This post is part of an ongoing series here on Eye Level: The Best of Ask Joan of Art. Begun in 1993, Ask Joan of Art is the longest running arts-based electronic reference service in the country. Behind Joan's shield and visor you will find Kathleen Adrian or one of her co-workers from the museum’s Research and Scholar's Center; these experts answer the public's questions about art. Earlier this year Kathleen began posting questions on Twitter and made the answers to these questions available on our Web site.

Question: I’m interested in artwork by William H. Johnson that depicts children as a representation of issues and images from Johnson’s larger African American community.

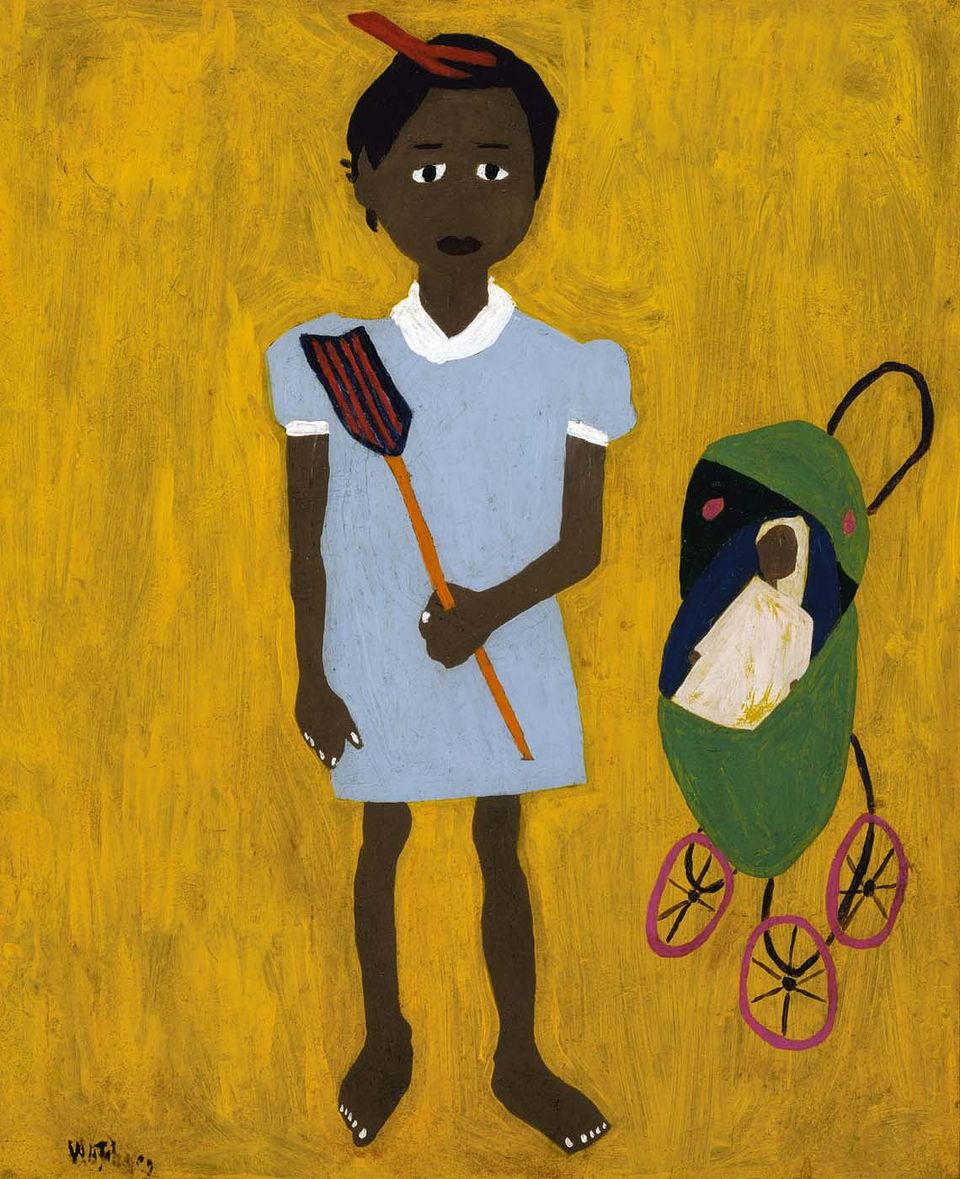

Answer: There are a number of works by William H. Johnson in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum that depict African American children. You can view many of these works on the museum’s Web site.

You may also be interested in the following excerpts from Richard J. Powell’s book Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1991).

Johnson hoped that his family, friends, and the town of Florence [South Carolina] would inspire him, giving his art a little more of the 'peculiar rhythm' and 'directness of feeling' that some of his severest critics felt were wanting in his works. These expectations were alluded to in a letter to Dr. George E. Haynes, written by Johnson after one month in Florence. 'I am feeling around at something.' Johnson told Haynes, 'as I am surrounded by little Negro boys and girls, hoping to abstract something of their [—] and putting it on canvas.' Although it is tempting to guess at what Johnson was suggesting in the empty space that followed his epistolary desire to 'abstract something of' African American youth, the answer perhaps rests in his Florence portraits. Jim, a portrait of Johnson's sixteen-year-old brother, encapsulates much of what was left unsaid in Johnson's half-voiced objective to paint Florence's young, black citizens. A bifurcated background of black and ochre operates as a compositional anchor for the sitter, whose brown, russet and light green colors create a dreamy and lucid effect. The figure's head and shoulders are not so much depictions of flesh and fabric as they are painted gestures of both the sitter's and Johnson's shared moods of anticipation and anxiety. [pp.44–46]

Study for Playground Scene, a drawing originally intended as a mural story for the Federal Art Project, reveals another side of Johnson's homage to Harlem and urbanity: children's culture in the inner city. Johnson's outlined and geometric treatment of the children and their urban environment transforms this drawing into an animated scene of shifting circles, parallel bands and other linear configurations. Though incomplete, Playground Scene and other works by Johnson that examine urban child's play convey an almost conceptual sense of city children and their activities.

Although Johnson had long been an avid supporter of encouraging children in the visual arts, his tenure at the Harlem Community Art Center formalized this advocacy, as it regularly exposed him to the direct, colorful statements of those budding artists. Child artists, like the one shown kneeling and drawing in the lower left corner of Playground Scene, fueled Johnson's imagination and inspired him to continue pursuing a two-dimensional, non-illusionistic approach to painting. [pp.132–135]

The circa 1942–43 gouache, Lift Up Thy Voice and Sing is a strange mixture of African-American folklore and political commentary. The scene, showing eight black children singing under the direction of a chorale leader, with all of them standing in front of an inverted American flag, posed innumerable questions.... The answers to these questions can be found in Johnson's evolving attitudes toward the contrasts between the conditions of African-American life and those of the rest of society.... Johnson's use of the navy's distress sign was double-edged: it is a comment both on the desperate battlefront situation and on the signs of distress and dissatisfaction among blacks on the domestic front. That Johnson's black youth in this painting raise their voices and sing in the face of a crisis is, however, not so much absurd or satirical as a sign of hope, an affirmation of the human spirit. [p.178]

A great deal of information has been published about William H. Johnson and his works. You might be interested in taking a look at these sources: Free Within Ourselves: African American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art by Regenia A. Perry, William H. Johnson by Adelyn Dohme Breeskin, and William H. Johnson: Truth Be Told by Steve Turner and Victoria Dailey. In addition, Gwen Everett has written a children's book based on Johnson's painting and his other works: Li'L Sis and Uncle Willie, which is available from our online shop.

To get in-depth information on this subject or to ask your own art questions, please visit Ask Joan of Art!