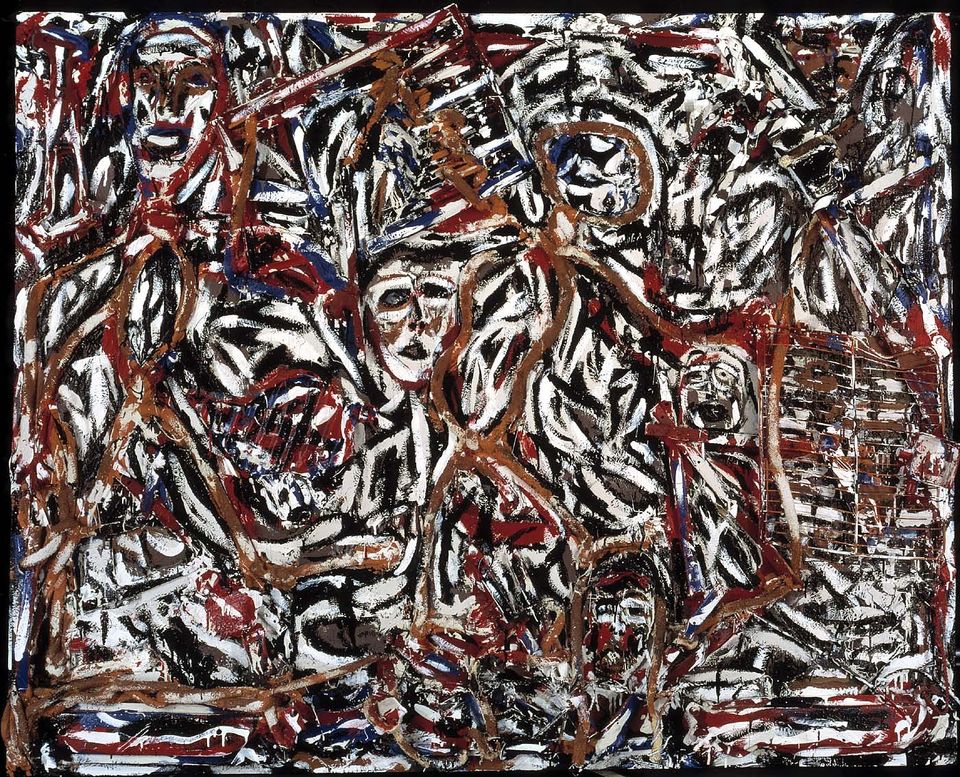

Thornton Dial Sr. (1928-2016), Top of the Line (Steel), 1992, mixed media: enamel, unbraided canvas roping, and metal on plywood, 65 x 81 x 7 7/8 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift from the collection of Ron and June Shelp, 1993.47

Student Questions

1. How many faces can you find in this artwork?

2. Look carefully at an enlargement of the artwork. In addition to paint, what else can you find? What do those pieces add to the assemblage?

3. Why do you think Thornton Dial attached these other items?

Download This Artwork

About This Artwork

In Thornton Dial's assemblage, masklike faces with staring eyes and open mouths emerge from a dense maze of layers streaked in red, white, blue, and black. Ropes painted brown snake over the surface, twisting into bodies that stretch from one side of the painting to the other. Additional objects have been attached to the surface—a paint-covered metal grill at the top and a wire rack on the right edge, for example—which accentuate the artwork's sculptural appearance. The resulting lattice of colors, forms, and objects gives the impression that, if the artwork's strata were excavated, much more could be discovered.

In many respects, "excavation" is an appropriate way to approach Top of the Line (Steel).By layering paint and objects that Dial collects from around his home in Bessemer, Alabama, a suburb of Birmingham, the artist creates a series of evocative relationships. Dial encourages viewers to look closely at the artwork, excavating meaning from the interplay of forms and even from the title, which has several interpretations. For example, "top of the line" refers both to a position in an assembly line and to high quality consumer goods. By including the word "steel," Dial refines his double meaning. Because Dial worked for many years in a factory shaping metal, steel refers to his own experience on "the line." At the same time, "steel" suggests its homonym "steal." The pun seems deliberate because Dial said he made this artwork in response to the 1992 looting that swept Los Angeles after Rodney King, an African American, was beaten by several white police officers.

With these dual references in mind, viewers can guess the multiple meanings behind Dial's work. For example, the figures made of brown rope that appear to hold metal objects can be seen in two ways. On the one hand, they resemble workers passing pieces of steel—as seen in the grill-like forms attached to the artwork's surface—along an assembly line. Alternatively, the figures look like they could be running off with the objects, literally stealing top-of-the-line appliances as horrified faces look on. By encoding these complex meanings in his intertwined layers, Dial makes a disturbing political critique: all these things—industrial labor, consumerism, rioting, and race relations—are, in fact, deeply connected. Speaking generally about his art, Dial said: "I make art that ain't speaking against nobody or for nobody either. Sometimes it be about what is wrong in life."

About This Artist

Thornton Dial Sr. (born Emelle, AL 1928-died McCalla, AL 2016)

Thornton Dial is a self-taught artist who uses discarded items that he finds around his small Alabama hometown to make striking artworks. Like many artists in the South who create art with humble materials, Dial has had no formal art training. Most folk artists like Dial are little known outside their communities, but collectors and museums have explored and celebrated the work of a few, including Dial. His work has been exhibited in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in the 1998 Whitney Biennial, and in other solo and group exhibitions. Among the materials Dial uses to create his art are rope, sticks, broken garden ornaments, mattress coils, old shoes, chicken wire, and discarded appliances, which he sometimes coats with house paint and enamel spray paint. His assemblages hang on the wall like paintings or stand on the ground like sculpture. Dial uses his work to address social and political problems, such as violence and war by using objects associated with those issues. Dial says: “It ain’t about paint. It ain’t about canvas. It’s about ideas.”

Related Material

Thornton Dial, Sr., African Jungle Picture: If the Ladies Had Knew the Snakes Wouldn't Bite Them They Wouldn't Have Hurt the Snakes; If the Snakes Had Knew the Ladies Wouldn't Hurt Them They Wouldn't Have Bit the Ladies,1989. Enamel, industrial sealing compound, wire on wood, 48 3/4 x 96 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of William Arnett, 1992.120

Thornton Dial, Sr., Life Go On, 1990. Oil on canvas, 96 x 71 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Ron and June Shelp, 1993.63

Thornton Dial often addresses political themes directly but not simplistically. Here, two paintings explore aspects of human conflict: violence and reconciliation. In the long title of the top artwork—African Jungle Picture: If the Ladies Had Knew the Snakes Wouldn't Bite Them They Wouldn't Have Hurt the Snakes; If the Snakes Had Knew the Ladies Wouldn't Hurt Them They Wouldn't Have Bit the Ladies—Dial explains how misconceptions can lead to violence. The curving snakes encircle the heads of several women, forming the outline of their hair. The snakes differentiate each figure, but they are also part of each one. In a similar composition in Life Go On, Dial painted two birds encircling what seems to be a female face. Instead of misunderstanding, this painting’s title suggests reconciliation or acceptance.

Michael Platt, Enough (from the New Orleans series), 2006. Digital pigment print, 37 x 25 1/8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Richard E. Brock, © 2006 Michael B. Platt, 2009.15.1

Like Thornton Dial, many African American artists have used their work to explore bewildering and sometimes devastating events that have directly affected their communities. In Enough, Michael Platt conveys the disorienting feeling many had upon returning to the Gulf region after the damage wrought by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The print recalls Platt’s walking in a once-familiar neighborhood after all the streets and other landmarks had been washed away. Platt made Enough amid fierce public debates about the number of African American residences destroyed by the storm and the efficacy of federal disaster support to black residents. The female figure, set among driftwood and other debris, is a poignant reminder of the isolation felt by those who lost their homes and communities.

Jules Allen, Untitled (police subduing man), (from the series Hats and Hat Nots), 1987. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 19 3/4 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the artist, © 1987 Jules Allen, 1994.62

The subject of urban conflict links this photo by Jules Allen and Dial’s Top of the Line (Steel). In this ironic picture, police pin down a man on a city street while smiling couples seem to gaze down from the cigarette advertisement on the wall. By including the billboard, Allen raises questions about how poverty and consumerism frame this disquieting scene.

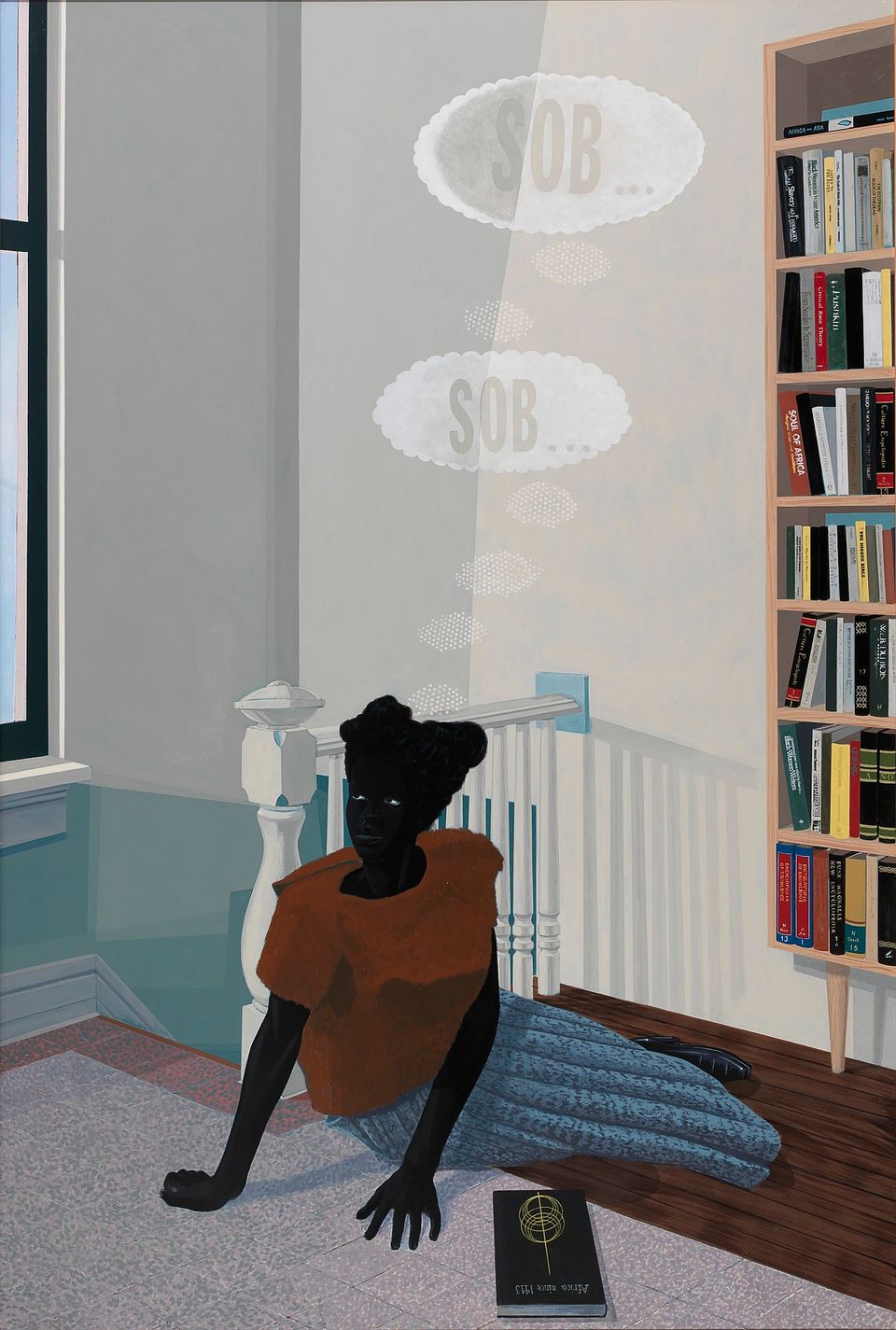

Kerry James Marshall, Sob Sob, 2003. Acrylic on fiberglass, 108 x 72 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, ©2003 Kerry James Marshall, 2010.29

Like Thornton Dial and Michael Platt, Kerry James Marshall's artwork also explores issues of race and identity which is deeply rooted in personal biography and historical detail. While interviewed for the PBS series Art21, Marshall explains: "You can't be born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955 and grow up in South Central [Los Angeles] near the Black Panthers headquarters and not feel like you've got some kind of social responsibility." Sob Sob is a painting about the accumulation and dissemination of knowledge, and relates closely to Marshall's ongoing exploration of African American history.

The painting depicts a female figure seated in front of a tall shelf of African history books. A volume titled Africa since 1413 lies at her feet as she gazes into the sunlit interior. It's unclear whether her contemplative gaze is one of wistful longing for a pre-colonial past or anguish over the transformation of the African continent that began in 1413 with European expeditionary missions. A thought bubble floating above the girl's head further complicates this emotional ambiguity. The text can be read as either a cry of despair or a pointed expression of anger.

To see—and hear—Kerry James Marshall for yourself, view an interview with him as part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Meet the Artist video series.