Charles White (1918–1979), Move On Up a Little Higher, 1961, charcoal and Wolff carbon pencil on board, 40 3/16 x 48 1/4 in., National Museum of African American History and Culture, Museum purchase, TR2009-9

Student Questions

1. Describe the woman’s pose and gesture. What do you think she is doing?

2. Look at her clothing. What does it remind you of?

3. How would you describe the mood or tone of this artwork? How does the artist convey that impression?

About This Artwork

Charles White creates an inspirational work with Move On Up a Little Higher, a drawing named after a bestselling gospel song recorded by the legendary Mahalia Jackson. Here he helps us experience the moving lyric "I'm gonna ... lay down my heavy burdens [and] put on my robe in glory." A seated black woman lifts her arms above her head, palms turned toward the sky in an act of praise. Her eyes are cast down and her brow is furrowed. Her cropped hair frames her somber, weathered face, and she wears a full gown that looks like a choir robe. Although the setting is indistinct, a bright, heavenly light surrounds her, perhaps even radiates from her. The vertical lines White drew around her reinforce a sense of uplifting movement.

When Jackson released "Move On Up a Little Higher" in 1948, it launched her to international fame. She soon began performing to sold-out venues and became the host of a popular radio and television show based in Chicago, all of which attracted widening audiences to the African America gospel tradition. Her music also brought attention to the civil rights struggle, especially after she met Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King at the 1956 National Baptist Convention and began performing her gospel songs at civil rights rallies and demonstrations, like the Montgomery bus boycott. Drawing on a musical tradition that dates to the era of slavery, gospel songs—with their uplifting tones and themes—helped unify and strengthen the resolve of civil rights activists. Their Christian values also fortified participants, many of whom shared a deep religious conviction and felt a spiritual devotion to achieving civil rights.

Living and teaching in California since 1956, White was removed from what seemed like the front lines of the civil rights struggle in the early 1960s and from the progressive artists he had known earlier in his career, when he worked in Chicago and New York. Yet White's perspective from California enabled him to think creatively about the Civil Rights movement. Far from the harsh realities of segregation and violence, he felt free to create symbolic images, artworks that promoted civil rights differently than literal portrayals of the struggle. As seen with Move On Up a Little Higher, White's drawings could produce an emotional experience akin to that of music, an effect one Los Angeles critic called "visual spirituals."

About This Artist

Charles White (born Chicago, IL 1918–died Los Angeles, CA, 1979)

Charles White’s artwork creates a moving record of African American life from the 1930s through the 1970s. He explained: "My main concern is to get my work before common, ordinary people …. Art should take its place as one of the necessitates [sic.] of life, like food, clothing and shelter." As a child, White was interested in art and after high school received a scholarship to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. In about 1938 he joined the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as an easel painter and went on to create a mural of five notable African Americans for the Chicago Public Library. Between 1942 and 1943 he received a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship to study at the Art Students League in New York City, which culminated in his painting a mural about African American history at Hampton Institute, in Hampton, Virginia. After serving in World War II in 1944 as a camouflage artist, he settled in New York City. In the late 1940s, White traveled to Mexico City to make prints at the famous workshop Taller de Gráfica Popular with his first wife, Elizabeth Catlett. Settling in Southern California in 1957, White taught at the Otis Art Institute from 1965 until his death in 1979.

Related Material

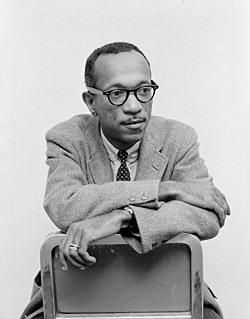

Carl Van Vechten, Mahalia Jackson (from the series Noble Black Women: The Harlem Renaissance and After), 1933, printed by Richard Benson. Palladium print, n.d., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts, 1983.63.134

Although it had long been central to African American culture, religion, especially in the form of gospel music, took on special importance during the Civil Rights movement. Charles White’s drawing Move on Up A Little Higher takes its name from a song performed by Mahalia Jackson, pictured here as if in prayer. Jackson’s moving performances and popular recordings created a worldwide audience for gospel music. Jackson toured widely in the 1930s and became an enthusiastic proponent of civil rights, performing numerous benefit concerts to support the movement.

P. P. Bliss and Ira D. Sankey, Gospel Hymns No. 2, 1876. National Museum of African American History & Culture, Gift of Charles L. Blockson

The importance of religion in the struggle for freedom and equality did not begin with the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. As this hymnal indicates, African American activists often turned to religion to provide moral guidance and spiritual sustenance. Owned by Harriet Tubman, who led slaves to freedom along the Underground Railroad, the hymnal indicates Tubman’s reliance on her faith. When the book is opened, the pages fall to hymns Tubman read frequently. This deeply personal artifact suggests the emotional demands of standing up for freedom and the strong resolve it required.

Laura Wheeler Waring, James Weldon Johnson, 1943, Oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 30 in. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the Harmon Foundation, NPG.67.40

Music played an essential role in the Civil Rights movement. James Weldon Johnson, shown in this portrait, penned lyrics for the spiritual "Lift Every Voice and Sing"—called the "Negro National Anthem"—in 1900. In 1919 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People adopted the song as its anthem, and the tune again became popular in the 1960s at the height of the Civil Rights movement.