Artist

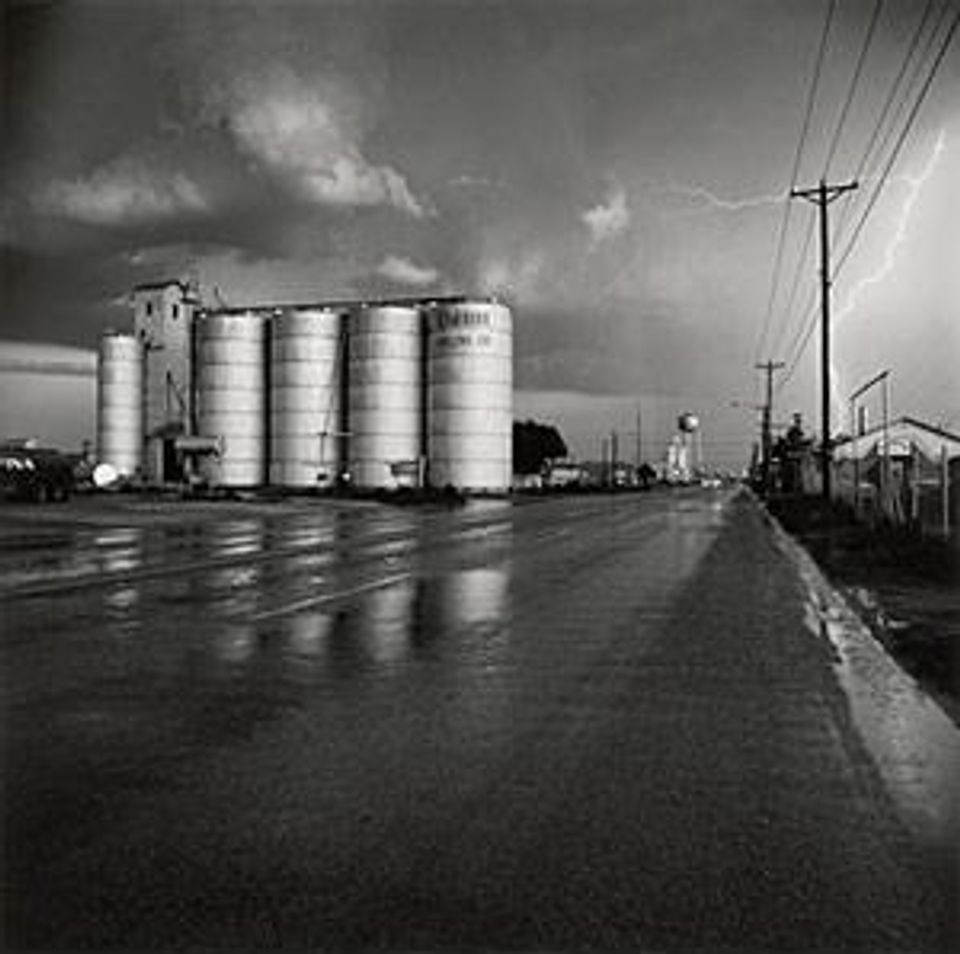

Frank Gohlke

born Wichita Falls, TX 1942

- Also known as

- Frank William Gohlke

- Born

- Wichita Falls, Texas, United States

- Active in

- Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

Videos

Exhibitions

November 27, 2008–March 3, 2009

For more than 30 years, Frank Gohlke (b. 1942), a leading figure in American landscape photography, has explored the ways Americans build their lives in a natural world that rarely fits within a traditional pastoral ideal.