Jacob Kainen

- Born

- Waterbury, Connecticut, United States

- Died

- Washington, District of Columbia, United States

- Active in

- Washington, District of Columbia, United States

- Chevy Chase, Maryland, United States

- New York, New York, United States

- Biography

Printmaker who worked in woodcut, silk screen, and other media; his style gradually evolved from the social realism of the 1930s to more abstract portraits in the 1950s and later.

Charles Sullivan, ed American Beauties: Women in Art and Literature (New York: Henry N. Abrams, Inc., in association with National Museum of American Art, 1993)

- Artist Biography

Jacob Kainen died in March [2001] at his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland, at the age of ninety-one. During our twenty-five years of friendship, I came to view his life and his art as inextricably intertwined. Kainen's extraordinary intelligence and his deeply felt passions are likewise inseparable. His complex vision is vividly apparent in the many hundreds of paintings on canvas and paper he produced and in his important body of drawings and prints that span more than seventy years.

Kainen devoted most of his time over several decades to scholarship, curatorial work, and the encouragment of younger artists that Avis Berman describes in her accompanying tribute. During those years, he confined his creative efforts to nights and weekends. The vast number of paintings and works on paper that he completed under these circumstances is nothing less than astonishing. It is a legacy that confirms the notion that a painter finds time to paint regardless of life's demands.

In addition to art, Kainen was keenly interested in politics, music, literature (especially poetry), and philosophy. His immense curiosity enlivened his art, as it did his writings, lectures, and the informal conversations we had in his studio on a regular basis over two decades. Kainen began his life as an artist in New York during the 1930s. In his early paintings, his varied intellectual concerns were somewhat overt. As a response to the economic hardship and unrest of the period, his pictures embraced political and social concerns. Many of his canvases depict disasters: Tenement Fire and Disaster at Sea (both 1934), Flood (1935), and Invasion (1936). Others record moments in daily life: Cafeteria (1935), Hot Dog Cart and Oil Cloth Vendor I (both 1937) and Barber Shop (1939). In Kainen's later abstract work, his social and philosophical concerns were less obvious.

Kainen's self-education in museums and libraries, where he studied the work of Rembrandt, Diego Velázquez, John Constable, and Paul Cézanne, among others, had a more profound influence on his art than his early classes at the Art Students League and Pratt Institute. From the beginning, his paintings were both dramatic and romantic, revealing not only his knowledge of these earlier masters, but also a keen awareness of twentieth-century expressionism, especially in Europe but also in America. He was familiar with the art of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Edvard Munch, as well as the work of George Bellows and John Sloan.

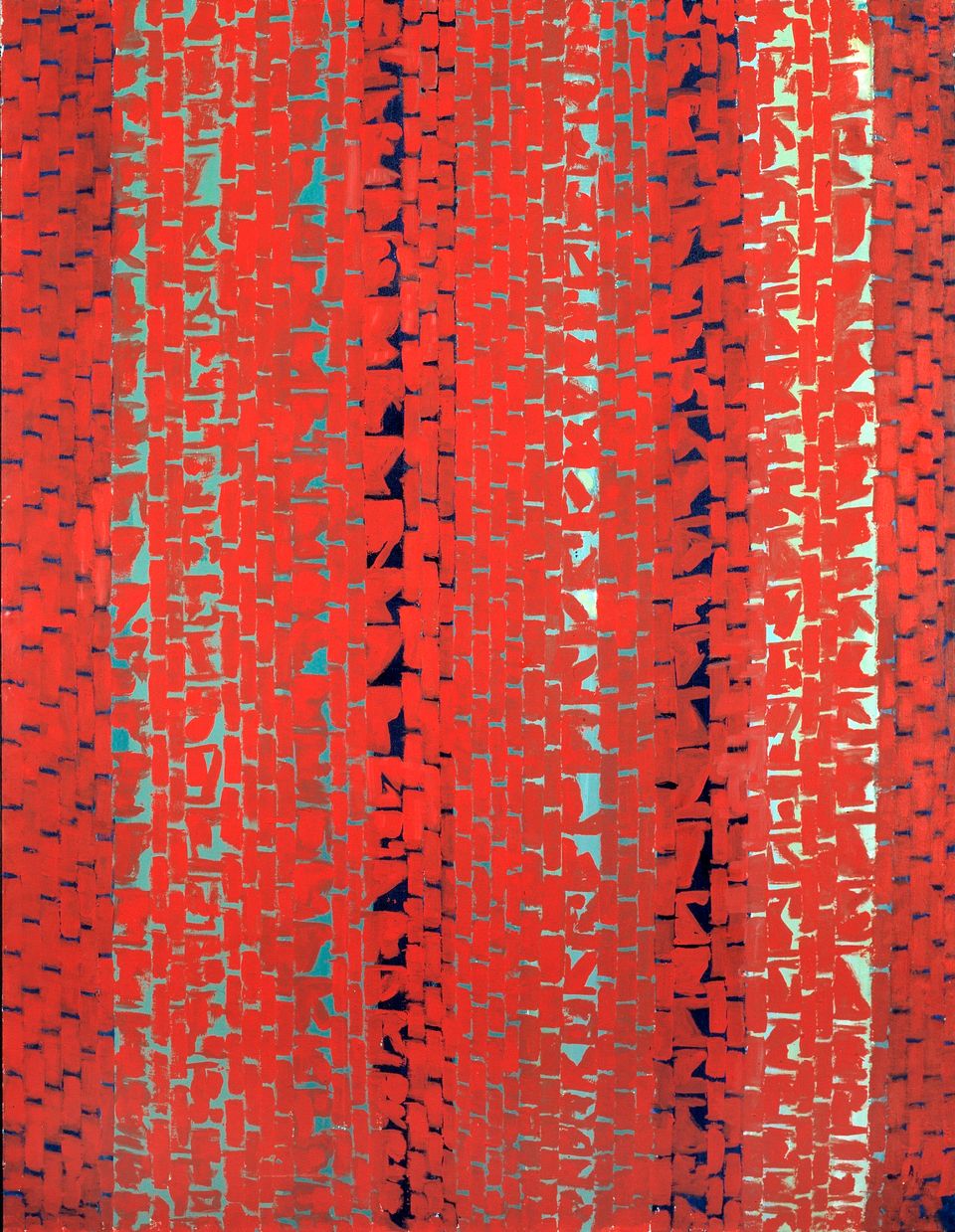

Interlocking shapes, layered forms, and strong gestures mark his early paintings, and suggest aspects of the abstract work that followed. The color world that Kainen created in the 1930s is prescient of the extraordinary subtlety that became a hallmark of his mature abstractions. The muted tones of his early canvases contrast greatly with the brilliant colors of his later ones. In both early and late work, however, he juxtaposed hues that could never be found on any paint manufacturer's color chart; instead, he lovingly mixed paint from various tubes to create new colors that he then applied in layers. Thus he created a rich surface pulsation that pervades not only his canvases and paintings on paper but also his late color woodcuts.

In New York Kainen forged close friendships with some of the city's most forward-looking artists, including John Graham, Arshile Gorky, and Stuart Davis, all of whom were examining abstraction. In 1942 he left New York to assume a curatorial position at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and explored his new home through his art. Kainen's interest in abstraction shines through such Washington street scenes as Street Corner with Red Door (1947) and Clock Tower (1948). By 1949, abstraction, frequently peppered with referential elements such as figures and trees, became ascendant in Kainen's approach. The titles of works such as Magician (1951) suggest figurative motifs, whereas titles like The Coming of Surprise (1951) hint at metaphysical, nonfigural themes.

This focus on abstraction ended around 1957, when his imagination was again fired by representation. The essential facture of his work, however, had undergone radical changes during his exploration of abstraction; Kainen's new approach to representation incorporated these painterly effects. He enhanced color shapes by overpainting them, and they took on a life apart from and of equal importance to their representational function. The figure—both nude and clothed—was the primary subject of this phase of Kainen's work. The paintings of Kirchner and Henri Matisse may have served as inspiration for Kainen's Crimson Nude (1961) in its subject matter and use of dynamic color and richly gestural paint handling. Portraits of artist friends in his Washington circle occupied him as well during these years. In Gene Davis (1961) vertical stripes, which marked Davis's signature style, envelop the artist. The Shannons (1964) shows painter Joseph Shannon with his arm wrapped around his wife, who carries their small child in her folded arms.

Kainen returned to a lyrical, generally high-keyed abstraction by the close of the 1960s. His firm commitment to this direction in his art corresponded with his marriage to Ruth Cole in 1969 and his retirement from his curatorial position a year later. Ruth Kainen's dedication to him and his work would have been reason enough for the buoyant spirits that sparked Kainen's work for the rest of his life. For a brief time, his forms became fairly hard-edged, his fields of color relatively unmodulated. But by 1972, the pulsation of form and color that had previously been central to his art—both figurative and abstract—regained dominance, never again to be abandoned.

Jacob Kainen died while preparing to go to his studio. He had continued to examine the painterly process in all of its aspects—color, gesture, and form—until the very end of his life. He began Broken Arc, for example, when he was eighty-five and completed it three years later. Its shimmering color and gracefully fluid shapes and its tension between geometry and nature summarize many of Kainen's preoccupations throughout his career. Suggestive of youthful energy, its true accomplishment is in fusing extemporaneity with the experience and wisdom acquired over a long, immensely productive life.

Ruth Fine "Appreciation: The Art of Jacob Kainen." American Art journal 15, no. 3 (fall 2001), pp. 90–93

Luce Artist BiographyJacob Kainen moved to New York at a young age and began studying drawing at the Art Students League, the Pratt Institute School of Art, and the New York University School of Architecture. In the 1930s, he began his career as a social realist painter because of his strong interest in conveying the human experience. He later abandoned this style in favor of abstract expressionism, and became friends with fellow painter Arshile Gorky. In 1942, Kainen joined the Smithsonian as an aide with the Division of Graphic Arts at the U.S. National Museum (now the National Museum of American History) and by 1946 was appointed curator. Later, in 1966, he served as a curator of graphic arts at the Smithsonian's National Collection of Fine Arts (now the American Art Museum), where he expanded the collection of modern American prints and drawings. Until his retirement from the Smithsonian in 1970, Kainen spent his days researching at the Museum and dedicated his evenings to studio work.