Norman Lewis (1909–1979), Evening Rendezvous, 1962, oil on linen, 50 1/4 x 64 1/4 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase, 1994.32

Student Questions

1. “Rendezvous” is French for a meeting. The painting’s title, then, indicates the subject is an evening meeting. Do you think it takes place outside or inside? What clues you in?

2. Can you find figures in the artwork? Is it a small or large gathering?

3. What sort of meeting do you think is taking place? What elements give you that idea?

About This Artwork

At first glance, there is nothing recognizable in the subtle brushstrokes Norman Lewis painted on a field of soft, muted grays and greens. Yet the title Evening Rendezvous suggests there is more to this abstract work. For example, Lewis's use of vivid red, white, and blue is striking, in part because these colors are so closely associated with the U.S. flag. Looking closer, the white shapes appear spiky and distinct, evoking tiny figures dressed in white from head to toe who form a circle on the left side of the painting and in clusters elsewhere. Meanwhile, the wispy reds and blues overlap and run together, seeming to flicker like flames. These details beg the question: What kind of evening rendezvous is this?

Nighttime gatherings of white-clad people flying the American flag call to mind the Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist organization that has used the guise of patriotism to rationalize attacks on African Americans and other minorities. During the Klan's meetings, which have often culminated in raids or terrifying public demonstrations, its members wear distinctive white robes and peaked hoods that mask their faces. The white figures in Lewis's painting resemble these costumes while the brilliant red areas evoke the bonfires, flaming crosses, and deadly bombings the Klan has used to menace supporters of civil rights and to destroy their homes and churches. The blue paint suggests smoke, billowing above the raging fires, and the mottled background evokes darkness partially lit by firelight. The field of red, white, and blue takes on an ironic meaning in this chilling context.

When Lewis abandoned realistic art in the 1940s and started creating abstract paintings—including semi-abstract works like Evening Rendezvous—many of his artist friends wondered why. As an African American painter, he was expected to address black issues. Because abstraction often has no easily identifiable subject, Lewis's friends thought it lacked political content. They discouraged him from abstract painting. Yet Lewis no longer believed that realistic depictions of troubled conditions could help solve society's problems. Instead, he was convinced that art should express an artist's personal feelings and vision. With Evening Rendezvous, Lewis demonstrated that his feelings were nonetheless politically resonant. As someone deeply committed to the struggle for equality and rights, he conveys the fear and sorrow caused by the Klan, merging art and politics through his own expressive style.

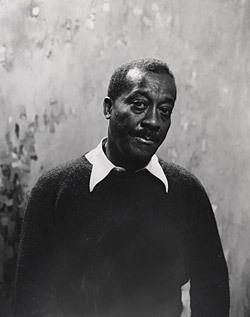

About This Artist

Norman Lewis (born New York City 1909–died New York City 1979)

Painter Norman Lewis was raised in Harlem and spent most of his life in New York City. Although mainly self-taught, he studied for a time with sculptor Augusta Savage, who encouraged the art careers of many young African Americans, and he also participated in the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA’s) art program. Early in his career, Lewis adopted a social realist style and depicted problems faced by working-class Americans. During World War II, however, Lewis began to wonder if his style and subject matter truly expressed his own identity and whether they served the interests of black Americans. As Lewis recalled in a 1977 interview, he came to believe that “painting pictures about social conditions doesn’t change the social conditions.” Instead, Lewis began experimenting with abstraction and soon produced completely abstract works, emerging as the first major African American member of the art movement known as abstract expressionism. Such works had no identifiable subject and artists created them primarily as a means of personal expression. Lewis was, nonetheless, deeply concerned with the problems of his times, and the African American struggle for civil rights preoccupied him and occasionally inspired his work. In 1963, he helped found Spiral, an African American artist group. He remained politically active for much of his career and a strong supporter of civil rights for all Americans, but he also wanted to convey broader ideas in his art. As he explained in a 1966 interview, “Political and social aspects should not be the primary concern; esthetic ideas should have preference.”

Related Material

Romare Bearden, Empress of the Blues, 1974. Acrylic and pencil on paper and printed paper on paperboard, 36 x 48 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase in part through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 1996.71

In the early 1960s, Norman Lewis joined a group of African American artists to discuss the place of black artists in the heady political climate of the civil rights era. Calling their group Spiral—because it suggests outward and upward movement—the members addressed a range of artistic issues they faced, particularly black identity in their work and discrimination in the art world. Because most of the members had adopted abstract styles with no obvious political content, the question of how to merge art and activism had special importance. The painting by Romare Bearden shown here suggests the ways this artist and others worked to integrate racial elements into work with broader themes.

Ku Klux Klan robe, about 1920s. National Museum of American History, Behring Center

Through intimidation, violence, and murder, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) sought to reverse the gains of the Civil Rights movement and restore white supremacy in both the North and South. Founded in the wake of the Civil War, the Klan was revived in the early twentieth century and thrived on terror. Over time, the KKK robe and hood became a feared symbol of the hatred and brutality that members directed at African Americans as well as immigrants, Catholics, and Jews.

Jim Wallace (photographer), Image from Interstate 88, NC, 1964. © Jim Wallace, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of James H Wallace Jr

The KKK hoped to end African Americans’ crusade for civil rights by intimidating black and white activists. The Klan held rallies and burned crosses, like this one photographed by Jim Wallace, a University of North Carolina student, in the summer of 1964 between Chapel Hill and Hillsboro. Wallace, who is white, photographed the rally to document what he thought was a great evil.

Kevin E. Cole, Increase Risk with Emotional Faith (part of the Fragment of Frozen Sound Series), 2008. Mixed media on wood. © 2008 Kevin Cole Photo by T.W. Meyer, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Greg and Yolanda Head, Photo by T. W. Meyer

In Increase Risk with Emotional Faith, Kevin E. Cole redirects the legacy of racial violence into something inspiring. The bright, wall-mounted sculpture employs a necktie motif that can be found in much of Cole’s work. The tie refers to a story Cole’s grandfather told him as a child. Pointing out a tree in their neighborhood, his grandfather recalled that white supremacists had used the tree to hang a group of black men by their neckties when they were attempting to vote. Meant to symbolize respectability, their ties had been used to humiliate and murder them. With this piece, Cole transforms his negative association by creating a dynamic celebration of strength and change.