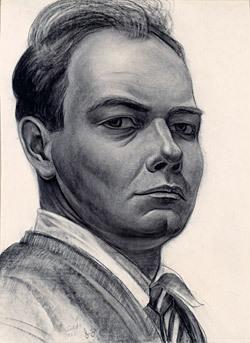

John Steuart Curry (1897–1946), The Fugitive, 1935, lithograph, 13 x 9 1/2 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Adelyn D. Breeskin, 1972.41

Student Questions

1. Who do you think is the “fugitive” in this artwork? Describe the person’s pose and facial expression.

2. What are the figures in the lower right area of the picture doing?

3. Why do you think Curry uses so much space for the leaves, tree, and moths?

About This Artwork

When this haunting image first appeared, few Americans could have seen it without associating it with mob violence against African Americans. A desperate man in torn overalls perches in a tree to hide, his back pressed against the trunk and his body bowed to follow its curve. Although he remains frozen, the busy leaves around him look like flickering flames, suggesting the fears that grip at him. Moths dance in shafts of moonlight that illuminate the woods and make it easier for a posse in a nearby clearing to follow a straining hound. The fugitive gazes skyward as if a miracle were his last hope. His pose strongly suggests the cucifixion of Jesus, and the trunk that conceals him resembles a pyre, confirming the suspicion that any encounter between this man and his pursuers will end in death.

In its condemnation of lynching, John Steuart Curry's lithograph joined many other images that had appeared in news reports, literature, and movies. Unlike those more common representations of lynching, which often made a lurid spectacle of the violence, Curry's print uses compositional tension to focus in on the fugitive's inner condition. While he uses crisp outlines to set off the fugitive's rigid pose from the otherwise frenzied setting, he also embeds the man into the scene by elongating his body against the tree's contours and by reducing contrast of the print. This handling foregrounds the fugitive, making him the unmistakable subject of the print, yet it also hems him in, subjecting him to the frightening, and potentially lethal, pursuit. In this compositional tension, Curry poignantly conveys the the fugitive's emotional stress: his fear of death and his hope of escape.

Curry, a white artist, contributed three works—two oil paintings and this print—to an antilynching exhibition presented by the NAACP in 1935 titled An Art Commentary on Lynching. An eclectic group of thirty-nine artists from a variety of racial and ethinic backgrounds participated in the show, which was organized to raise awareness about the prevalence and horror of mob violence. By the mid-1930s, decades of active crusades to ban this terrorist activity had failed. Although the exhibition, and others like it, attempted to galvanize support for newly introduced antilynching legislation, a federal law against lynching never passed.

About This Artist

John Steuart Curry (born Dunavant, KS 1897–died Madison, WI 1946)

John Steuart Curry was hailed as one of the great artists of American regionalism, a movement that focused on rural themes and the American heartland. Raised in Kansas, Curry studied art in Kansas City, Chicago, New York, and Paris, and he worked as an illustrator before receiving recognition as a painter. Curry wrote that he used his work “for the cause of social and political justice”—an artistic aim called social realism. In the 1930s, he created several works with anti-lynching themes and in 1935 participated in an NAACP anti-lynching exhibition. He completed Justice Defeating Mob Violence for the Department of Justice Building in Washington, D.C., one of two murals he painted as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) artist. For the Topeka State House in Kansas, Curry completed one of his most powerful and controversial images: a Moses-like representation of abolitionist John Brown in a mural titled Tragic Prelude.

Scurlock Studio (photographer), Scottsboro Mothers, about 1931 or 1933 negative. Photoprint. Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

In 1931, events surrounding the Scottsboro Boys took on the disturbing qualities of racist pursuit and injustice, similar to a lynching. On March 25, nine black teenagers traveling on a freight train were arrested in Alabama. Although police had been called to investigate a fight, after talking with two white women on the train, officers charged the teens with rape. By April 9, eight of the teens, known as the Scottsboro Boys, were found guilty and sentenced to death by all-white juries. Appeals, however, continued for years. The cases are now seen as examples of the racism of all-white juries in the South. Some of the defendants’ mothers, included in this picture, helped rally demonstrations and protests worldwide during the defendants’ appeals.

David Smith, Private Law and Order Leagues (study for medallion, Medals for Dishonor series), about 1938–1939. Felt-tipped pen and ink and pen and ink on paper, 10 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase made possible by Olin Dows, 1988.60

David Smith, Private Law and Order Leagues (study for medallion, Medals for Dishonor series), about 1938–1939. Felt-tipped pen and ink and pen and ink on paper, 10 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase made possible by Olin Dows, 1988.60

Like Curry’s print The Fugitive, David Smith's Private Law and Order Leagues conjures disturbing images of injustice and racism. Smith made this preparatory drawing for his Medals for Dishonor series—a word-play on the highly regarded U.S. military decoration, the Medal of Honor. Smith intended the medals, eventually struck in bronze, to be a sarcastic commemoration of changes in the United States—including escalations of violence and avarice and the rise of fascism. In this nightmarish scene, crosses become swastikas, pulpits become gallows, and mountains become Ku Klux Klan hoods.

Herbert Singleton, The Way We Was, 1990. Carved and painted wood, metal locks, and hinges, 97 x 38 1/2 x 2 1/2 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Chuck and Jan Rosenak and museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, © 1990 Herbert Singleton, 1997.124.88

Contemporary artists continue to evoke the memory of racial violence and haunting aspects of the nation’s past. In this relief carving on an old door, Herbert Singleton draws on potent imagery of slaves carrying cotton, a black nanny suckling a white baby, a slave master brandishing a whip, and a Klansman overseeing a lynching to send a complex message about both historic violence and civil rights advances.