Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), John Brown held Harpers Ferry for 12 hours. (No. 20 from the series The Legend of John Brown), 1977 (original painting dated 1944), screen print, 20 x 25 in., National Museum of African American History and Culture, Museum purchase, TR2007-8.1.20, Series TR2007-8.1.1 - TR2007-8.1.22

Student Questions

1. What objects and shapes are repeated in this print? How else does the artist emphasize their importance? What do they tell us about the action taking place?

2. What does the stance of the figures indicate? Can you guess the time of day shown?

3. Abolitionist John Brown stands at the far left of the image. How does the artist distinguish him from the other figures?

About This Artwork

Number twenty of twenty-two artworks in a series, this print shows a dramatic episode in the story of John Brown (1800–1859). Brown was a deeply religious white man who dedicated his life to anti-slavery causes. Well before the 1859 incident illustrated here, he had given up hope that slavery could be ended without violence. Intending to foment an uprising that would end slavery, Brown planned to raid the U.S. military arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and arm hundreds of slaves. He expected many slaves and other supporters to join the raid, but only twenty-one men showed up. Although the mixed-race group succeeded in taking over buildings where the guns were stored—the part of the story shown in this print— federal troops eventually overpowered Brown and his men. Tried for treason, murder, and inciting slaves to revolt, Brown was quickly convicted and hanged. The raid and trial became the most sensational news story of its day. Compelling a wide national audience to either sympathize with or condemn Brown, the story did much to provoke the Civil War.

Jacob Lawrence uses angular, solid-colored shapes to represent the tense standoff between Brown's rebels and federal forces. The raiders, heavily armed black and white men, brace themselves along a high wall. Heavy belts holding bullets hang around their waists. More bullet-laden belts are slung over their shoulders and lie on the ground. The men point their guns with attached swords, called bayonets, over the wall. They are ready to fire. To the far left is Brown with long, gray-streaked hair. Slung by a cord around his neck is a sword in the shape of a cross, which alludes to Brown's religious fervor. The cord also suggests the noose by which he would be hanged. As night gives way to day, the other men glance nervously at Brown and one another, the ominous conclusion to their battle becoming clear.

The memory of John Brown remained controversial into the twentieth century, yet for many African Americans, Brown was a hero. In the 1930s, Lawrence became increasingly interested in producing images of historical figures like Brown because they were rarely included in standard history texts. As Lawrence recalled in 1940, "[T]hey never taught Negro history in the public schools.... It was never studied seriously like regular subjects." Lawrence's series joined the efforts of many intellectuals, artists, and political leaders who aimed to reframe American history. Focusing on black people's agency—how their actions have shaped history—these activists broke from racist perceptions of black people as passive. The new histories not only insisted black people have been a major historical force but also offered an inspiring message about blacks' ability to affect the present.

When Lawrence painted The Legend of John Brown series in 1941, he drew on the tales he heard in his community, which portrayed Brown as a prophet who gave his life to end slavery. As the artist recollected, these oral stories described Brown and other champions of black history as "strong, daring, and heroic; and therefore we could and did relate to these heroes by means of poetry, song, and paint." In the late 1960s and 1970s, African American history was again highlighted in the hopes of countering racism and promoting black interests among a new generation. Because Lawrence's original paintings in the John Brown series were then too fragile to be displayed, Lawrence was commissioned to re-create the series as a portfolio of silkscreen prints in 1977.

About This Artist

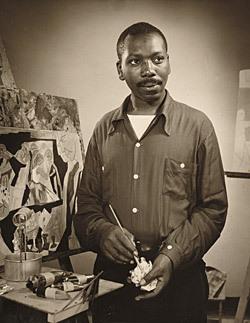

Jacob Lawrence (born Atlantic City, NJ 1917–died Seattle, WA 2000)

Known for painting people and events in African American history, Jacob Lawrence developed his expressionist style of flattened forms and bold colors after studying and working with other black artists in Harlem, especially Charles Alston and Augusta Savage. Lawrence was in his early twenties when his sixty-panel series, The Migration of the Negro, which told the story of the Great Migration, was exhibited to wide acclaim in a prestigious New York gallery in 1941. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Lawrence also completed several series that celebrate historical figures such as John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and Harriet Tubman. For Lawrence, historical subjects were relevant to the contemporary moment. He wrote in a statement for the exhibition of his L’Ouverture series: “I didn’t do it as a historical thing but because I believe these things tie up the Negro today. We don’t have a physical slavery, but an economic slavery. If these people, who were so much worse off than the people today, could conquer their slavery, we can certainly do the same thing.” Over his long and influential career, Lawrence explored a wide range of subjects, though he often returned to those of special importance to African Americans.

Related Material

Augustus Washington (photographer), John Brown, about 1846–1847. Quarter-plate daguerreotype, 4 1/2 x 7 3/4 x 7/16 in. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Purchased with major acquisition funds and with funds donated by Betty Adler Schermer in honor of her great-grandfather, August M. Bondi, NPG.96.123

The earliest known portrait of insurgent abolitionist John Brown was taken by the son of a former slave, Augustus Washington. Like Brown, Washington was deeply committed to the abolition of slavery, but he believed emancipation would not ultimately secure racial equality. In 1852, seeking a new life for himself and his family, he sailed to Liberia in West Africa, a nation founded by the American Colonization Society.

Sy Kattelson (photographer), Asa Philip Randolph, 1948. Gelatin silver print, 10 13/16 x 10 5/8 in. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, © Sy Kattelson, NPG.87.46

As in Jacob Lawrence’s John Brown series, others artists and activists have drawn parallels between slavery and contemporary conditions. In this picture, the labor leader A. Philip Randolph carries a sign that reads, "If we must die let us die as free men not Jim Crow slaves." As the first president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Randolph shaped the civil rights landscape in America for nearly a half-century. Perhaps most notably, he founded the March on Washington movement to protest blacks’ exclusion from defense jobs during World War II.

Sculock Studio (photographer), Dr. Carter G. Woodson, late 1940s. Photoprint. Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Dr. Carter G. Woodson, pictured here in his library, worked tirelessly to promote understanding of the importance of African American culture to American history. Woodson’s scholarship and teaching filled the gap left by historians who either misrepresented or ignored the contributions of black Americans to the nation’s history. He helped raise the historical awareness of many young African Americans, including artists like Jacob Lawrence.