In 2022, SAAM acquired two new, large-scale photographic works by contemporary artist, professor, and rogue archivist, Stephanie Syjuco. Both artworks draw from the artist’s own research photographs taken in the Smithsonian archives, during her time as a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow (SARF) in 2019-2020. As a SARF fellow, Syjuco spent hours mining the vast archives of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and National Anthropological Archives, seeking out photographic material relating to Filipinx and Filipinx Americans. Born in the Philippines in 1974, Syjuco’s work critically addresses the absences and failings of institutional archives that hold material on or related to the Filipinx American experience.

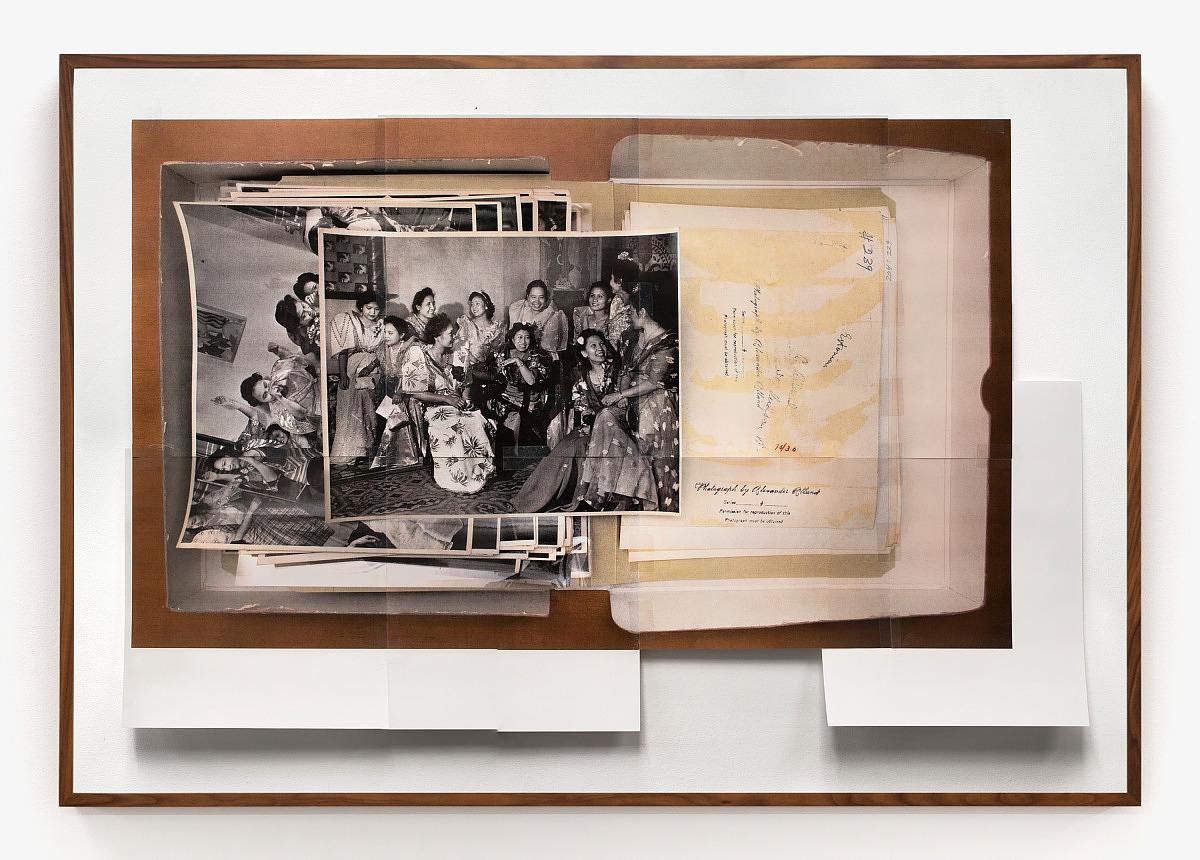

The two works SAAM acquired are representative of Syjuco’s innovative process of photographing original archival material, such as existing photographs, documents and ephemera, then enlarging and printing the images and physically reassembling them in her studio, before rephotographing them to create her final composition. In 2019, while at the National Museum of American History, Syjuco examined a box of photographs by the early twentieth century photographer and immigrant rights advocate, Alexander Alland Sr. In the 1930s, Alland, who was an active member of the New York Photo League, became known for his intimate portrayals of the life of immigrants in New York City. This work was published in Alland’s now largely forgotten 1943 book, American Counterpoint. Among Alland’s photographs, Syjuco unearthed images of a group of Filipina women posed in native dress, smiling and laughing in a finely decorated room.

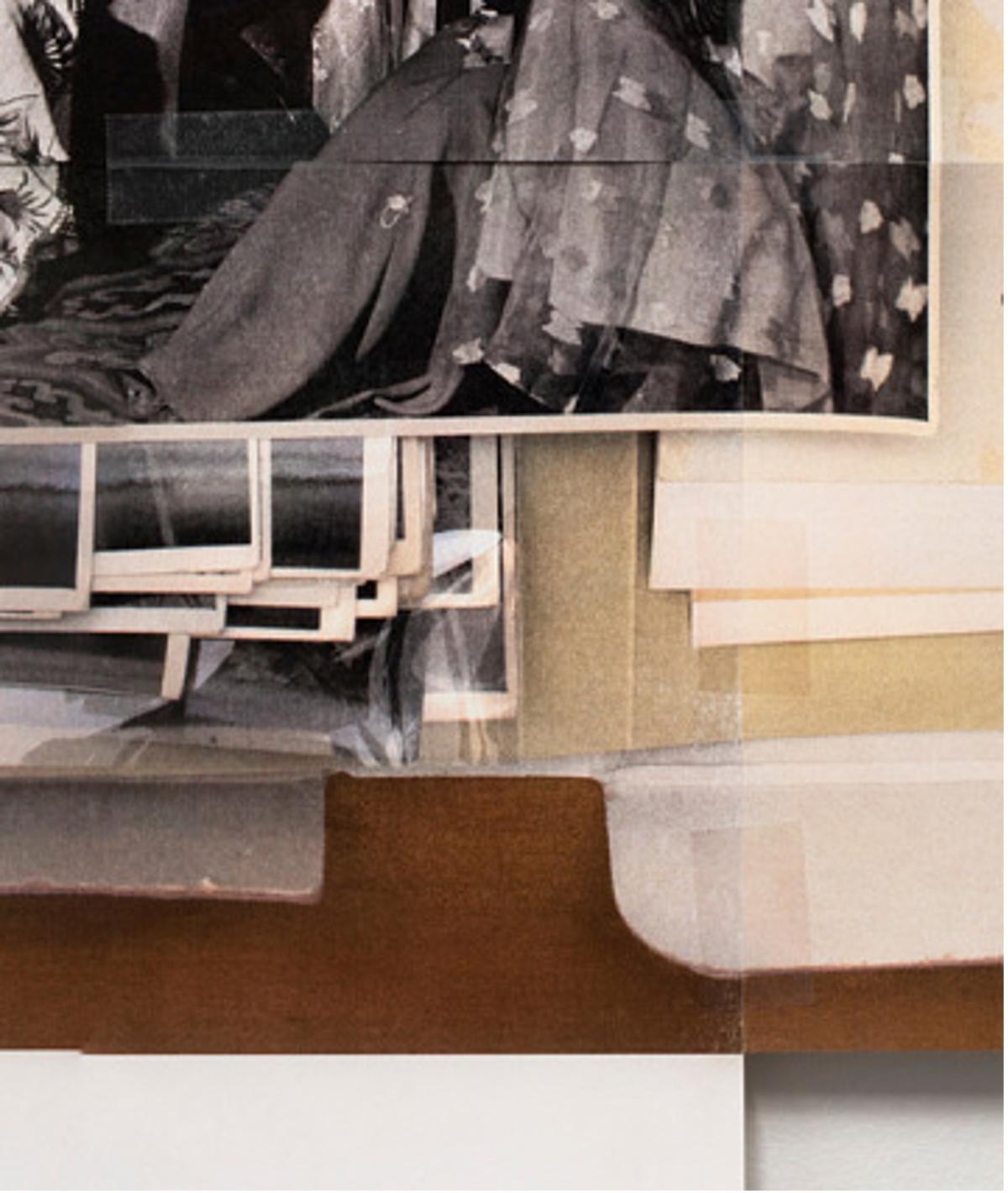

In her work, Nationalities: Eleven Filipino women in native dress (from the American Counterpoint project, Alexander Alland, Sr., Photoprints, circa 1940, National Museum of American History, Archives Center, NMAH.AC.0204), Syjuco rephotographs Alland’s images of the women confined inside the archival folder and box to which they have been relegated. In the detail below, tape is visible that the artist used to assemble the printed out images, before the final composition is produced as a single high resolution, large scale print.

Her process of taking and “piecing together” photographic images underscores the problematic function of archives, which by their nature obscure and conceal the objects contained within. The artwork’s lengthy title unambiguously includes the name of the archive and institution where the images are held, as well as the collection id number. By identifying the specific location and title of the archive, Syjuco draws attention to the layered and nearly hidden existence of images within a cavernous institution, such as the Smithsonian.

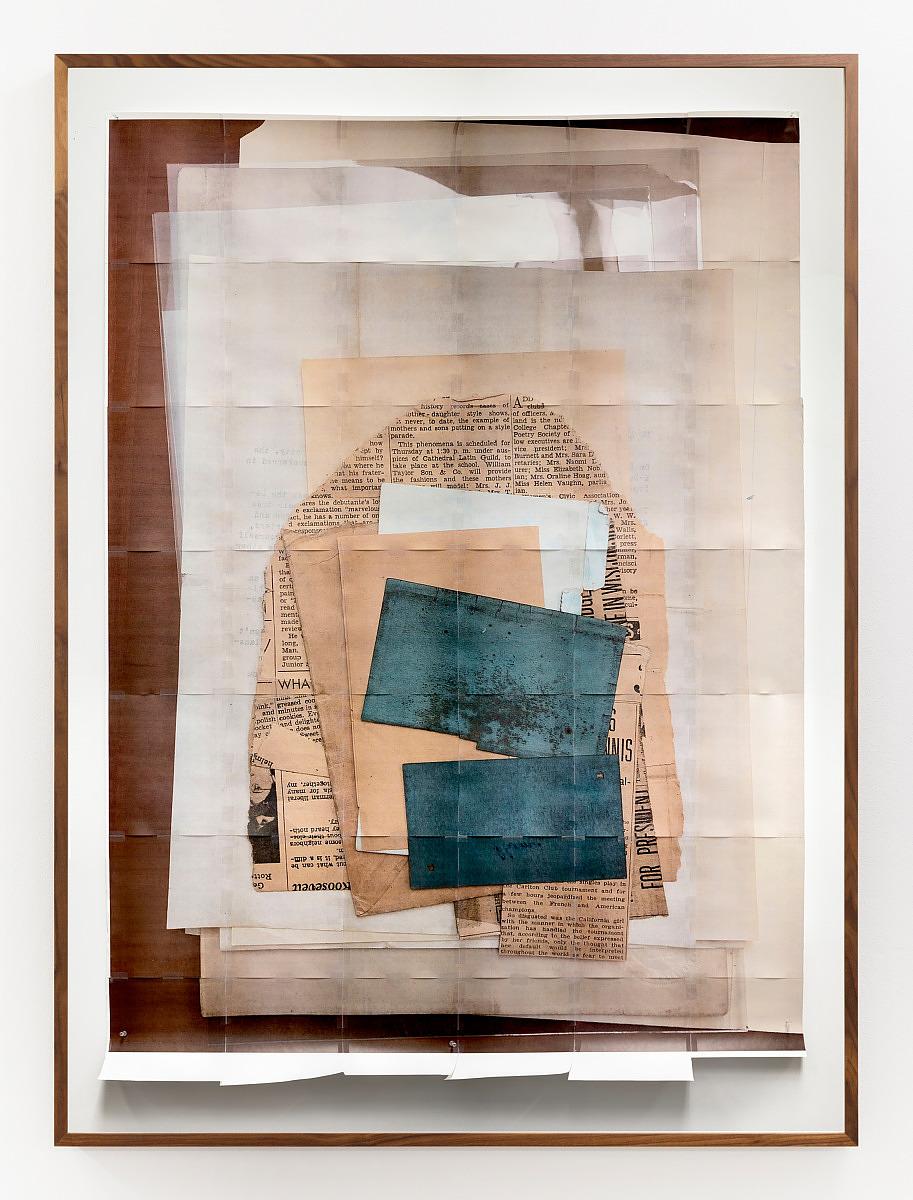

While searching for the hidden visual narratives of colonialism and American empire at the Smithsonian, Syjuco stumbled upon a disquieting file of documents belonging to an Ohio chapter of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in the 1950s. Her work, Reverse View: KKK (from Warshaw Collection of Business Americana Subject Categories: Ku-Klux-Klan, circa 1950s, National Museum of American History, Archives Center, NMAH.AC.0060.S01.01.KKK) (2021), is a meditation on her discovery and the process of reading the documents of this white supremacist hate group. The file was found in the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, an archive of American business ephemera also located at the National Museum of American History. Syjuco found it wedged between two folders with the innocuous topics “Ladies Clothes” and “Kitchen Appliances.” After reading each document, Syjuco turned the pages face down in the file and then photographed the pile of overturned ephemera, disallowing their words to be visible in her rephotographed image. The file itself is a prime example of the dormant violence that remains embedded within institutional archives and collections – part of the enduring violent history that Syjuco’s work addresses.

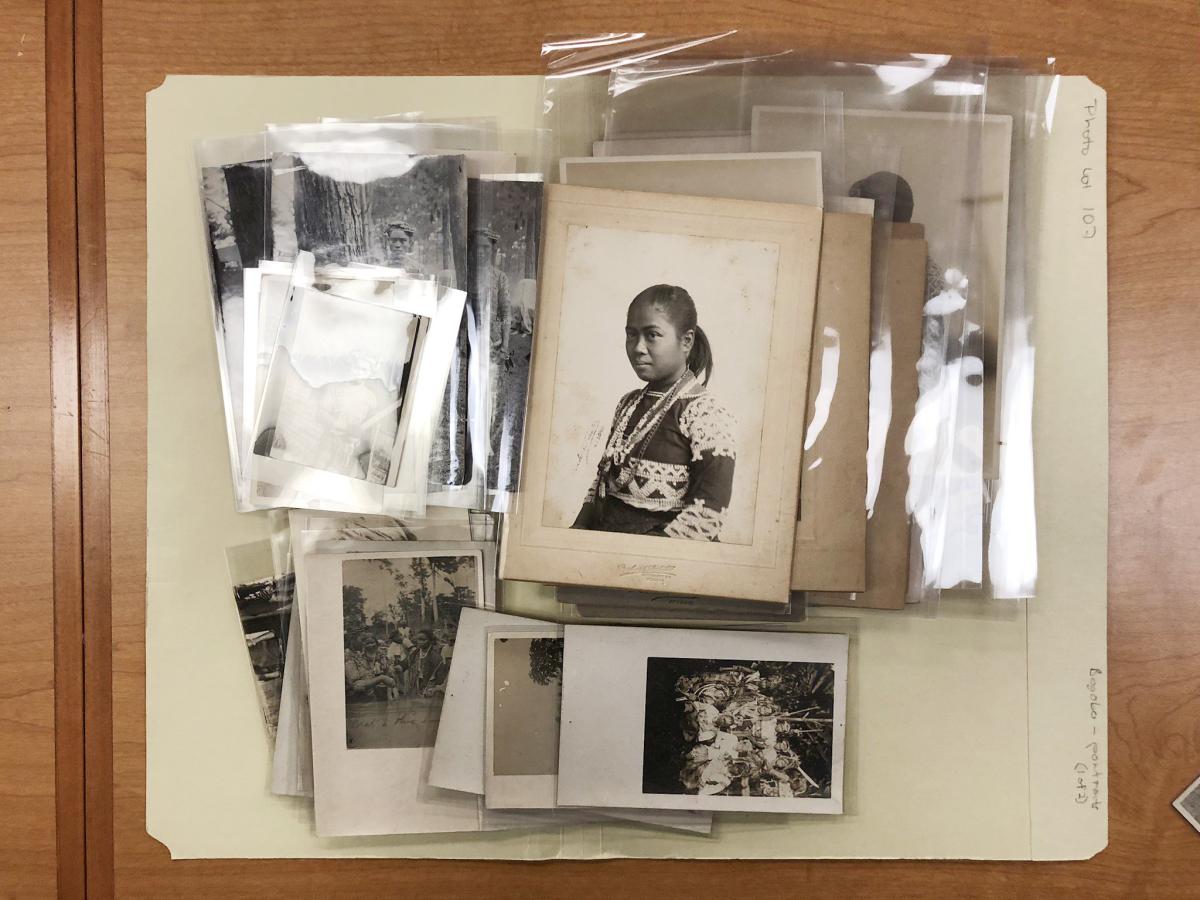

Syjuco’s experience in the archives at the Smithsonian and other institutions inspired a related project, the Rogue Finding Aid, which is currently under development. With this new project, the artist asks the question: What would a speculative, institutionally unfaithful “rogue” finding aid look like, accumulated and conveyed through the critical lens of a cultural informant? “The Rogue Finding Aid is a parasitic image collection that mines and rephotographs institutional archives to center the visual representation of Filipinx Americans for collective research,” said the artist. Above is an example of a rephotographed archive from the Elizabeth H. and Sarah S. Metcalf photograph collection relating to the Philippines, circa 1890-1944, at the Smithsonian National Anthropological Archives (NAA.PhotoLot.107).

Syjuco envisions the Rogue Finding Aid as a parallel, independent database that cuts across many institutional archives and would serve as a resource that prioritized access to Filipinx and Filipinx American researchers, artists, and scholars, many of whom cannot easily travel to the U.S. to view these materials. She explains, “My intent for this Rogue Finding Aid would be to prioritize sharing and viewing of these materials in a responsible manner, and with parties invested in the well-being of the Filipinx community.” Of importance is that the physicality of the archive be present in the finding aid, including the file folders, plastic image sleeves, containers, and even the artist’s own hand. To date, Syjuco has produced her Rogue Finding Aids for the following institutions: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Anthropology Archives, St. Louis Public Library, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis Mercantile Library, and the University of Missouri St. Louis. With any luck this list will continue to grow as other artists and researchers learn of the project and seek to collaborate on this remarkable endeavor to change the way we perceive the past.