New Glass Now

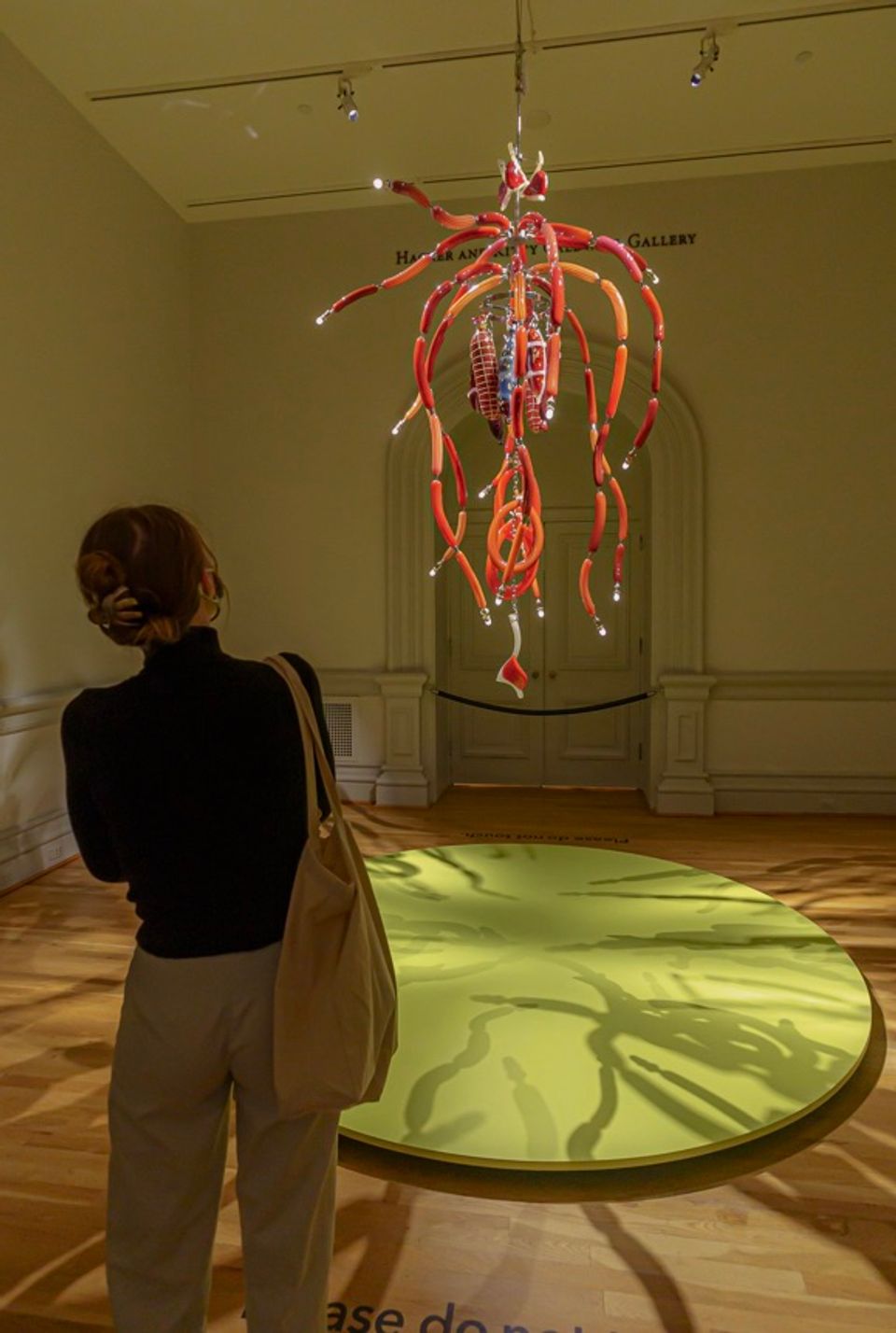

Deborah Czeresko, Meat Chandelier, 2018, blown glass, metal armature, 96.06"H x 59.84"W x 59.84"D, The Corning Museum of Glass, 2019.4.165; Photo by The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

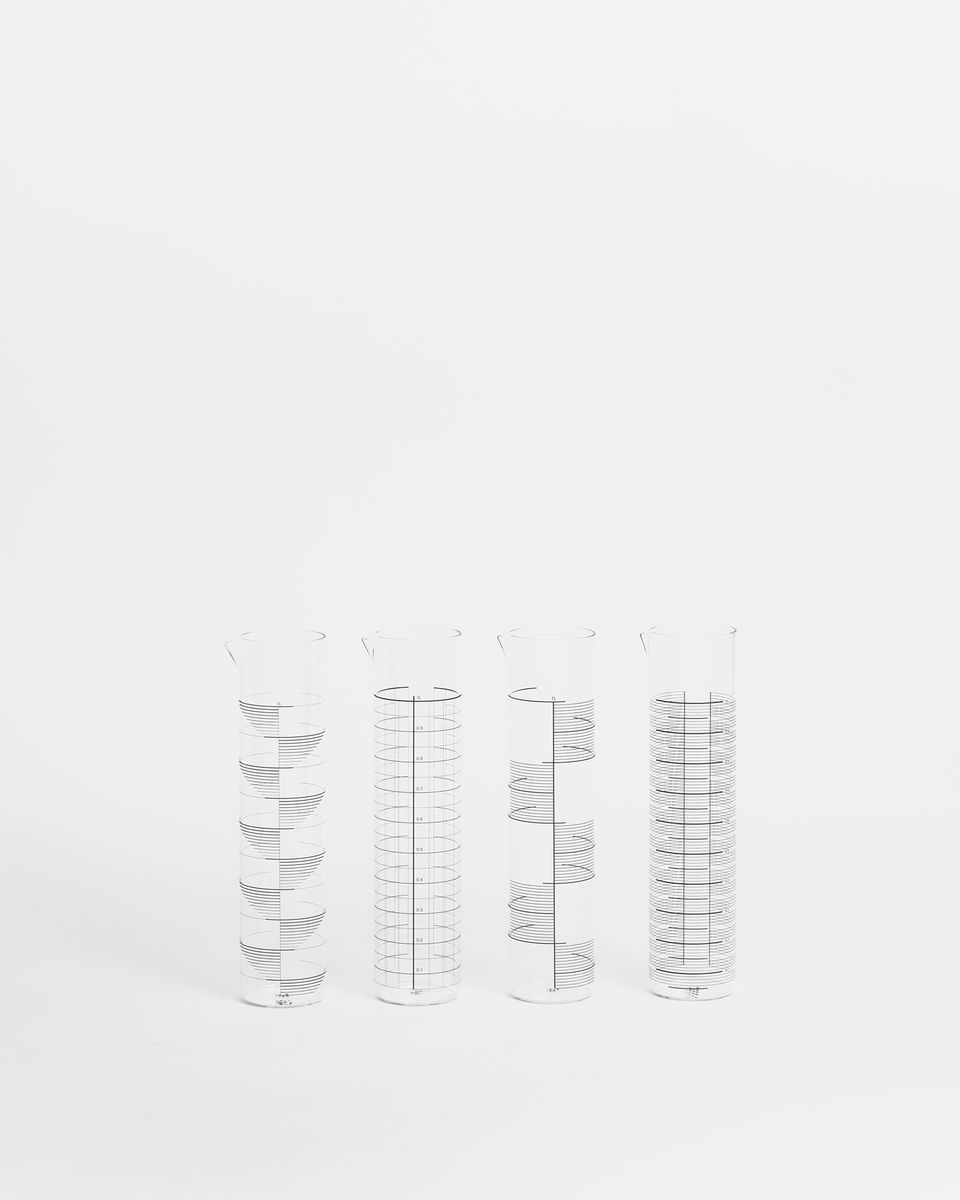

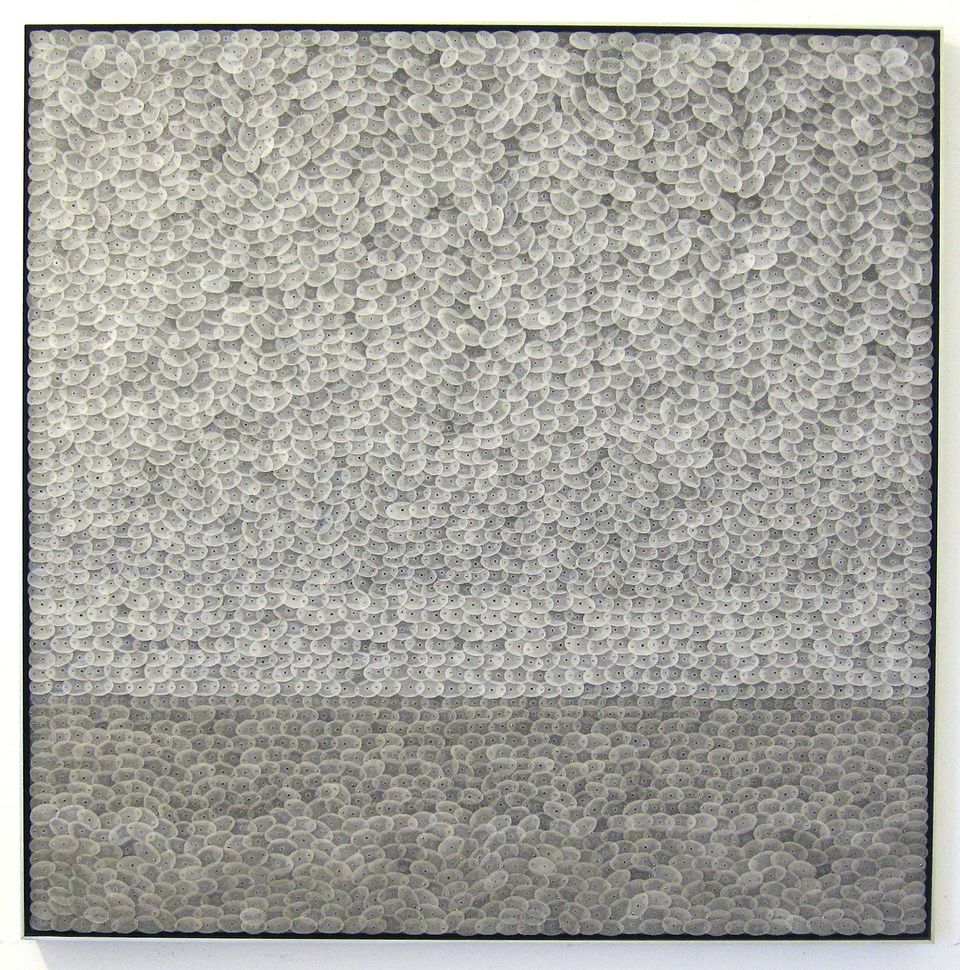

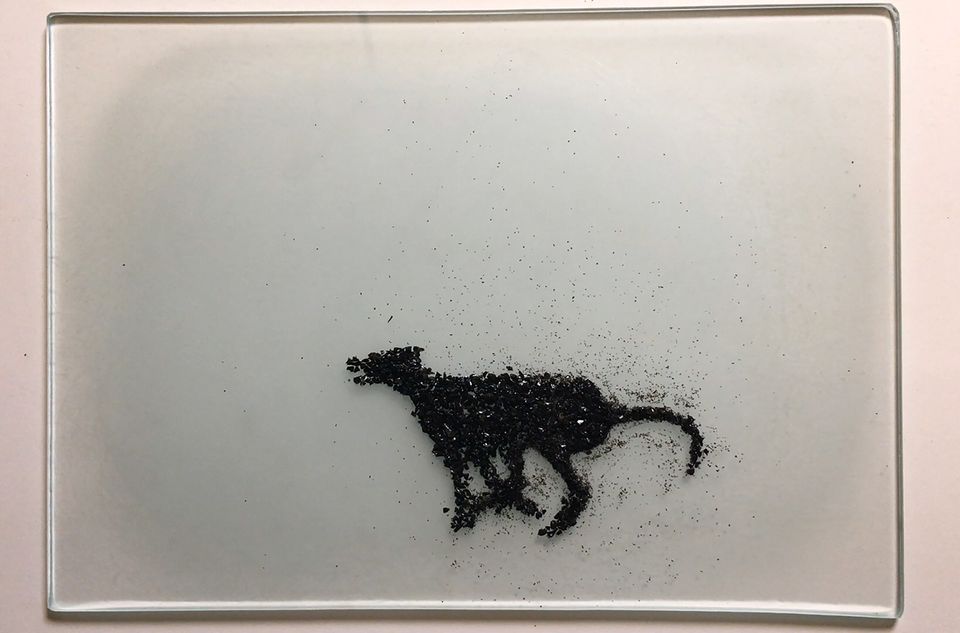

New Glass Now documents the innovation and dexterity of artists, designers, and architects from around the world working in the challenging material of glass.

This global survey is designed to highlight the breadth and depth of contemporary glass making. Its presentation at SAAM’s Renwick Gallery features objects, installations, videos, and performances made by fifty artists working in more than twenty-three countries. From technically masterful vessels to experiments in the chemistry of glass, these works challenge the very notion of what the material of glass is and what it can do.

Description

New Glass Now, organized by The Corning Museum of Glass, was curated by a panel of thinkers, makers, and writers and is the result of their varied perspectives and experiences. The artworks were selected by Aric Chen, curatorial director at Design Miami, and professor and director, curatorial lab, Tongji University; Beth Lipman, artist, Sheboygan Falls, Wisconsin; Susanne Jøker Johnsen, head of exhibitions at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture, Design, and Conservation; and Susie J. Silbert, curator of modern and contemporary glass at The Corning Museum of Glass.

In 2018, The Corning Museum of Glass issued an open call for submissions to artists and designers from around the world, asking for works made in the previous three years. Anyone working in glass could apply from the novice hobbyist to the most famous artists—all were given equal consideration. More than 1,400 individuals, collaborators, and companies submitted nearly 4,000 images of work. The Corning Museum of Glass then asked the curatorial panel to review and choose 100 artworks that best represented a diverse approach to glass working today.

New Glass Now is the third iteration of a groundbreaking exhibition series. The two prior exhibitions, Glass 1959 and New Glass: A Worldwide Survey in 1979, catalyzed major changes in the glass field. The Renwick Gallery hosted New Glass: A Worldwide Survey in 1980. Today, as the Renwick continues to keep with the pulse of contemporary glass in the United States, New Glass Now once again highlights the dynamic, global field as it is today.

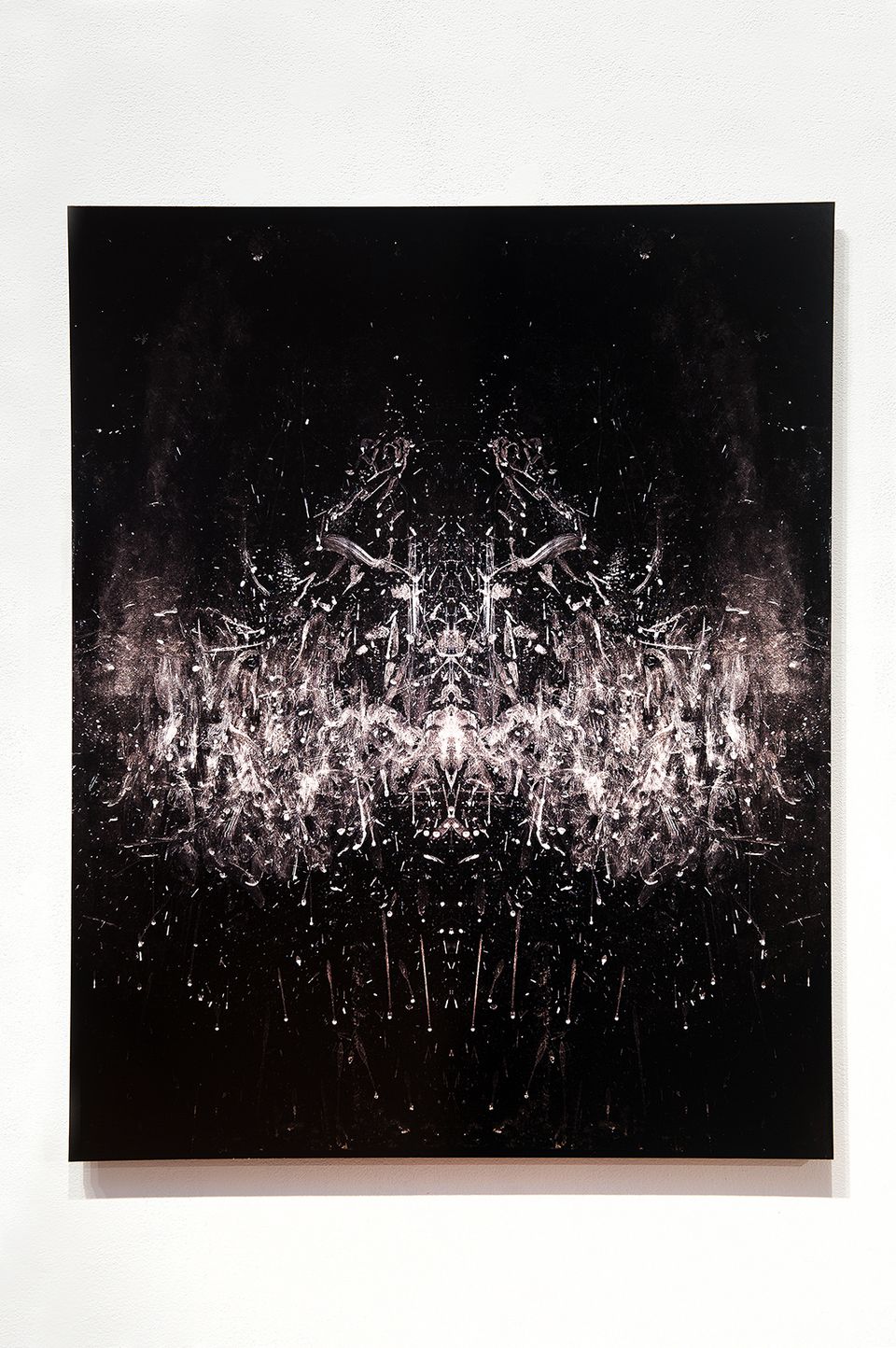

The presentation at the Renwick Gallery features artists who embody new voices, visions, and representation through glass, including American artists James Akers, Miya Ando, Dylan Brams, David Colton, Deborah Czeresko, Nickolaus Fruin, Sharyn O’Mara, Suzanne Peck, Austin Stern, Megan Stelljes, C. Matthew Szösz, Bohyun Yoon. The exhibition also features artworks by Tamás Ábel (Hungary), Kate Baker (Australia), Maria Bang Espersen (Denmark), Monica Bonvicini (Italy), Doris Darling (Austria), Nadege Desgenetez (France), Karen Donnellan (Ireland), Choi Keeryong (United Kingdom), Jitka Kolbe-Růžičková (Czech Republic), James Magagula (Kingdom of Eswatini), Fredrik Nielsen (Sweden), Aya Oki (Japan), Wang Qin (China), and Sylvie Vandehoucke (Belgium).

Visiting Information

Installation Images

Videos

Credit

New Glass Now has been organized by The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. The presentation at the Renwick Gallery is made possible by generous support from the Alturas Foundation, Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass, Crown Equipment Exhibitions Endowment, and Jacqueline B. Mars.

SAAM Stories