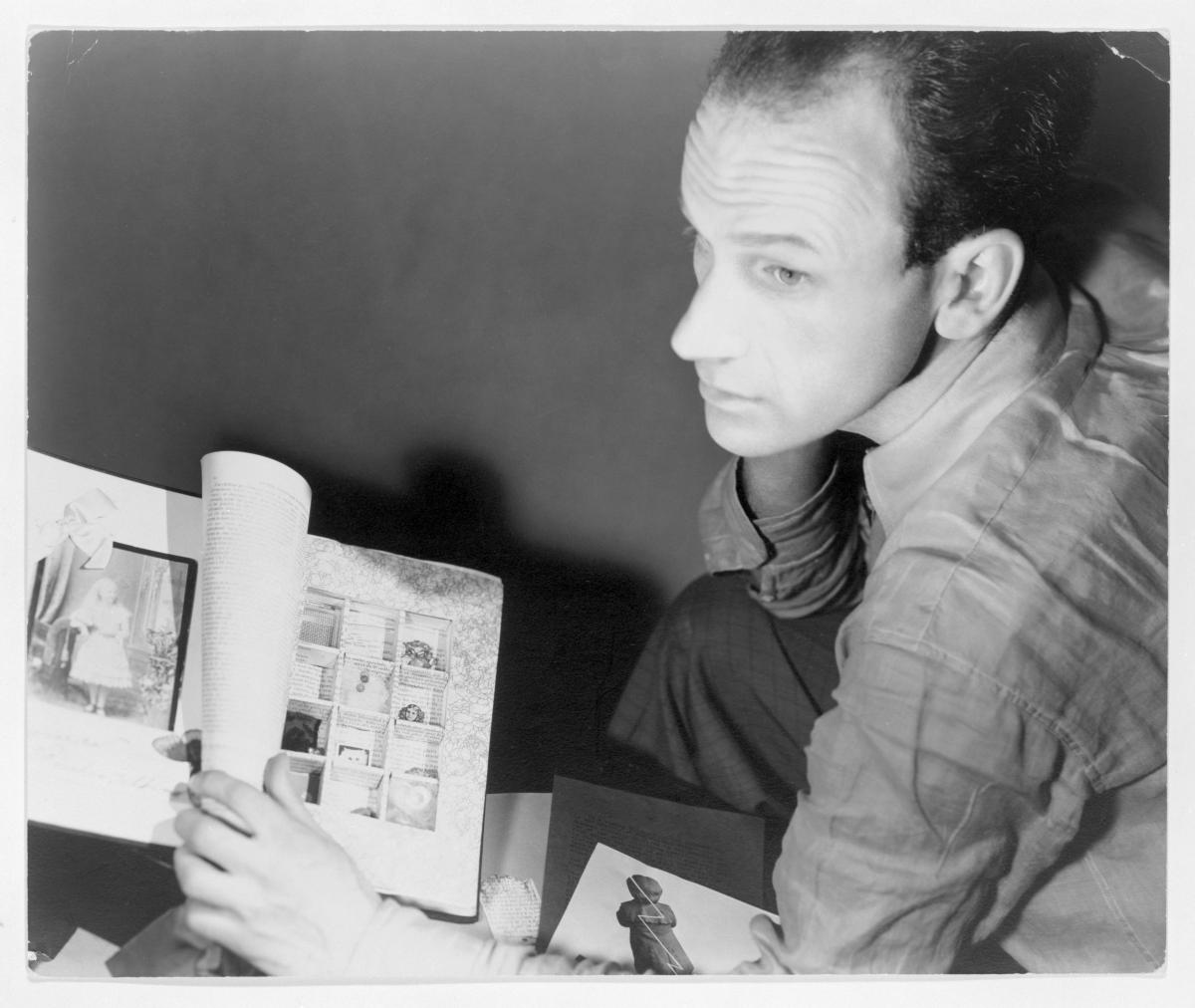

In the summer of 2017, I began work as the archivist of the Joseph Cornell Study Center collection in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). My task, to put it simply, was to arrange, describe, and make accessible a room full of the studio contents, personal and family papers, and library and record collection of collage artist and avant-garde filmmaker Joseph Cornell (1903-1972).

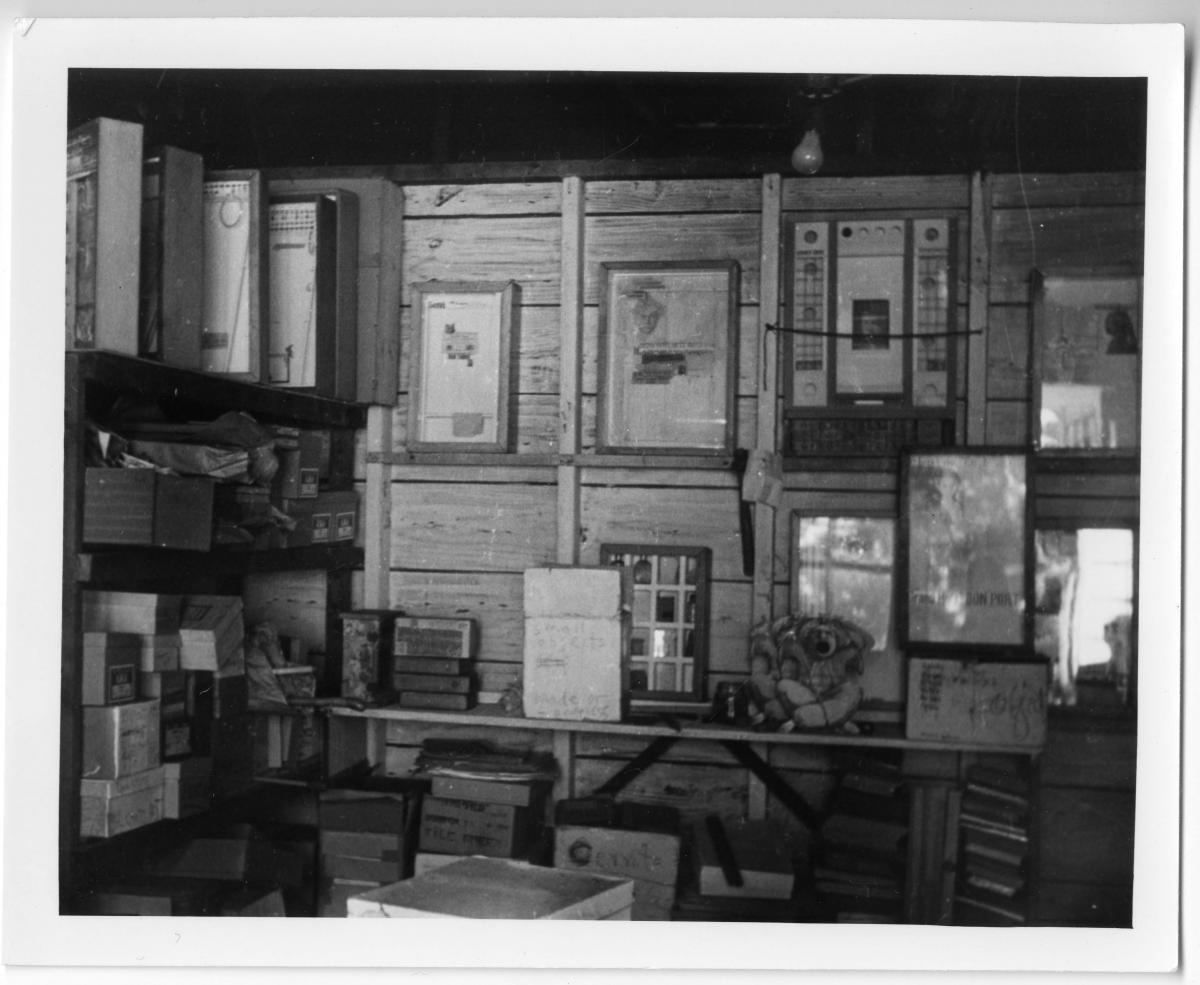

Working primarily from his basement studio at home in Queens, New York – a home that he shared with his mother and brother for their whole lives – he collected a wide range of materials that he would store in cardboard boxes or cigar boxes. Images clipped from magazines, articles from newspapers, and scattered notes often resided in overstuffed folders or in stacks along various surfaces of his studio.

My first task was to familiarize myself with the history of the collection and how it came to be at SAAM—no small task, since the collection began with a donation from Joseph Cornell's sister, Elizabeth Cornell Benton, in 1978, along with several additional donations and transfers of personal materials into the 1990s. A veritable treasure trove of material giving insights and contextual clues to Joseph Cornell's work and life, the collection has been available to visiting researchers and previously included in comprehensive exhibitions and publications on the artist. But access was previously limited by the extreme extent and variety of the materials and the lack of a complete finding aid (an organizational document providing description of contents and contextual information) to the collection.

The next step was to familiarize myself with the physical materials, the extent of groups or types of material, and determine if the creator of the collection, Joseph Cornell, had any organizational systems in place and maintain those systems. I also needed to determine if there were any conservation or preservation concerns, which ultimately required going through all of the items in the collection to make a preliminary assessment.

As most gatherers of things are aware, materials kept in basements and attics where temperatures and humidity tend to fluctuate, are often more at risk for mold, rust, and pests. Since the collection has been in a climate-controlled space for upwards of 40 years, any discovered damage was likely due to the materials themselves degrading. For example, archivists are generally averse to keeping old paper clips in collections because these tend to rust and damage paper, and this was no exception for this collection. Also, in a collection like this it is not unusual to discover unstable film and paper materials, such as old newspapers and newsprint or nitrate and acetate film negatives.

Acetate film negatives were introduced in the 1930s and the popular film negative used until the more stable polyester film was introduced in circa 1960. Acetate negatives, after a number of years and depending on their storage conditions, can break down and off-gas, becoming a risk to materials stored near them, and negatives can warp and wrinkle, rendering the image inaccessible. Newspaper, inherently unstable and acidic, becomes brittle over time. These materials need special housing considerations and take more measured and planned approaches as other processing and arrangement work continues. The extent of this type of material, material that needed more attention and care, turned out to be much more than originally anticipated, causing me to necessarily adjust workflows and timelines.

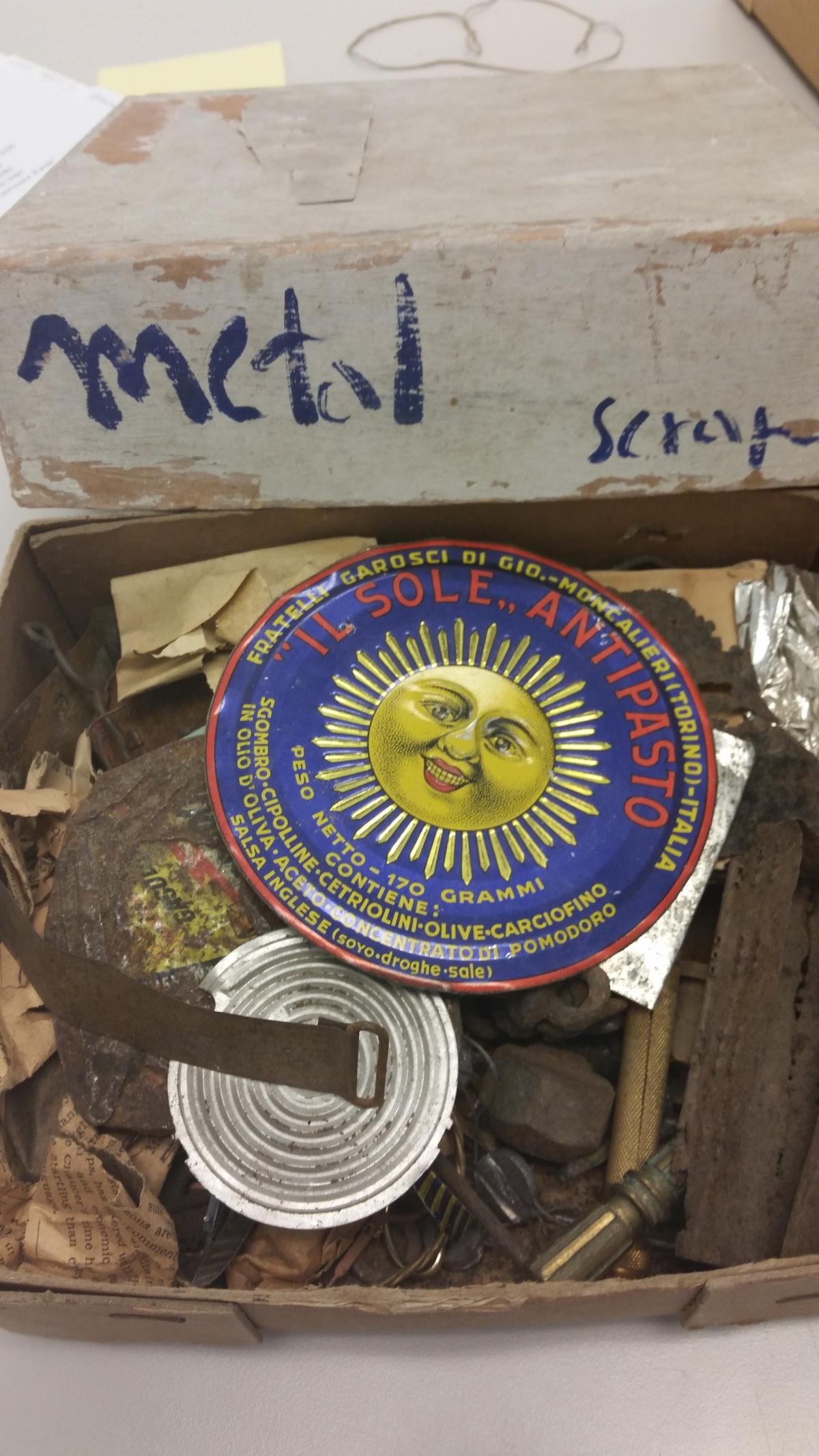

But my work hasn't been all rusty paperclips and brittle pages. One of the most interesting aspects of Joseph Cornell's life has been how nostalgic he appeared to be about so many things. He might be having a good day, taking a walk, and find a rusty bit of metal or a pull tab from a soda can. He would pick up that found bit and attempt to capture that good day by scrawling a little note, or a date and a word, and fold it around that bit of metal. These were the constant surprises of the collection, in addition to whimsically labeled boxes of other stuff—"Mouse Material" being one of my favorites. Much to my relief, this box doesn't actually contain mouse fur, but what appears to be gathered dust or lint from a vacuum.

While working through what amounts to Joseph Cornell's life and a kind of fractured story of his artwork and ideas, there's a certain urge to create groups of material based on known works of art. This urge simply comes from wanting to understand Cornell's mind and present a body of material that makes sense to outside eyes. However, the work of an archivist is not to contrive groups of material or force things to fit into our need for order, it is to understand the original intent behind a stack of paper, given contextual clues, folder titles, or material type. With Cornell, the complexity of a found objects artist combined with an individual who nostalgically collected and gathered so much, this work was often like untangling an especially knotted bundle of chain jewelry. For me, this meant that I never decided a group of material was about any one thing unless explicitly stated through labels and notes by Cornell himself. Oftentimes, a group of material was about more than one thing, idea, person, memory, etc.

Understanding this, my next step, apart from reading extensively about Joseph Cornell, was to come up with a planned arrangement for the collection. With a collection numbering hundreds of boxes, a planned outline is necessary to make the work doable. Having gone through the collection and available inventories, I could estimate which boxes would include which kind of material, according to my arrangement, and approach the collection work in this way. Of course, with all great plans comes the possibility for adjustments along the way, and that is part of the work as well. Having tackled the overall high-level approach to the collection, I then spent the next several years working through each item—unfolding notes, removing paper clips and staples, removing materials from envelopes, interleaving acidic documents with archival paper to extend the life of the material, and properly housing everything in new, acid-free and lignin-free folders and boxes. I began with the paper-based documents, which made up a large part of the collection. My approach was to think of the collection as large groups of material: with the paper-based materials as one group, including photographs, prints, magazines, letters, financial records diaries, etc.; the three-dimensional objects that require special housing considerations and a different approach, as another part of the collection; the library collection of hundreds of boxed books with notes and annotations, as another part; and the record album collection as another part. Each of these larger groups has been described in the same comprehensive finding aid to the collection, but housing and planned physical approach differs for each type of material.

Going forward, further work can be done to physically get the collection to where it needs to be, but the collection now has a publicly accessible, comprehensive description in the form of the finding aid, which is a big step towards accessibility and findability of such a significant, unique collection of an important American artist.

To learn more about the Joseph Cornell Study Center collection at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, please visit https://americanart.si.edu/research/cornell

To view the finding aid to the collection, please visit https://sova.si.edu/record/SAAM.JCSC.1

Anna Rimel is the former archivist of the Joseph Cornell Study Center. This story originally appeared on the Smithsonian Collections blog on June 21, 2021. Take a closer look at Joseph Cornell's work and his continuing influence on SAAM's Stories.