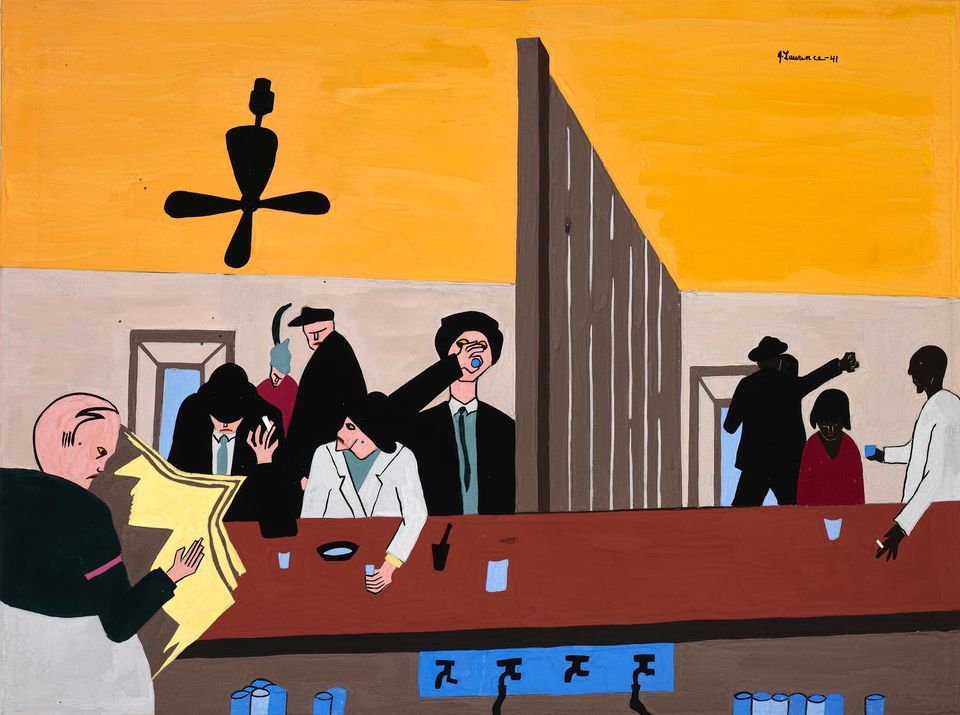

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Dixie Café, 1948, ink on paper, 17 x 22 1/4 in., National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Margaret and Michael Asch, TR2010-19

Student Questions

1. In Dixie Café, the artist depicts two groups of people. What do they have in common? How are they different?

2. What do the words in the artwork mean? Can you guess the time period shown?

3. What shapes and colors stand out? Why did the artist use these stark contrasts?

About This Artwork

In Dixie Café, Jacob Lawrence confronts a shameful fact of life in mid-twentieth-century America: racial segregation in restaurants and other public places. With stark, often jagged black-and-white shapes, Lawrence sets viewers on the sidewalk right outside the entrance to the Dixie Belle café. The compressed space, vertical lines, and stark black-and-white palette heighten the compositional tension.

Similar in style and theme to a series of illustrations Lawrence created for One Way Ticket, a 1949 volume of poetry by Langston Hughes, the artist may have based this picture on an actual café he saw when he visited the South in 1947. Without a doubt, the Dixie Belle stands for the hundreds of segregated restaurants found throughout the American South at midcentury. While signs below each window label the occupants “Colored” and “White,” it is impossible, without those labels, to confidently identify the race of the people in each side of the restaurant. In Lawrence’s depiction, everyone touched by Jim Crow is similar.

The hunched figures, each of them seemingly isolated, imply that segregation is dehumanizing for all. The indiscernible faces suggest that appearances are superficial and deceptive and that all people are basically the same: all get hungry; all search for sustenance; and all must eat. Yet this scene is drained of life and color, and bounty is absent. By law throughout the South, and by custom in the North and West, racial minorities and whites were not allowed to eat, shop, swim, or travel together, nor could they share public bathroom facilities or drinking fountains until the mid-1960s.

Lawrence, a northerner raised in New Jersey and New York, often used his art to explore race, equality, and justice. This artistic approach is called social realism. Here he exposes Jim Crow, the demeaning system of laws and practices that prevented black Americans from participating with whites in various activities. This system began to appear during post–Civil War Reconstruction and persisted for more than a century before new legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, was enacted. While the Supreme Court declared state-sponsored school segregation unconstitutional in the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education, segregation in other areas of life continued until these major laws of the 1960s were passed.

About This Artist

Jacob Lawrence (born Atlantic City, NJ 1917–died Seattle, WA 2000)

Known for painting people and events in African American history, Jacob Lawrence developed his expressionist style of flattened forms and bold colors after studying and working with other black artists in Harlem, especially Charles Alston and Augusta Savage. Lawrence was in his early twenties when his sixty-panel series, The Migration of the Negro, which told the story of the Great Migration, was exhibited to wide acclaim in a prestigious New York gallery in 1941. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Lawrence also completed several series that celebrate historical figures such as John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and Harriet Tubman. For Lawrence, historical subjects were relevant to the contemporary moment. He wrote in a statement for the exhibition of his L’Ouverture series: “I didn’t do it as a historical thing but because I believe these things tie up the Negro today. We don’t have a physical slavery, but an economic slavery. If these people, who were so much worse off than the people today, could conquer their slavery, we can certainly do the same thing.” Over his long and influential career, Lawrence explored a wide range of subjects, though he often returned to those of special importance to African Americans.

Related Material

Jacob Lawrence, Bar & Grill, 1941. Gouache on paper, 16 3/4 x 22 3/4 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Henry Ward Ranger through the National Academy of Design, 2010.52

In Bar & Grill, Jacob Lawrence again draws upon his first visit to the South and depicts a segregated restaurant. Viewed from behind the bar, the room beyond is split into two sections by a wall. No one seems happy in either section, but certainly the area reserved for white patrons is more comfortable: a fan keeps them cool, and the bartender reads a paper nearby awaiting their next order.

Greensboro lunch counter, exhibition view. National Museum of American History, Behring Center

Four African American students sat at this "whites only" lunch counter at a Woolworth’s store in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960. When they ordered coffee, they were refused service but would not leave the store. The strategic sit-in sparked a boycott of the store that lasted six months and created a firestorm of national publicity. The desegregation of this lunch counter on July 25, 1960, and the chain-wide integration that began the next day, marked a major victory for the Civil Rights movement and a decisive step in overturning Jim Crow.

Joe Schwartz, White Only, Southern Maryland, 1930s. © Joe Schwartz, Collection of National Museum of African American History & Culture, Gift of Joe Schwartz

Segregation was enforced not only at large store chains in the South but also at small businesses, as shown in this photograph of a rural sandwich shop in Maryland. The sign directly above the door bars entrance to African Americans. Its appearance amidst the advertising signage attests to the everyday, even mundane, qualities of segregation in much of America at midcentury.

Listen to Jerome Smith talk about segregated streetcars.

StoryCorps, National Museum of African American History and Culture