Earlie Hudnall Jr. (b. 1946), The Guardian, 1990, gelatin silver print, 19 7/8 x 16 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase, © 1990 Earlie Hudnall, Jr., 1994.23.4

Student Questions

1. What is reflected in the man’s sunglasses? What other object is prominent in the picture?

2. How would you describe the interaction between the man and the girl?

3. Why do you think Hudnall excluded other people from the image?

Download This Artwork

About This Artwork

Earlie Hudnall's double portrait provides a positive image of black fatherhood. The photographer took the picture at the girl's eye level, and we are immediately drawn to her smiling face, framed by her white coat, hood, and scarf. Apparently her winter outfit is not warm enough because she is snuggled up against a man who towers above her and the viewer. Although the man looks off into the distance, his large sunglasses mirroring a cityscape, he nonetheless assumes his role as "guardian." He has tucked the girl inside his big, plush coat, and linked his hands together in front, embracing her securely. Together the two form a large triangle that fills the foreground. The straightforward, symmetrical composition suggests that the relationship is stable and solid. Behind the man's head is a small American flag, the kind waved by the hundreds during parades on the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving. Whether shooting at a parade or some other event—the setting is not specific—Hudnall uses the flag to emphasize wholesome values and patriotism.

When Hudnall took this picture, representations of black men were highly contested. Mass media images often depicted black men variously as criminal, promiscuous, violent, or irresponsible. Alarming statistics seemed to back this characterization. For example, in 1990, the year of Hudnall's photograph, about 2.3 million black men and boys were incarcerated while about twenty-three thousand graduated from college (a ratio of 99:1, compared with the 6:1 ratio for whites). Noting a crisis, many community, church, and political leaders called for black men to take a more active role in raising their children. Against prevailing representations of black men, activists offered a counter-representation: the image of the wholesome black father.

In both cases, black men were frequently assigned roles that relied on or reacted to stereotypes and statistics. Hudnall's photograph offers something different. By foregrounding the relationship between the beaming young girl and her father rather than focusing exclusively on the man as a representation of his race, the father becomes a multidimensional figure. In other words, he can be himself, defined by his relationships and his actions rather than the color of his skin.

1. Statistics cited in Henry Louis Gates Jr., "Preface," Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art (Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994), 13.

About This Artist

Earlie Hudnall Jr. (born Hattiesburg, MS 1946)

Inspired by his father, who was an amateur photographer, and his grandmother, who was the keeper of the family scrapbook, Earlie Hudnall Jr. began photographing in the 1960s while in the Marine Corps. He later studied art at Texas Southern University in Houston under department head John Biggers. Hudnall recalled that Biggers told his students that “art is life” and explained that artists must draw upon their experiences with family, community, and life in making their work. Hudnall took this advice seriously and created an extraordinary record of African American life, mainly in Texas, Mississippi, and Georgia. Hudnall wrote, “I chose to use the camera as a tool to document different aspects of life—who we are, what we are, how we live, and what our communities look like …. What is important is the ability to transform … a moment, into a meaningful, expressive, and profound statement.”

Related Material

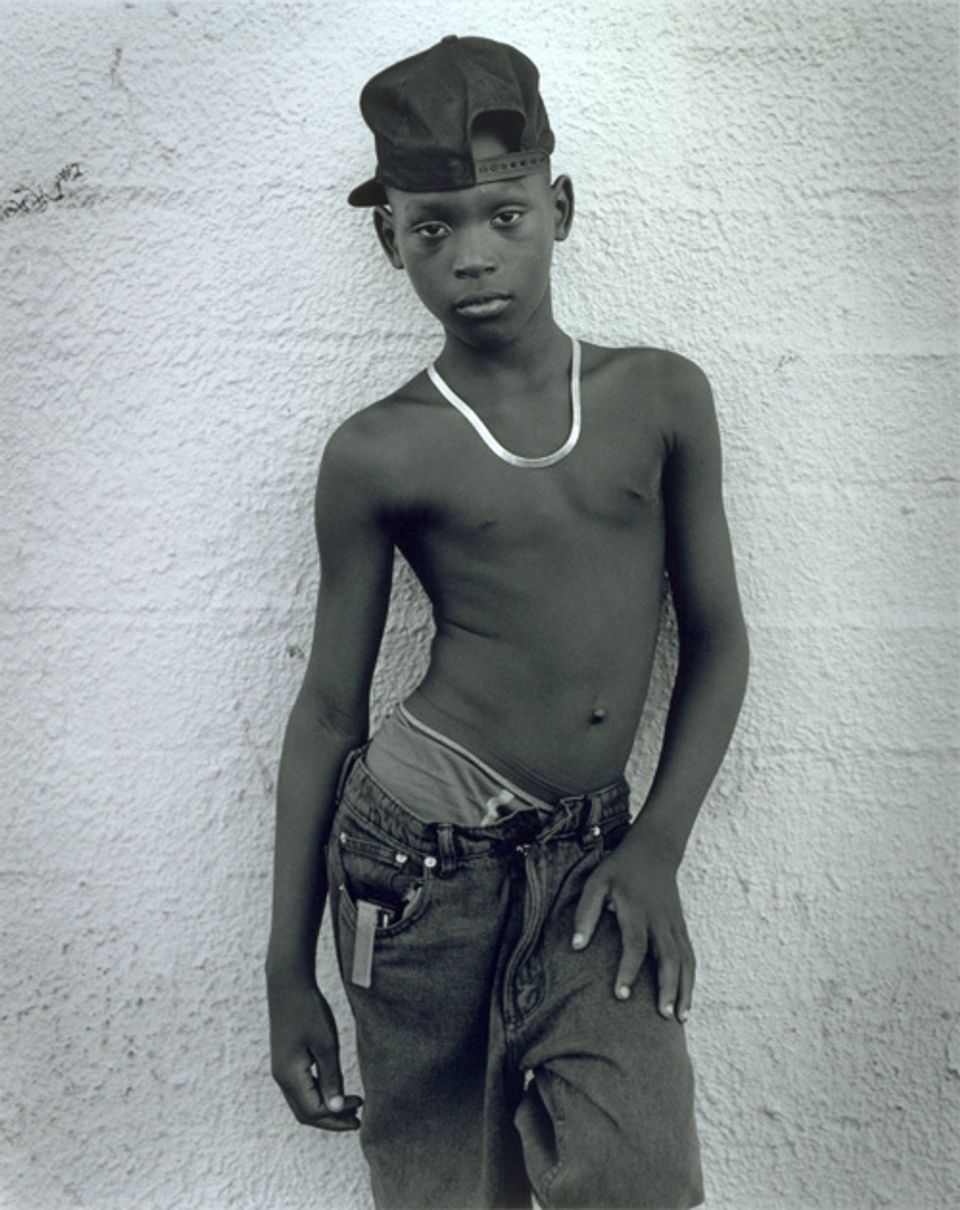

Earlie Hudnall Jr., Flipping Boy, 1983. Gelatin silver print, 19 7/8 x 16 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase, © 1983 Earlie Hudnall, Jr., 1994.23.2

Earlie Hudnall Jr., Hip Hop, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 19 7/8 x 16 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase, © 1993 Earlie Hudnall, Jr.,1994.23.7

Earlie Hudnall’s photographs often feature children to convey the hopes and challenges of life in African American communities in Texas. In Hip Hop (below), a child assumes the stance and expression of someone far older. His backward hat, gold chain, low-slung pants, and pager confirm that his experiences exceed his outward age. Flipping Boy suggests Hudnall’s reason for focusing on these contradictory figures. In that scene, the acrobat conveys an instance of beauty but also of strangeness, a frozen moment that reveals the topsy-turvy experiences that characterize his subjects’ daily lives.

Romare Bearden, Untitled (Black in America), about 1974. Lithograph, 12/50, 31 ½ x 21 ¼ in. Art © Romare Bearden Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture

Jim Wallace, photo from Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1964. © Jim Wallace, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of James H Wallace Jr

Like Hudnall, many artists have used the potent symbolism of the American flag to convey complex, often ironic messages. In both Romare Bearden’s lithograph (top) and Jim Wallace’s documentary photograph, black figures are wrapped in American flags that both frame and obscure them. These compositions reveal the tensions inherent in patriotism and activism.

Million Man March pin, 1995. National Museum of African American History and Culture

Produced for the Million Man March in Washington, D.C., in 1995, this button was designed to visually and conceptually link to the protest tradition of the Civil Rights movement. Marchers converged on the National Mall, just as they did in the 1963 March on Washington. But this time participants demanded that politicians address issues that disproportionately affected black men, including poverty and unemployment. Although widely supported by many African American leaders, the event was not without controversy. The march’s leader, Louis Farrakhan, was seen by some as a divisive figure. In addition, many thought the march excluded women and contradicted its goal of advocating for black families.