Santos de palo ( wooden saints) are Roman Catholic devotional figures used in churches and private homes. Individuals pray to these sacred figures as vehicles of God to assist in life’s difficulties. The tradition of Puerto Rican santos is rooted in Spanish, Taíno, and African traditions and continues to this day. Typically, these wooden figures are carved in frontal poses, either seated or standing, and depict saints and biblical figures. Over time, santos were incorporated into Puerto Rican religious practices, community festivities, and national identity.

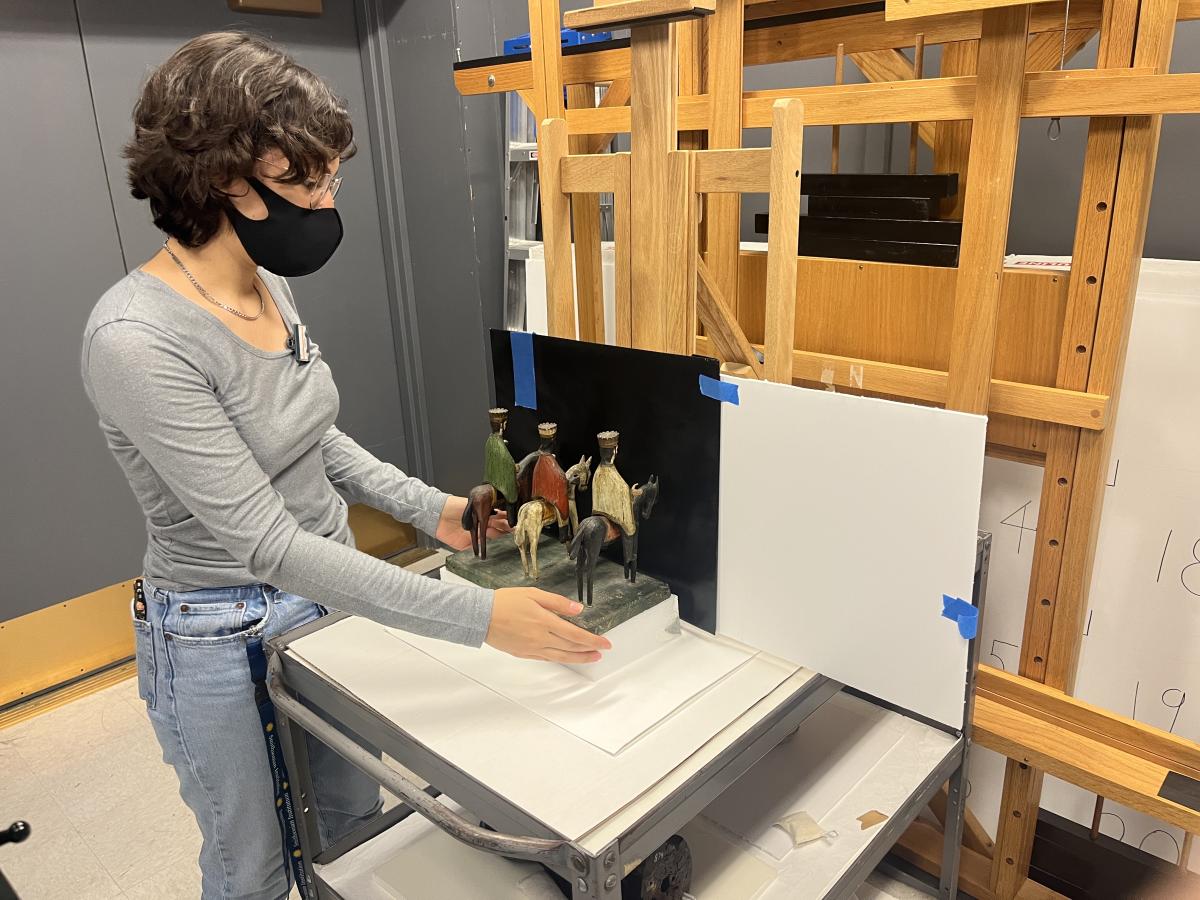

In the 1750s, a stylistic shift occurred from the earlier, more detailed, and realistic Spanish-inspired santos, to a more stylized and distinctly Puerto Rican style that included exaggerated anatomical proportions to echo the characteristics attributed to the saint. The two santos I studied reflect this interesting shift from a Spanish-inspired style to a regional Puerto Rican style. I joined SAAM’s Lunder Conservation Center as an undergraduate intern through the Smithsonian's Latino Museum Studies Program, and worked with members of SAAM's conservation team to use non-destructive analytical techniques to uncover layers of history through a comparative analysis of the two santos, created roughly 200 years apart.

Both santos are part of the Teodoro Vidal Collection at SAAM. Vidal was a Puerto Rican art collector, author, and self-taught historian who donated part of his remarkable collection to the museum in 1996. The older santo is currently cataloged as Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) and was created between 1675 and 1725. With the figure’s face upwards and her hands clasped in grief, she represents the moment Mary learns her son would die for the sins of mankind. Although this object doesn’t depict it, the iconography of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores usually includes a dagger piercing her heart to symbolize her grief.

After further researching the iconography of santos, I determined the original attribution to Nuestra Señora de los Dolores may be incorrect, and she may instead represent La Soledad (Our Lady of Solitude). Although the two santos have similar appearances, La Soledad is distinct from Nuestra Señora de los Dolores. La Soledad represents Mary on Holy Saturday, after the Crucifixion and before the Resurrection of her son. She is typically depicted as a solitary woman in mourning, her hands folded in prayer and her face upwards in grief, just like this santo. While I remain unsure of the figure's identity, the object nonetheless represents an example of early Puerto Rican santos with noticeable European influence, as seen in the s-curved Contrapposto pose, detailed swirling folds of the robe, an emotional gaze, and the overall naturalism of the figure.

The second santo I studied, San Miguel en Lucha con el Demonio (Saint Michael Fighting the Demon), was carved by a known artist, Francisco Rivera, who was popularly known as "Pancho el Santero," and was made sometime between 1850 and 1910. The image of San Miguel was used to ask for relief from an ailment or the humiliation of enemies. This San Miguel is portrayed as a youthful knight, dressed in armor, and equipped with a sword. He is standing confidently atop a lizard-like demon with bulging round eyes and protruding teeth lying helplessly across a stone. San Miguel extends his sword high in victory, and his other hand, now empty, likely would have held a scale, a traditional accessory of San Miguel, who decides the fate of souls by weighing them. San Miguel and the demon both exemplify the simplified, miniaturized proportions, and almost cartoonish figural rendering that characterizes later Puerto Rican santos. The visual differences between these two santos represent the gradual anatomical distortion as Puerto Rican artists began to create softer, simpler designs.

Construction of the Santos

While the stylistic appearance of the santos taught us a lot about them, I also wanted to learn about their material components and construction. To do that, we first used x-radiography to look inside the santos, similar to how a doctor examines broken bones. X-radiography tells us about the relative densities of different materials, and can provide conservators insights into an artwork's construction, past treatments, and current condition.

The x-radiograph of San Miguel highlighted how he was constructed from many pieces of wood secured with metal nails. The nails stand out because they are denser than wood, so they show up bright white in the x-radiograph. There is a clear separation of wood in the figure's right arm between the shoulder and elbow; the lack of nails or pegs suggests this arm was likely attached with an adhesive instead of nails.

In contrast, the x-radiograph of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores showed that she was carved from one piece of wood. Also visible is a large triangular shape in the back of her torso. This area is more radio-opaque compared to the surrounding wood, so it was likely filled during a later restoration with plaster, chalk, or another dense material.

Flaking Paint Layers

One of the most intriguing aspects of many Puerto Rican santos is their complex layers of paint. Traditionally, santos were repainted numerous times over their lives as an act of care, respect, and worship. Cleaning and repair of santos was often done on the evening before a feast day or as thanks for good fortune.

Technical imaging is an especially helpful means to observe and characterize paint layers. Technical imaging utilizes modified cameras and specialized imaging equipment to capture how different materials absorb and reflect various wavelengths of light, which can help characterize materials and highlight methods of construction, past alterations, and condition.

One of these techniques is ultra-violet (UV) induced visible fluorescence, which captures the visible fluorescence induced by UV radiation, which is just below 400 nm on the electromagnetic spectrum, basically how you see something glow under a black light! UV radiation can help us characterize different types of pigments and coatings and help differentiate layers of retouching.

The two images above show how older paint layers fluoresce while more recent areas of retouching appear dark. This difference is especially noticeable in the face of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores; showing how highly retouched her face is in comparison to San Miguel. These layers of retouching were also highlighted in x-radiographs, due to the different densities of the pigments used in each layer. The bright, orange-colored fluorescence of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores’ veil suggests the figure may be coated in a layer of shellac, which has this characteristic fluorescence under UV radiation.

X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (XRF)

Another non-destructive analytical technique commonly used by conservators is x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). XRF is used for elemental analysis and works well for identifying metallic elements like iron, lead, and copper. For painted surfaces, this can be useful in identifying pigments. Every element has a unique construction of atoms that are excited by x-rays in specific ways. An XRF unit shoots a beam of x-rays at a tiny area on an artwork, and the reaction of the elements in that area to the x-rays is then detected by the XRF unit and translated into a spectrum which conservators use to learn which elements are present.

One of the most eye-catching aspects of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores is the highlights on her mantle, which appear to the naked eye to be gold! The XRF data identified calcium, iron, potassium, traces of lead and copper, and confirmed the presence of gold! The traces of gold on Nuestra Señora de los Dolores attest to her prestige and importance.

XRF was also used on both the santos’ faces because technical imaging produced some particularly intriguing images. XRF identified lead along much of the face of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, which is supported by the appearance of her face in the x-radiograph, which looks bright white and radio-opaque (lead is very dense). The presence of lead is likely indicative of the use of lead white, which would have been a popular white paint during the time of her manufacture. On the other hand, zinc was detected on the face of San Miguel, which likely indicates the use of zinc white, a pigment which wasn’t widely used until the mid-19th century.

The mysterious fill material along the triangular shaped loss along the back of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores was covered in a layer of black paint, but the x-radiograph shows the fill material as denser than the surrounding wood. XRF indicated the presence of calcium, so the fill is likely comprised, at least in part, of calcium carbonate. Why this loss occurred, or why the fill was done, though, remains unknown.

Santos are a fascinating aspect of Puerto Rican art history; the two figures I studied represent how the style and construction of santos changed over time through the uniquely Puerto Rican combination of multiple cultural traditions. As a Latina, I am proud to be a part of the preservation of Latinx cultural heritage and material culture. Guidance from SAAM’s staff and learning about the critical responsibilities of conservators confirmed my passion for conservation and cultural heritage preservation. I encourage visitors to experience the Vidal collection at SAAM, as these are only two of the many spectacular examples of the richness of Puerto Rican art in the collection.

Former intern at SAAM's Lunder Conservation Center, Briana Teran came to the museum as a junior at New Mexico State University through the Smithsonian’s Latino Museum Studies Program, dedicated to increasing representation and documentation of the Latinx cultural experience within the museum field.