The televised trial of Derek Chauvin, the police officer recently convicted of murdering George Floyd, was excruciating to watch. The witness and expert testimony viscerally exposed the inhumanity of Chauvin’s actions and dredged up a long history of similar cases too countless to enumerate. May 25, 2021 will mark the first anniversary of George Floyd’s death and the worldwide demonstrations that ensued, as people in the United States and around the globe wrestled with how this event resonated with the long history of racism and white supremacy.

Last year and still today, I’m reminded of how artists since the 1960s confront themes of police brutality and abuse as a way to express outrage, collective grief, and remembrance. Several works in ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now address police brutality head-on. The exhibition, which explores the rise and ongoing impact of the graphics arts boom among Chicano artists and their collaborators during the civil rights era of the 1960s and 1970s, gathers over one hundred works by many artists who channel their creativity to expose racial oppression. While a major impetus for the Chicano civil rights movement was the labor activism of César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, co-founders of the United Farm Workers union, Chicano activism and politics in the 1960s and 1970s was multidimensional, encompassing anti-war protest, cultural affirmation, educational equality, Third-World solidarity, feminism, LGBTQ+ rights, and, yes, criminal justice. In fact, the works in our exhibition remind us that the struggle against police brutality was part of the civil rights movement from the very start. I’d like to focus on two police brutality-themed works in ¡Printing the Revolution! because they reveal the powerful ways the graphic arts can shine a light on injustice, create a space for communal grieving, and in some cases, facilitate continued activism.

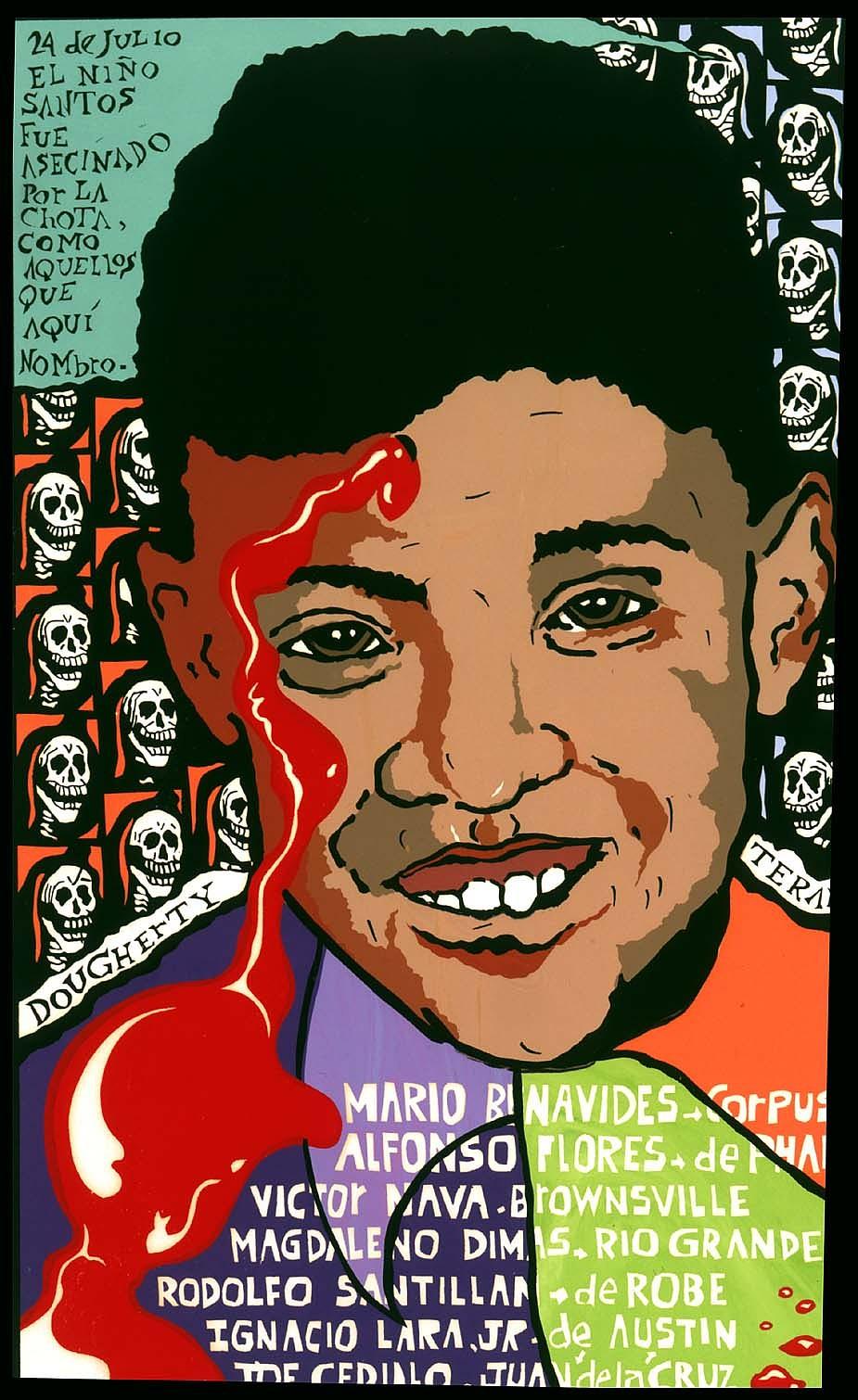

When I learned the story behind Amado Peña’s print Aquellos que han muerto (1975), it shook my soul to the very core. The title of the print, which translates into "Those Who Have Died," immediately foregrounds the theme of death. Santos Rodriguez was a twelve-year-old boy living in Dallas, Texas, in 1973 when he and his brother were accused of allegedly stealing eight dollars from a vending machine. Early one morning, police officers took them in for questioning. While they were seated handcuffed in a police car, one of the officers tried to coerce a confession from Santos by playing Russian roulette. He fired his weapon once and nothing happened. He fired his weapon again and killed the boy instantly. The Mexican American community of Dallas erupted in protest, demanding justice for Santos. Years later, President Jimmy Carter wrote to the boy’s mother expressing his condolences after the Justice Department refused to file civil rights charges against the officer.

Peña, who at the time was an art teacher in Texas, was drawn to the incident because Santos reminded him of his own students. To create his memorial print, Peña may have relied on a school portrait of the young boy. The image, which is both cartoonish and graphic, portrays a smiling Santos with a bloody gunshot wound on his forehead. Peña surrounds his likeness with skulls, a gesture that conjures death and connects with skull imagery frequently used in Mesoamerican and modern Mexican art. The work turns on the juxtaposition of childhood innocence and the depiction of cold-blooded depravity. The colorful print draws you in and then, as the viewer reads the artist’s written message calling out the child’s killing at the hands of la chota (Chicano slang for police), he deals another emotional blow. Like protesters in our own day, Peña frames this act of violence within a longer history of police brutality. In the lower right section of the print, Peña includes the names of other victims of police brutality and the cities where they are from. This gesture, and his use of Spanish over English, conveys the artist’s intent to bring solace and visibility to Chicano communities in the Southwest and to expose a pattern of abuse.

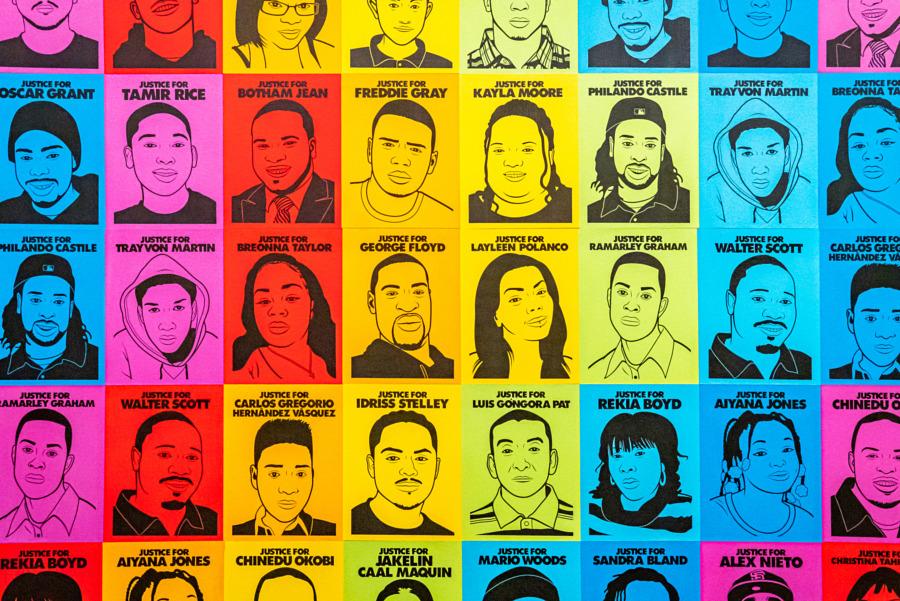

One goal of organizing ¡Printing the Revolution! was to show that the Chicano graphics movement that started in the 1960s continues to thrive today. The act of studying Chicano graphics over five decades brought into greater relief the transhistorical connections revolving around the same struggles, like police brutality. This continuity is why the exhibition juxtaposes Amado Peña’s print with a site-specific installation by Oree Originol. This Bay area artist began his Justice for Our Lives series in 2014 in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement as a way to remember and mourn people killed during altercations with law enforcement. The project started with a portrait of Oscar Grant, the young Black man who was killed in 2009 by a BART police officer in Oakland, California. Since then, Originol has created 100 portraits and completed the series in 2020. To create his likenesses, the artist often reached out to the victims’ families to request a photograph and from these images he creates simple black-and-white digital portraits which he prints and wheat pastes, sometimes in elaborate colorful arrangements, on urban surfaces throughout the Bay Area. His portraits, which portray people full of life, capture the personal style and individuality of his now-deceased “sitters.” He also makes his portraits available for download on his website and encourages users to circulate them on social media and print them for use in protests or in urban interventions. Originol’s project memorializes many Black victims and speaks to the history of Black and Brown solidarity that has long thrived in the Bay Area. His project expands out and documents tragically lost lives in Black, Asian, Latinx, Native, transgender, and migrant communities and for people with disabilities, highlighting how police brutality especially affects politically and economically marginalized groups.

An inherent condition of most graphic arts is multiplicity, which is one reason this mode of artistic expression is strongly tied to political activism. Graphic arts, whether displayed as a print in the home or public space or circulated digitally on social media platforms or the internet, helps visualize and disseminate ideas across communities. Amado Peña’s print, whose image only measures around 15 x 9 inches, is intimate and communicates at personal and emotional levels. Originol’s work is action-oriented; it is a form of protest that facilitates public protest that allows the artist and his followers to respond in real-time to unfolding events. Upon hearing of the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Sean Monterrosa, and Elijah McClain, Originol created new portraits that circulated frequently over the course of 2020 in demonstrations and in public space and on social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok.

¡Printing the Revolution! offers viewers an opportunity to not only acknowledge this long history of violence but to personalize police brutality through the faces of victims staring back at us.

¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics 1965 to Now, which is drawn entirely from SAAM’s leading collection of Latinx art, remains on view through August 8, 2021 before going on tour.