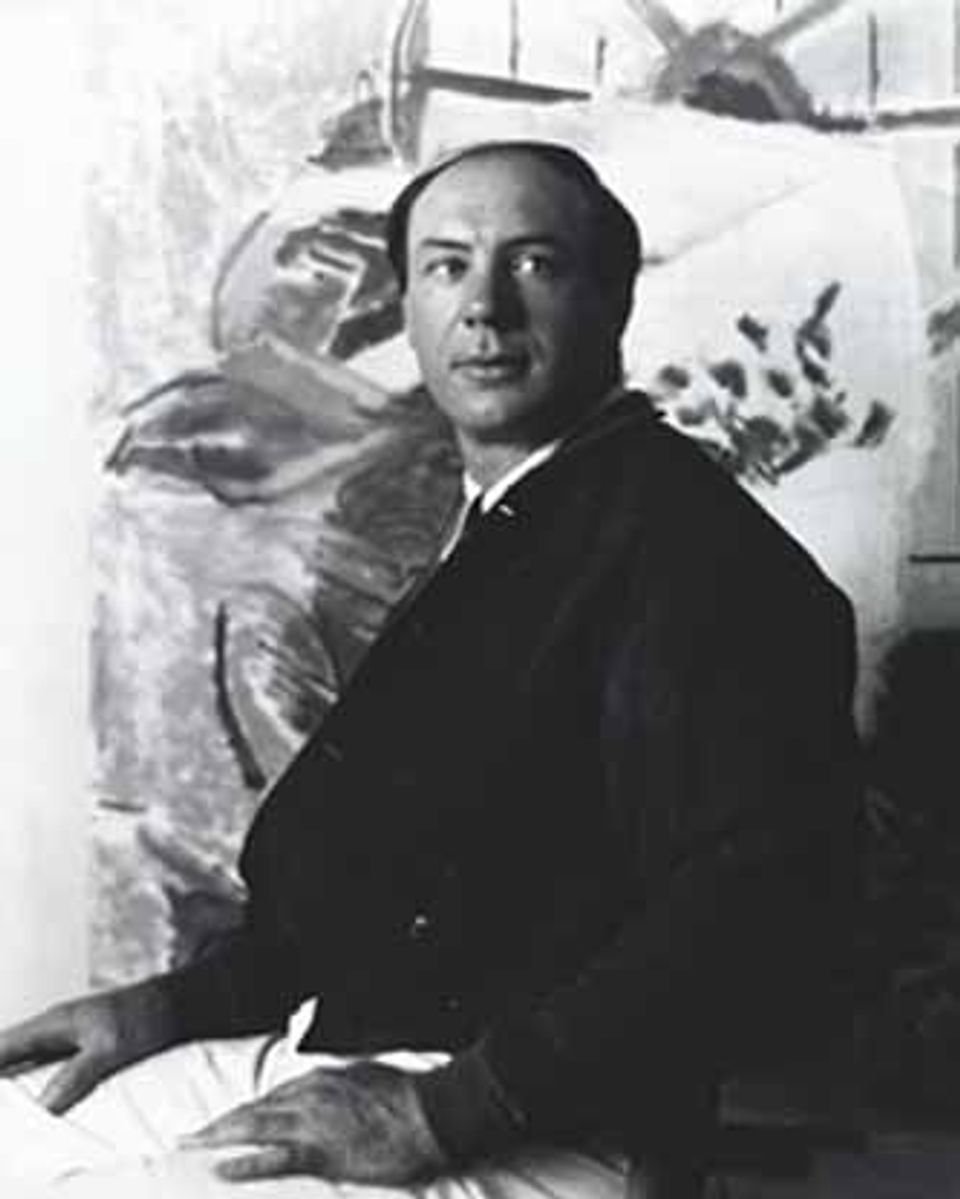

Karl Knaths

- Also known as

- Otto Karl Knaths

- Born

- Eau Claire, Wisconsin, United States

- Died

- Hyannis, Massachusetts, United States

- Active in

- Provincetown, Massachusetts, United States

- Biography

Painter. Knaths applied his system of color theory to his abstract landscapes and scenic depictions, which were highly Cubist in style. He was a favorite of patron Duncan Phillips (Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.), who purchased the first painting that Knaths sold (1926) as well as many subsequent works.

Joan Stahl American Artists in Photographic Portraits from the Peter A. Juley & Son Collection (Washington, D.C. and Mineola, New York: National Museum of American Art and Dover Publications, Inc., 1995)

- Artist Biography

Karl Knaths, who lived in Provincetown, Massachusetts, from 1919 until his death in 1971, was one of the first Americans whose work found its way into Albert Gallatin's Gallery of Living Art. By virtue of his residence away from New York, Knaths was never an active member of the American Abstract Artists. Nevertheless, his affiliation brought distinction to the group. Knaths was older than many of the group's members, and exhibited in New York to generally positive reviews from about 1930 on (although he once remarked that except for Duncan Phillips's annual purchase, he did not sell a single painting for twenty-three years).(1) Recognized as an important modernist, he had the valuable support of Duncan Phillips. Over the years Phillips bought many of Knath's paintings and frequently invited him to lecture at the Phillips Collection in Washington. In October 1945, Knaths exhibited in a group show at the Paul Rosenberg Gallery. The following January, he had the first of twenty-two solo exhibitions—almost one each year—until his death twenty-five years later.

Originally from Eau Claire, Wisconsin, in 1912 Knaths entered the school of the Art Institute of Chicago where he remained for five years. From there he went to New York, and later settled in Provincetown. In 1922, three years after his move to Cape Cod, he married Helen Weinrich, a pianist, whose sister Agnes was a Paris-trained abstract painter, and built the house that would be his home for the remainder of his life. During the winters, the Knaths and Weinrich usually spent a month in New York; but Europe, which attracted so many of Knaths, colleagues, failed to lure him from his beloved Provincetown.

Yet, in his lecture notes, and in a manuscript for an unpublished book entitled Ornament and Glory, Knaths, thorough understanding of modernist tenets as well as the principles of Renaissance and subsequent European art is apparent.(2) His papers contain typescripts of Hans Hofmann's lectures and writings by Mondrian, Malevich, Kandinsky, and other important theorists of modernism. Yet of all the artists whose work he knew well, the strongest parallels to Knaths, work come with Céanne's late paintings. Both artists blended an intuitional understanding of structure with motifs drawn from observed nature. For his subject matter, Knaths drew repeatedly from his Provincetown surroundings: deer in landscape settings, clamdiggers returning from work, fishing shacks, boats in the harbor, still lifes of duck decoys and fishing paraphernalia. But Knaths also found inspiration in American folklore and literature, and did paintings of Johnny Appleseed, Paul Bunyan, and Herman Melville's Ahab.

Knaths was one of the most theoretically inclined painters of his generation. He agreed with Kandinsky that "there are definite, measurable correspondences between sound in music and color and space in painting: specifically, between musical intervals and color intervals and spatial proportions."(3) Knaths worked out intricate charts for color and musical ratios,which he used to determine directional lines and proportions in his paintings. Like Hofmann, he believed that "whatever is to be realized by the painting should arise through the use of pictorial elements in a thematic way. The surface being the prime element, it is possible to manipulate full spaciousness within its flat terms …"(4)

At some point, Knaths discovered Wilhelm Ostwald's color system. Based on color and not on light, the Ostwald system was devised as a way of ordering color, and was quite popular among American artists of the time. Knaths not only used this system, he harnessed it to a complex set of mathematical and geometrical relations—akin to musical proportions—so that the theoretical foundations of his art were both complex and highly worked out.

In his paintings, whether sketchy, experimental works like the Untitled gouache, circa 1939–40, or in more highly ordered canvases, Knaths remained true to the artistic principles he began to develop early in his life.

1. Paul Richard, "Conflict of Colors: Karl Knaths at the Phillips Collection," The Washington Post, 11 September 1982, C-1.

2. An edited transcription of Knaths, Ornament and Glory that includes facsimile reproductions of about half the manuscript pages was published in Jean and Jim Young, Ornament and Glory: Theme and Theory in the Work of Karl Knaths (Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Edith C. Blum Art Institute, Milton and Sally Avery Center for the Arts, The Bard College Center, 1982).

3. Lloyd Goodrich, Karl Knaths (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1959).

4. Karl Knaths, "The Problem of a Painter," Ornament and Glory, p. 35.

Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)