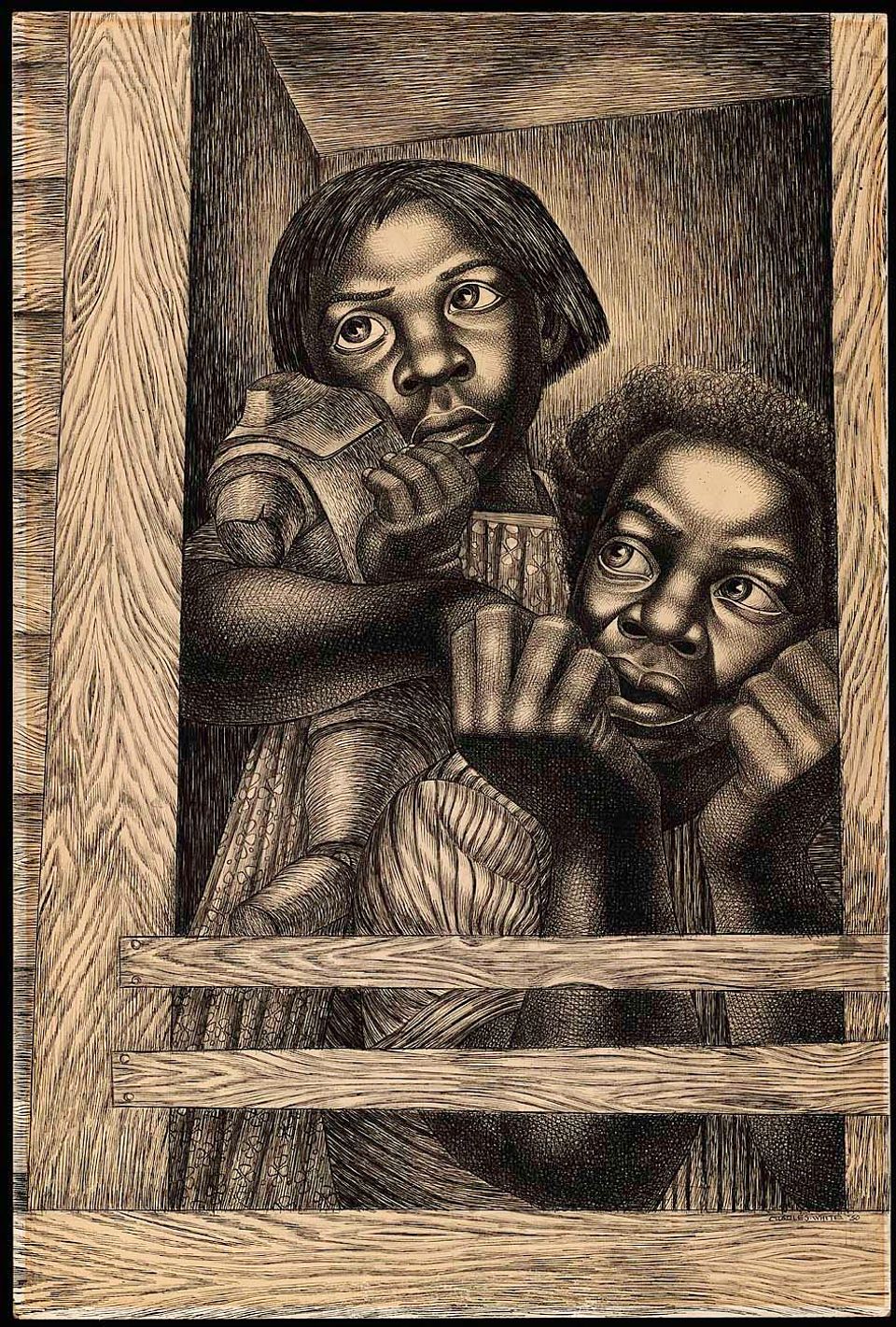

Charles White (1918–1979), The Children, 1950, ink and pencil on paper, 29 3/4 x 20 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Julie Seitzman and museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2009.13

Student Questions

1. Look at the two figures. How would you describe their expressions and moods?

2. Where are they? Why do you think the artist chose to present them in a cramped space?

3. Charles White used ink and pencil to create this scene. What patterns and textures do you see? How does he create highlights and shadows?

About This Artwork

Charles White's drawing exudes an anxious, uneasy mood. He carefully renders the figures so that viewers identify with their apprehensions. The girl in the background, for example, clutches a headless doll, as if hoping it will provide solace. The figure in front of her—which may be her mother or perhaps a brother—holds up large, powerful hands to her or his face, another disturbing sign. Although the pair inhabit the same space and glance in a similar direction, they seem detached from one another, as if their worries isolate them.

White's composition heightens his subjects' anxieties. He cramped the figures together in a small room, which is visible only through a narrow window. The vantage confines the pair, providing the sense that they are boxed-in or restricted, and the busy shadows behind them are sure signs that something is not quite right. The window's wooden frame and the slats that cross in front of them strike a tension between the boards' flat surface and the three-dimensional figures, made realistic with thousands of fine lines and crosshatching. Compressing the voluminous figures behind the window's flat surface, White makes their agitation palpable.

For White, the late 1940s and early 1950s were a deeply anxious time. As a left-wing artist who associated with progressives and members of the Communist Party, he felt the constant threat of political persecution, especially after the McCarran Act of 1950 criminalized activities perceived to be subversive. White himself was monitored by the FBI, and in 1950 White was summoned to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, the federal organization leading investigations of alleged subversives at the time. The committee eventually withdrew the summons before White was scheduled to appear.

While White's art may convey some of his personal anxieties, he deliberately related his work to social issues of particular importance to African Americans, seeing himself as a "spokesman for my people." Around 1950, when White created this drawing, school desegregation had become the prevailing civil rights issue for many African American families. It may also have been especially significant to White, who married and began his own family that year. Since the 1930s, thousands of African Americans had joined protests against school segregation. Yet in 1950, civil rights leaders used new tactics to show that segregation was not simply unfair but also psychologically damaging to black children. To provoke legal battles, these leaders encouraged black children in certain communities to try to attend all-white schools, knowing they would be turned away. Five key cases began to make headlines in 1950 and culminated in the 1954 landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled school segregation illegal.

White's drawing may not be a commentary on the school desegregation movement per se. Nevertheless, by portraying two African American figures within a confined space, White seems to register the psychological torment African American families endured during the era of segregation.

About This Artist

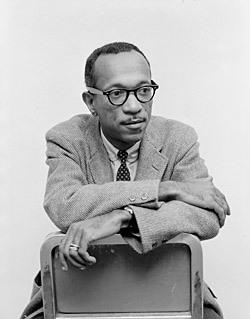

Charles White (born Chicago, IL 1918–died Los Angeles, CA, 1979)

Charles White’s artwork creates a moving record of African American life from the 1930s through the 1970s. He explained: "My main concern is to get my work before common, ordinary people …. Art should take its place as one of the necessitates [sic.] of life, like food, clothing and shelter." As a child, White was interested in art and after high school received a scholarship to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. In about 1938 he joined the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as an easel painter and went on to create a mural of five notable African Americans for the Chicago Public Library. Between 1942 and 1943 he received a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship to study at the Art Students League in New York City, which culminated in his painting a mural about African American history at Hampton Institute, in Hampton, Virginia. After serving in World War II in 1944 as a camouflage artist, he settled in New York City. In the late 1940s, White traveled to Mexico City to make prints at the famous workshop Taller de Gráfica Popular with his first wife, Elizabeth Catlett. Settling in Southern California in 1957, White taught at the Otis Art Institute from 1965 until his death in 1979.

Wayne F. Miller, Girl seated on doorstep with a newspaper in her lap, about 1946. © Wayne F. Miller, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture

Many midcentury artists explored the uncertainties of daily life. Wayne Miller’s photograph of a girl seated on a doorstep draws on a documentary tradition to set a mood of isolation and unease. Miller’s wider body of work focused on Chicago’s South Side in the period following World War II and offers an intimate portrait of a cohesive urban community despite poverty and despair.

Selma Burke, Untitled (Woman and Child), about 1950. Painted red oak, 47 1/8 x 12 3/4 x 11 3/4 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John A. Sakal and Terry L. Bengel in honor of Dr. Paul Albert Chew, Founding Director of the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, Pennsylvania, 2004.20

While some midcentury African American artists drew on racial themes, others sought to transcend such distinctions. Basing her sculptures on universal relationships, like the one seen here between mother and child, Selma Burke wanted her art to be seen without racial labels. In this work, the figures emerge from a roughhewn trunk-like base and their bodies seem to merge, suggesting their relationship is as natural as the wood from which it is carved.

Listen to Mweupe Mlfalme Nguni remembers his first day at an integrated elementary school in 1965.

Warning: This audio clip contains a word used to describe African Americans that is considered to be offensive by many. Historically, the word was used to describe African Americans in a derogatory manner. We have included it in this material because we feel that it is our duty to present oral histories and primary sources that tell the entire historical truth without censorship.

In this recording, the word is spoken by individuals whose lives were touched by racism. In our complex society, the word is still used today in popular culture, among cohorts, and by those who one might classify as racist.

Please listen to the recording prior to classroom use to determine if it is appropriate for your students. If you elect not to use this electronic resource, please note that non-audio materials do not contain any use of this word.

StoryCorps, National Museum of African American History and Culture