Augusta Savage (1892–1962), Gamin, 1929, painted plaster, 9 x 5 3/4 x 4 3/8 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Benjamin and Olya Margolin, 1988.57

Student Questions

1. How would you describe the boy depicted in this sculpture? What can you deduce from his clothing and facial expression?

2. What textures do you notice? What do they contribute to the character of the figure?

3. Can you find the artwork title carved into the bust? (Enlarge the picture if needed.) Do you know what that word means?

About This Artwork

Augusta Savage used a classical sculptural form, a portrait bust, to portray an impoverished subject, a gamin, the French word for a boy who lives on city streets. He peers from beneath a cap, cocked to the side, which frames his soft, full cheeks and his large eyes. This reveals an engaging expression, which Savage emphasized by arching his neck slightly and tilting his head so that his face and eyes open upward to meet the viewer. Savage retained her hand and tool marks on the plaster's surface, textures that lend the boy an approachable, informal air. Nonetheless, Savage painted the surface a dark color and gave it a shiny finish, making it look like expensive bronze.

The balance Gamin strikes between its classical form and the subject's casual demeanor won Savage much praise. Indeed, the bust helped propel the sculptor's career, which despite some notable success had seen upsetting setbacks, many due to racism. For example, although she had been commissioned to make portraits of notable African American leaders, like W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey, she was denied a fellowship to study in France due to her race. Gamin changed her fortunes. It appeared on the cover of Crisis magazine in 1929 and increased her recognition as a leading African American artist. The work also brought her to the attention of the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which awarded her a Rosenwald Fellowship. This award, along with money donated by African American organizations, enabled Savage to study art in Paris for two years.

Savage's Gamin was also notable because it gave respect to her subject: a poor African American child. Throughout history, formal busts have typically been reserved for the powerful and famous. Often costly and time-consuming to produce, the sitters usually insist on dignified, even idealized, likenesses that honor the particular character they want to project. Because portrait busts are often displayed in public, they celebrate the sitters while they are alive and memorialize them after they die. Savage, similar to American artists from the Ashcan school, challenged this tradition by sculpting a bust of a street-dwelling child, then an everyday sight in urban centers like New York, where she lived. In using a French word to title the work, she also revealed her affiliation with a French art trend that invested value in everyday scenes and subjects.

Yet the bust also challenges a different sort of convention. As a mother and as founder of the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts in Harlem, where she taught children from her neighborhood, Savage was deeply concerned with the welfare of African American children. Yet in the 1920s there were few public programs to help the poorest inner-city children. In many cases, homeless black children, often labeled as hoodlums, were barred from adoption agencies and instead interned in public institutions, like New York's notorious Colored Orphan Asylum. The situation began to change in the 1930s, in large part because black communities, like those in Harlem, worked to raise awareness about children's needs and the inferior assistance black children received. Savage's sculpture, dating from about 1929, can be seen in this context. Using a classical form while preserving lifelike, individualized details, Savage honored homeless children as individuals who deserve respect and affection. Indeed, the tenderness and detail of the portrait partly stem from her choice of model: her nephew, Ellis Ford. Widely collected and publicized, Savage's work helped increase black children's visibility.

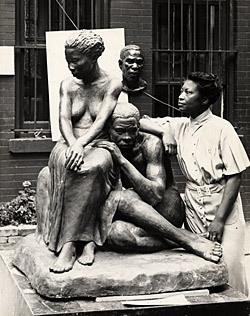

About This Artist

Augusta Savage (born Green Cove Spring, FL 1892–died New York City 1962)

Augusta Savage was a renowned sculptor and teacher who effectively used her work to challenge discrimination and promote civil and women’s rights. Dedicated to expanding educational and professional opportunities for African American artists, she founded the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts in Harlem, which was later developed into the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA’s) Harlem Community Art Center. Through her work at these institutions, she not only nurtured the careers of many younger African American artists, including Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight, and Norman Lewis, but she also actively challenged the biases among WPA administrators by insisting African American artists deserved support. As an artist, however, Savage often struggled to find backers for her own work. When she arrived in New York City in 1921, she met with some initial success, receiving commissions to produce busts of W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. Such works won her the attention of African American community groups. Their support combined with a Rosenwald Fellowship enabled her to study and exhibit in Paris. After returning to America, she sculpted a huge plaster for the 1939 World’s Fair inspired by “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a song considered a Negro anthem. Like much of her work, it was not cast in bronze and was later destroyed. She created fewer artworks after 1940, when she moved to upstate New York, though she continued to teach.