An expanded presentation of the now iconic Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly (aka The Throne) by James Hampton is currently on view in the newly installed and reimagined galleries for folk and self-taught art at SAAM. Created during a period of about fourteen years, and representing Hampton's total known artistic output, Hampton created the throne in response to several religious visions that prompted him to prepare for Christ's return to earth.

Anticipating the second coming, he created a visionary installation, assembling an altar-like throne with found objects from his work in a federal office building and his Shaw neighborhood in Washington, DC, including burned-out light bulbs, discarded furniture, old desk blotters, and empty jelly jars. He covered many of the elements with salvaged silver and gold foil, and put it all together in a carriage house he rented near the boarding house where he lived.

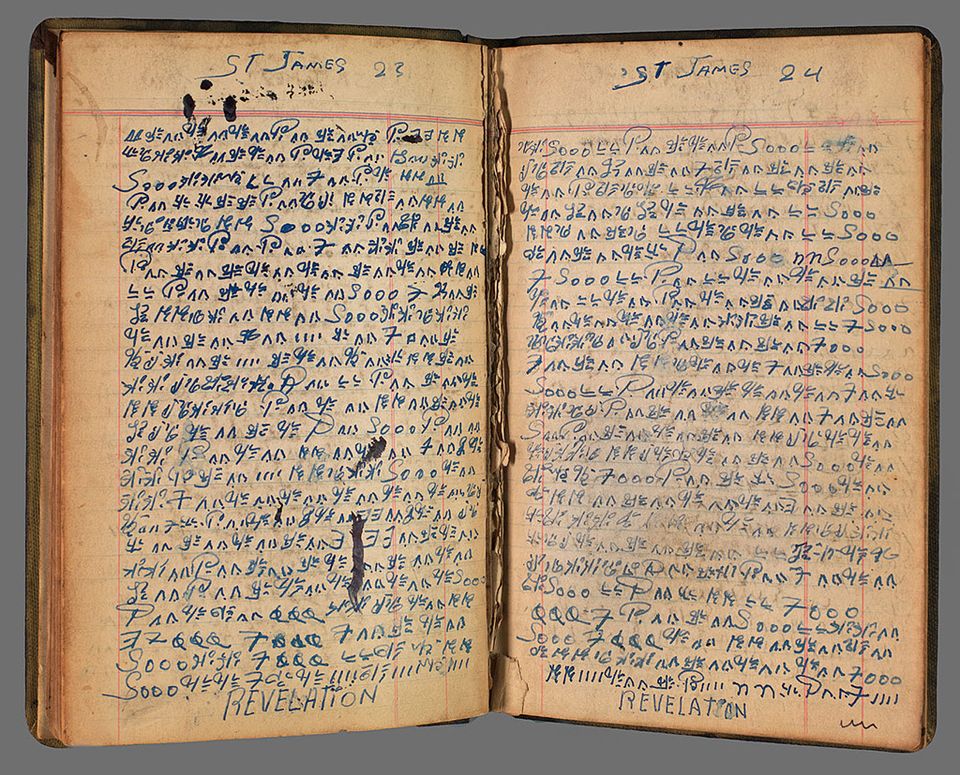

Hampton made over 180 individual elements for his installation, which vary in size, detail, and state of finish. The current larger configuration of the throne includes two items that are on view for the first time: a chalkboard showing some of Hampton's sketches or working plans for the throne and a small book he kept, written primarily in an invented or "asemic" script, meaning it is unreadable or lacking specific semantic content. Hampton referred to himself as "Director, special projects for the state of eternity," as well as "Saint James," an echo of Saint John who was divinely instructed to record his vision of the second coming in a secret script in a small book.

Hampton, too, felt he was divinely inspired in his writing and the creation of the throne. He may have believed his arcane "spiritual" script to be the result of communication with a higher being—the word of God as received by him. "It's an enigmatic book," says Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at SAAM, "but it gives us insight into how much he wanted to fulfill this role and be present if this event he believed in was going to happen."

Over the years, a handful of people including scholars and art historians have tried to decode Hampton's writing, but nobody has succeeded. It seems he invented his own language. This may have been a conscious act or a symbolic transcription of his visions. Another possibility is that he wrote it in a spiritually-induced trance, that it is a "spirit script," or automatic writing akin to glossographia (a graphic variation of glossolalia) or "writing in tongues." Hampton's writing, however, seems more measured and controlled than that which would have been written by somebody in an ecstatic state.

Though Hampton's writing remains a mystery, when we're standing in front of the throne, our eye gradually fixes on the reassuring words he attached to the top in silver foil, "Fear Not."