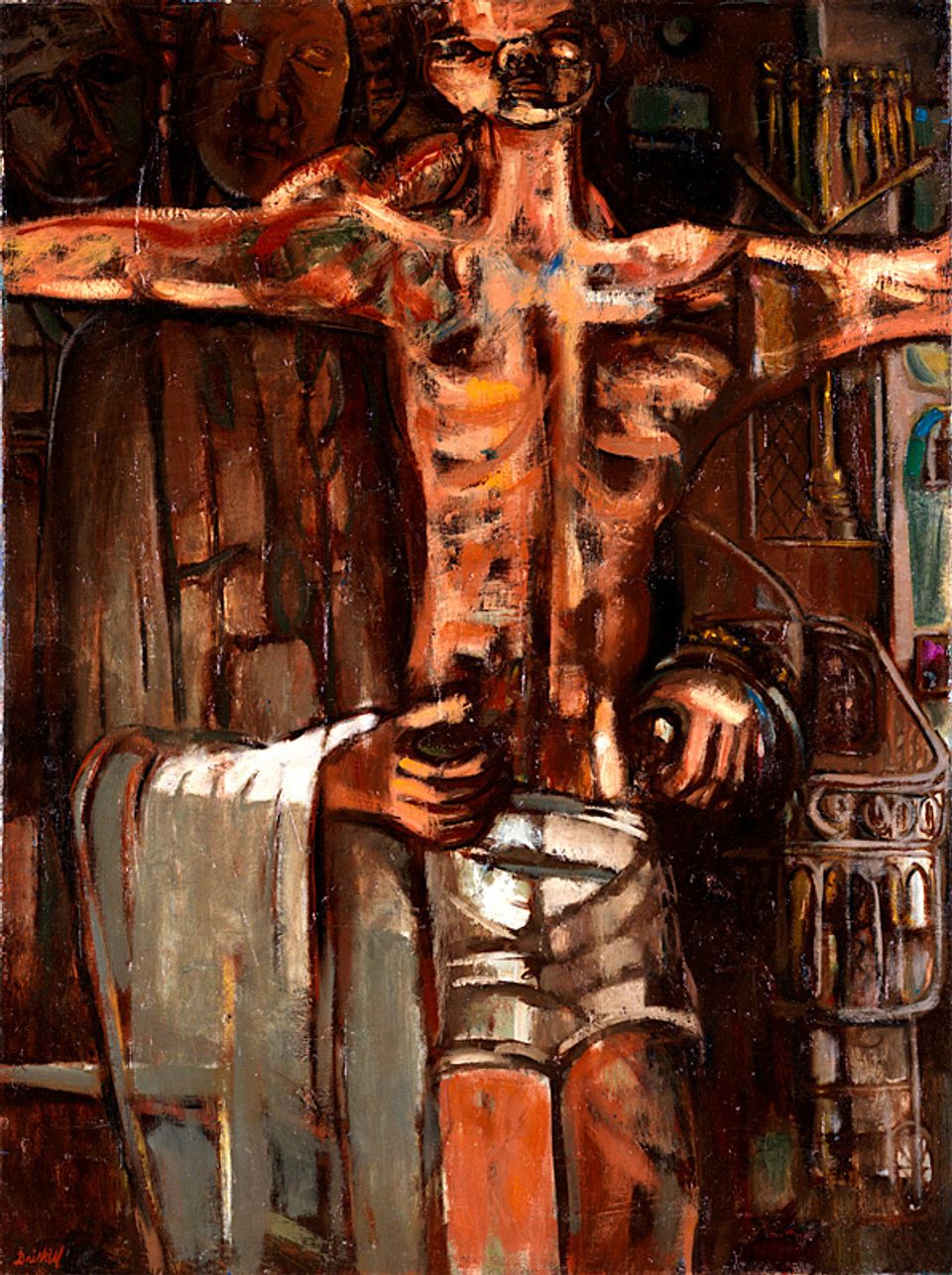

David C. Driskell (b. 1931), Behold Thy Son, 1956, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in., © David C. Driskell, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture, Museum Purchase, TR2009-7

Student Questions

1. Why do you think David Driskell painted the main figure so the head, hands, and feet do not fit in the frame?

2. Who do you think is holding the “son”?

3. Have you seen other images like this one? What clues make you think of these other images?

About This Artwork

While visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, in the summer of 1955, fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was kidnapped, beaten, and murdered for allegedly speaking to a white woman. After his body was retrieved from a river and returned to his family for burial, Till's mother, Mamie, insisted that her son's body be displayed in an open casket, where the thousands of mourners and reporters who attended his funeral would see it. She also distributed a photograph of his mutilated corpse to the press, asking them, "Have you ever ... had [a son] returned to you in a pine box, so horribly battered and water-logged that someone needs to tell you this sickening sight is your son—lynched?" Although the white media refused to publish the photograph in its coverage of the murder, the gruesome image was widely circulated by some African American periodicals, including Jet magazine. Till's mother later explained why she decided to put her son's body on public display: "They had to see what I had seen. The whole nation had to bear witness to this."

Just weeks after Till's body was discovered, artist David C. Driskell moved from Washington, D.C., to the South with his young family. Driskell found Till's lynching to be a poignant wake-up call to the appalling violence borne of Jim Crow segregation and racism. He later said, "This crime awakened in most African Americans a sense of rage that helped prepare us for the revolutionary journey [to fight for justice and equality that] we would eventually take." Driskell decided to paint Behold Thy Son because he "was well aware of the power of social commentary art and its use to stir the consciousness of a people." He gained this insight largely from his training at the Skowhegan artists' colony and at Howard University.

Using heavy, dark outlines and bright highlights so that his painting resembles a stained glass window, Driskell depicted a figure with his arms outstretched as if crucified. A woman holds out the body, embracing and supporting it—much like religious sculptures and paintings of the Pieta—but also offering it uncomfortably close to the viewer, so close that its limbs are severed by the edges of the canvas. Although Driskell provided details suggesting Till's battered body and face, the sacrificial theme and religious symbols transcend the event. The painting connects those who have suffered injustices in order to save others. Driskell explained that he intended to portray "the sacrifice of many young lives from Christ to Till."

About This Artist

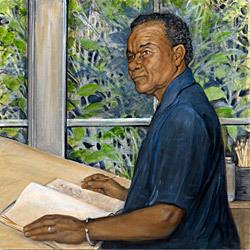

David C. Driskell (born Eatonton, GA 1931–died Washington, DC 2020)

A highly regarded painter, art collector, and authority on African American art, David C. Driskell has played an important role in bringing African American art to a wide audience. After studying art at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Howard University, and Catholic University, Driskell became a professor at the University of Maryland. Driskell has greatly advanced the study of African American art through his teaching career and by organizing numerous museum and gallery exhibitions, including the foundational 1976 exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750–1950. All the while, Driskell has produced his own artwork—colorful, abstract pieces, which draw on symbols from cultures throughout the world. Driskell has said, “I make art to free myself, to give a new dimension to life, and hopefully to other people’s lives…. Part of the message that I desire to communicate in my art is that I am a black American…. But my art is heavily imbued with Western forms.” In 2000, Driskell received the National Humanities Medal, and in 2007 he was elected to the National Academy, an honorary association of professional artists who have made outstanding contributions to their fields.

Related Material

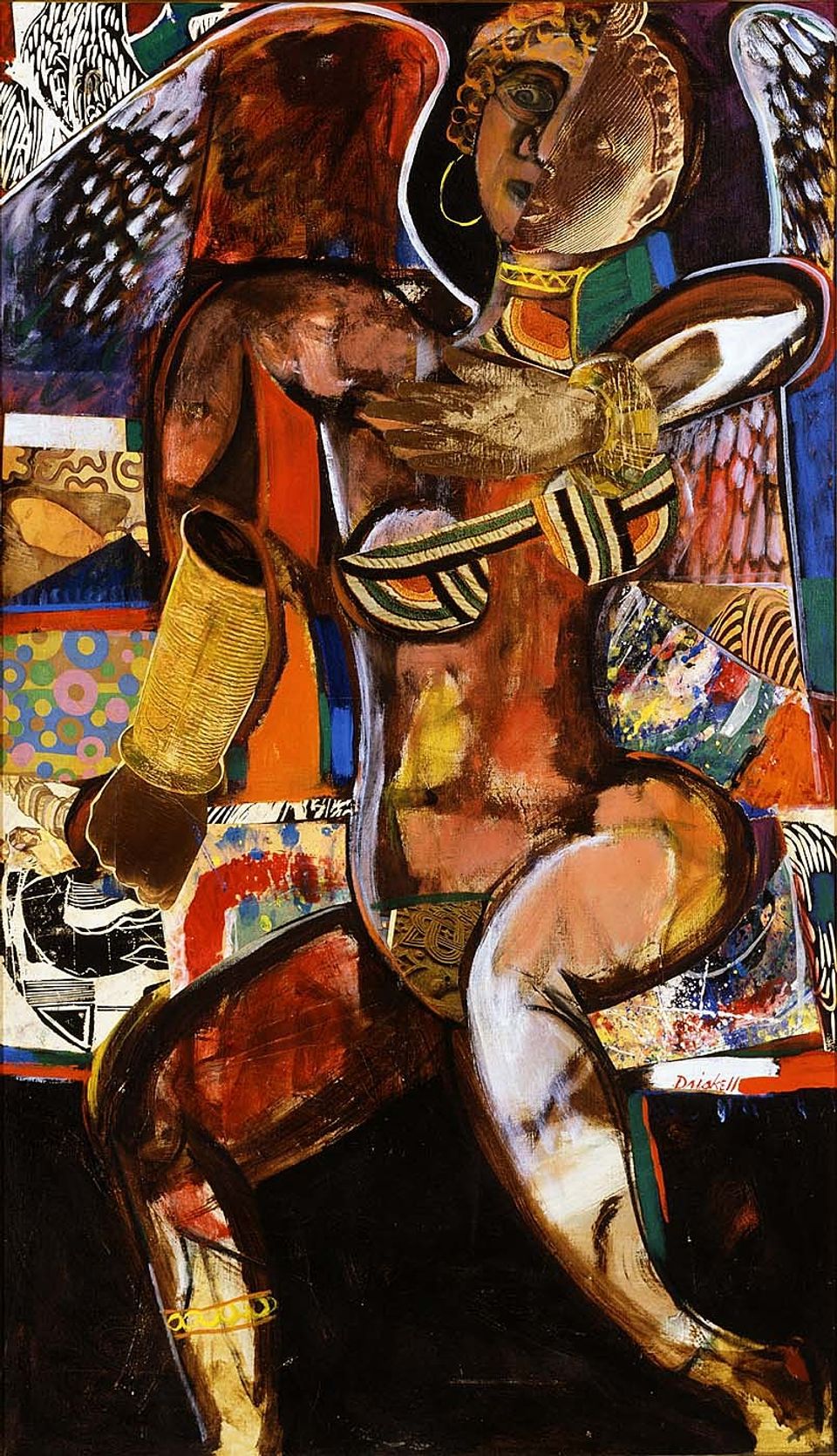

David Driskell, Dancing Angel, 1974. Oil, fabric, and collage on canvas, 60 x 40 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Cynthia Shoats and museum purchase, © 1974 David C. Driskell, 2004.27

As an artist, teacher, and scholar, David Driskell has been instrumental in revealing the deep connections between African American culture and the global diaspora—the migrations of African peoples around the world. Assimilating these varying places and influences, Driskell draws on Islamic, Greek, Indian, African, and modern art traditions in the painting Dancing Angel. The heavenly figure, a lively but reverent collage, expresses the deep cultural relationships that cut across place and time. In the decade before painting Dancing Angel, Driskell had studied these cultures and art forms as he traveled throughout Europe and Africa.

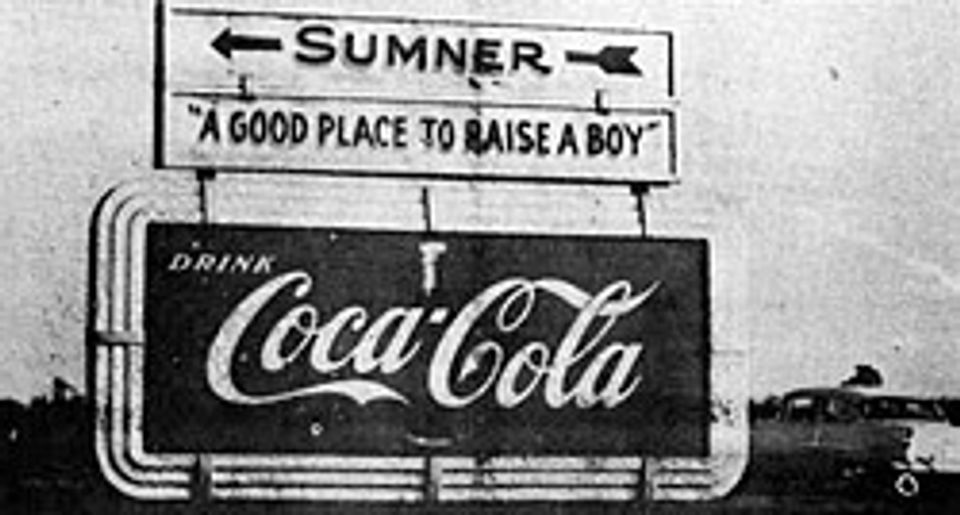

Ernest C. Withers, from The Complete Photo Story of Till Murder Case, 1956, Offset lithograph on paper, © Ernest C. Withers Trust, Memphis, TN, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture

Like Driskell’s Behold Thy Son, Ernest C. Withers’s photograph addresses the story of Emmett Till. Withers’s picture, however, conveys a deeply ironic message. The road sign directs motorists to Sumner, Mississippi, dubbed "A Good Place to Raise a Boy." In 1955, an all-white jury in the small town of Sumner acquitted two white men of the brutal murder of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old African American. Afterward, Withers compiled a book of photos, including this one, to raise awareness about the white community’s complicity in the lynching and cover-up.

Henry Clay Anderson, Evidence of Vandalism, 1955. National Museum of African American History and Culture

Henry Clay Anderson took this photograph of the car of civil rights leader George Lee after his murder, which occurred just months before the slaying of Emmet Till. Photographers of such scenes risked their safety to expose the severity of racial violence. As these images circulated, they helped convince the nation of racism’s threat to democracy.

Ten shards of stained glass and one shotgun shell, from the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, 1963. National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from the Trumpauer-Mulholland Collection

On Sunday, September 15, 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church—the largest African American church in Birmingham, Alabama—was bombed. The explosion killed four girls: Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Denise McNair. In riots following the bombing, two more teenagers were killed. Joan Trumpauer Mulholland, a Freedom Rider and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee worker, gathered these glass shards and shotgun shell from the gutter outside the church during a funeral for some of the victims.