As the final speaker in this year's Clarice Smith Lecture Series, noted scholar Lawrence Weschler presented a talk on race relations in the United States, using Ed Kienholz's Five Car Stud as the mirror in which this difficult history is reflected and refracted. A life-size installation, Five Car Stud, is a powerful, haunting tableau: once you see it, you can't unsee it; it's that troubling and that strong.

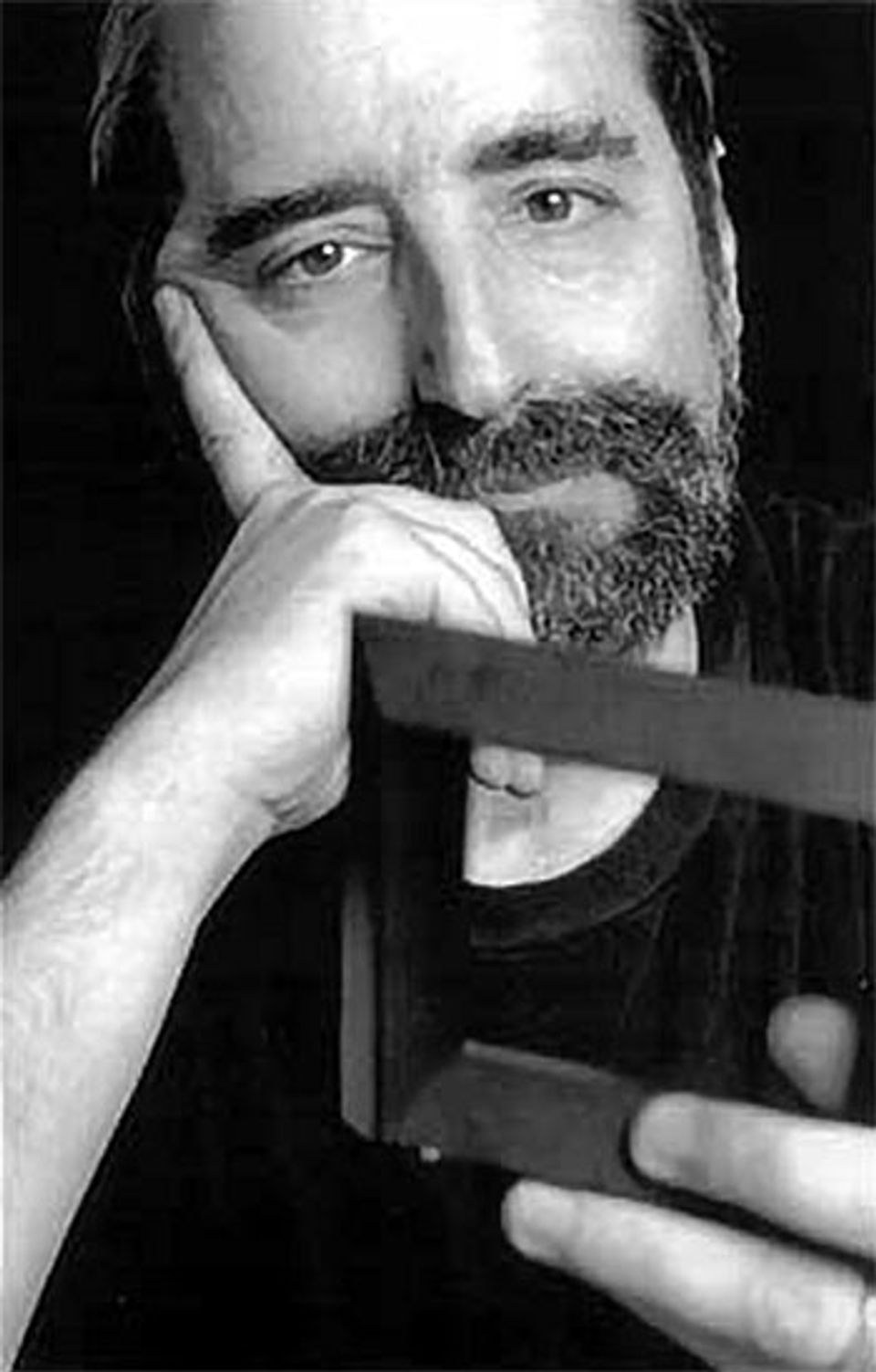

Lawrence Weschler met Kienholz years ago when he was contributing to an oral history of prominent artists working in Los Angeles in the 1960s and '70s. Weschler described Kienholz as "a frenemy...hilarious, generous, scary, mean-spirited and everything at once." Clearly, he knew how to push people's buttons, whether they were sitting across from him, or would one day come face-to-face with his artwork.

Born in Washington State in 1927 to a "difficult father and devout mother," Kienholz was raised on a wheat farm during the Depression. He became part of the art scene in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, and opened the Ferus Gallery with Walter Hopps, who would become a renowned curator at museums on both coasts, including the forerunner to SAAM, the Smithsonian's National Collection of Fine Arts and the Corcoran Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C. After a time, Kienholz left for Berlin, then divided his time between the German capital and Idaho.

According to Weschler, in 1968, Kienholz wanted to "do a take on race in a serious way." He created Five Car Stud using automobiles and life-size figures of men, one woman, and one child. As if this were a stage piece, the headlights give the work a feeling of theater: we've somehow become spectators who have come across this horrific scene. The work "impossible to show when it's finished," appeared in Documenta 5, the noted art fair held in Kassel, Germany in 1972. It was purchased by a foundation in Japan, and then something strange happened: the work disappeared for about forty years.

In 2011, it resurfaced and went on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. This became the artwork's first public viewing in the United States. Two generations since its creation, the work is as powerful—and unfortunately as relevant—as ever. "Art matters," Weschler reminded us near the end of his provocative talk, "Art provides occasions for serious thought."

Vistors to SAAM can see Sollie 17, the work Ed Kienholz created with his wife Nancy Reddin Kienholz, on view on the third floor of the museum. This piece addresses the themes of isolation and the emptiness of aging alone.

If you missed Weschler's talk, watch the webcast.