Sophie Rivera's untitled photographic portraits

Curator E. Carmen Ramos and curatorial assistant Florencia Bazzano-Nelson discuss Sophie Rivera's untitled photographic portraits that will be included in our upcoming exhibition Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art, opening October 25, 2013. Like other artists in the exhibition, Rivera created monumental images of everyday people. More than straightforward portraits, these works reflect on the act of representing traditionally ignored and stereotyped people and cultures. This is the latest post in an occasional series highlighting some of the exciting artworks that will be featured in Our America.

Depictions of Nuyoricans—or Puerto Ricans from New York—in American popular culture have long been sites of tense encounters. Puerto Ricans became one of the most recognizable Latino groups in New York City ever since the 1950s when migration from the island to the continental United States exploded. Puerto Ricans enriched the city's cultural life in numerous ways. They actively participated in the Mambo and Salsa booms in the 1950s and 1970s, and they founded important cultural institutions like the Nuyorican Poets Café and El Museo del Barrio. Despite these enduring contributions, the prevailing image of Puerto Ricans in the media has been stereotypical. Films such as West Side Story (1961) and Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981) portrayed Puerto Ricans as criminals and gang members. Community protests against Fort Apache, the Bronx were especially intense, as activists from the South Bronx region of New York cried out against the image of Puerto Ricans and African Americans as instigators of social decay.

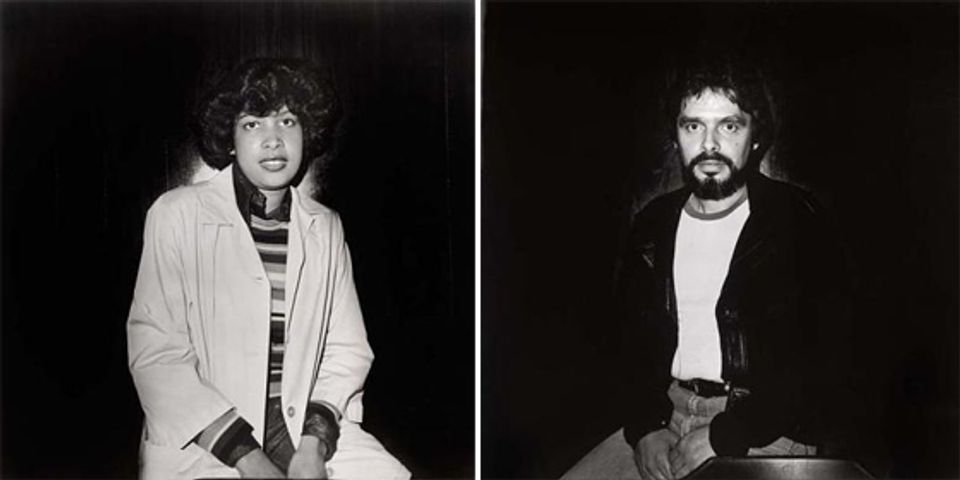

It was during this period of struggle that Sophie Rivera decided to document New York City's Puerto Rican community through photography. Her two untitled photographic portraits in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum feature Puerto Ricans who traversed the city. Rivera sought out her subjects in an unusual way. Standing outside of her building, she asked passersby if they were Puerto Rican. If they answered yes, she invited them to her studio and photographed them against a wood-paneled background. She produced at least 50 black and white portraits, although only 14 survived a fire in her studio.

What is striking about these portraits is how they capture the tension between the artist's desire to represent her community and the open ended nature of the images themselves. Both the man and the woman featured in these photographs respond with a steady, confident gaze to the glare of the intense limelight that shines on them, which recalls the harsh light used during interrogations or in crime scenes. The size of the photographs—each is four feet square—monumentalize the subjects and magnify details. The sitters present themselves in a relaxed, dignified, unsentimental way, with their hands demurely folded in their laps. They are fashionably dressed and their hair styles are trendy. The man's eyes are sunken and he looks slightly weathered. He wears a beaded necklace suggesting that he may be a practitioner of Santeria, an Afro-Caribbean faith. The young woman's hair is styled after Farrah Fawett's famed feathered and flipped hairdo. She also wears a light-colored smock and perhaps works at a local hair salon or supermarket.

Rivera's portraits challenge stereotypes of Nuyoricans not by offering a positive representation of Puerto Rican life in New York but by letting the individuality of everyday people speak for themselves. Unlike traditional portraits, which often identify sitters by name, Rivera's subjects remain anonymous, even to her. By visually revealing her subjects in great detail and directness, yet leaving them un-named, Rivera allows viewers to reach their own conclusions about who these individuals are and what they represent.

The exhibition Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art will run from October 25, 2013 – March 2, 2014.