Born 1962 in Philadelphia, PA

Lives and works in Denver, CO

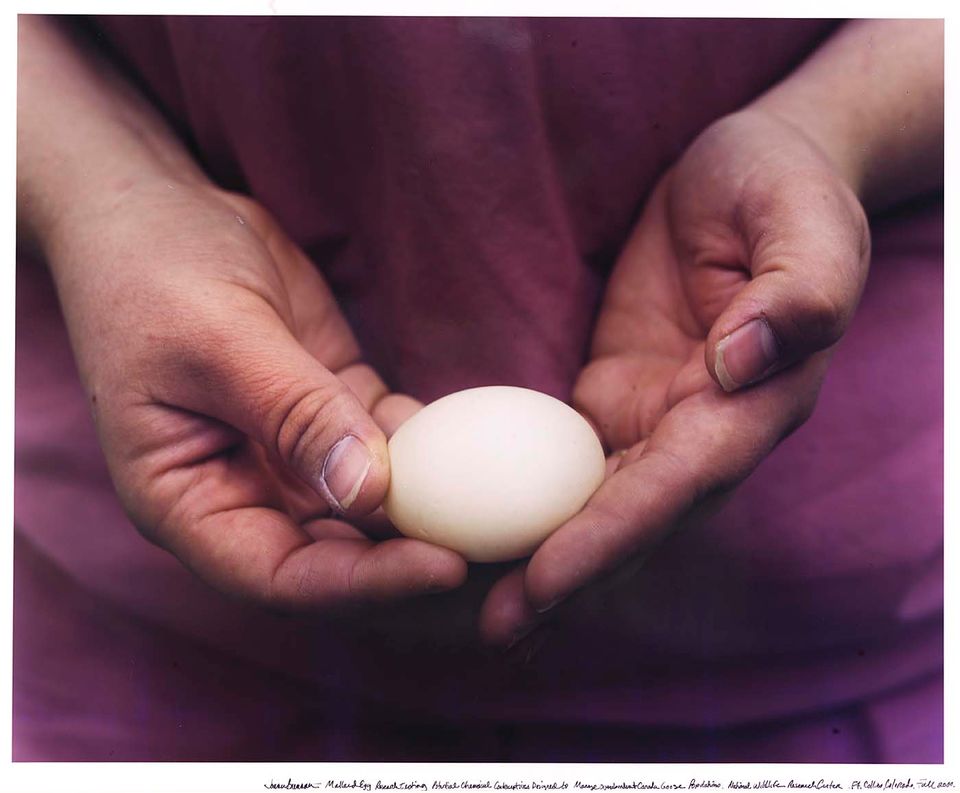

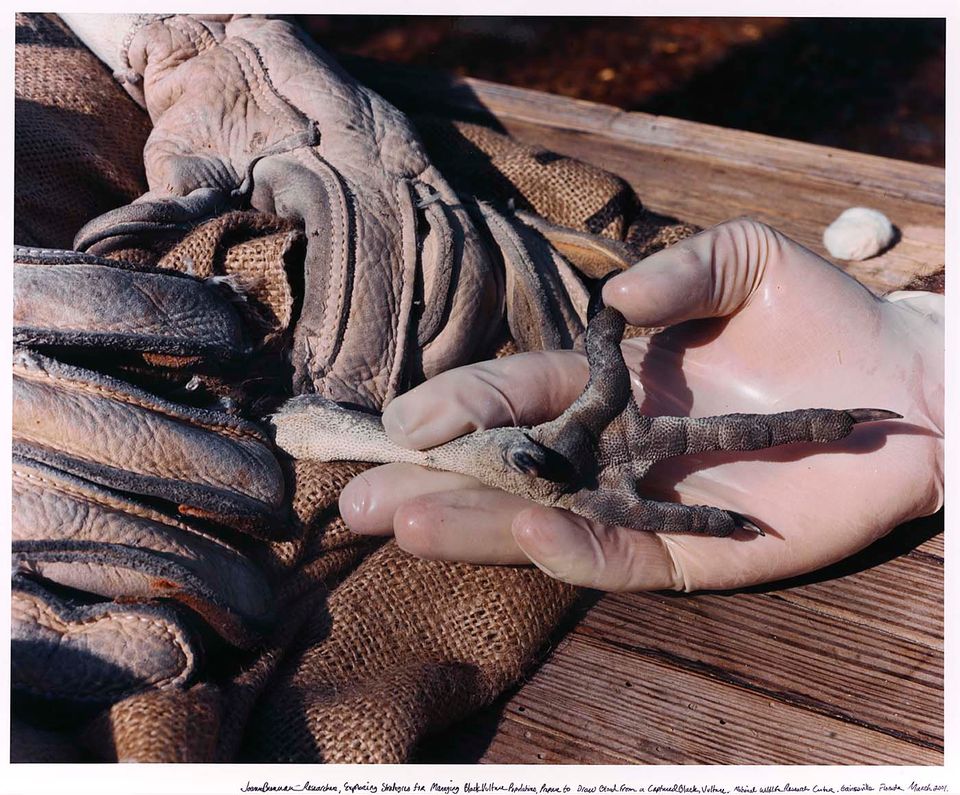

Joann Brennan’s photographs grapple with the question of how we sustain wildness in a human world. Her work recognizes the paradoxical nature of human efforts to control and conserve wildlife. In her Managing Eden series, Brennan captures stewardship efforts across the country, showing the intimate relationship between scientists and their specimens.