Eye Level, with the help of former intern Becky Harlan, had a chance to speak with photographer Muriel Hasbun about her artistic roots and her current process. Her work appears in the current exhibition, A Democracy of Images: Photographs from the Smithsonian American Art Museum as well as Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art, which opened at the museum on October 25. Hasbun is the chair of Photography at the Corcoran College of Art + Design in Washington, D.C.

Eye Level: What triggered your interest in art and photography and how has your approach to art changed since you first began working?

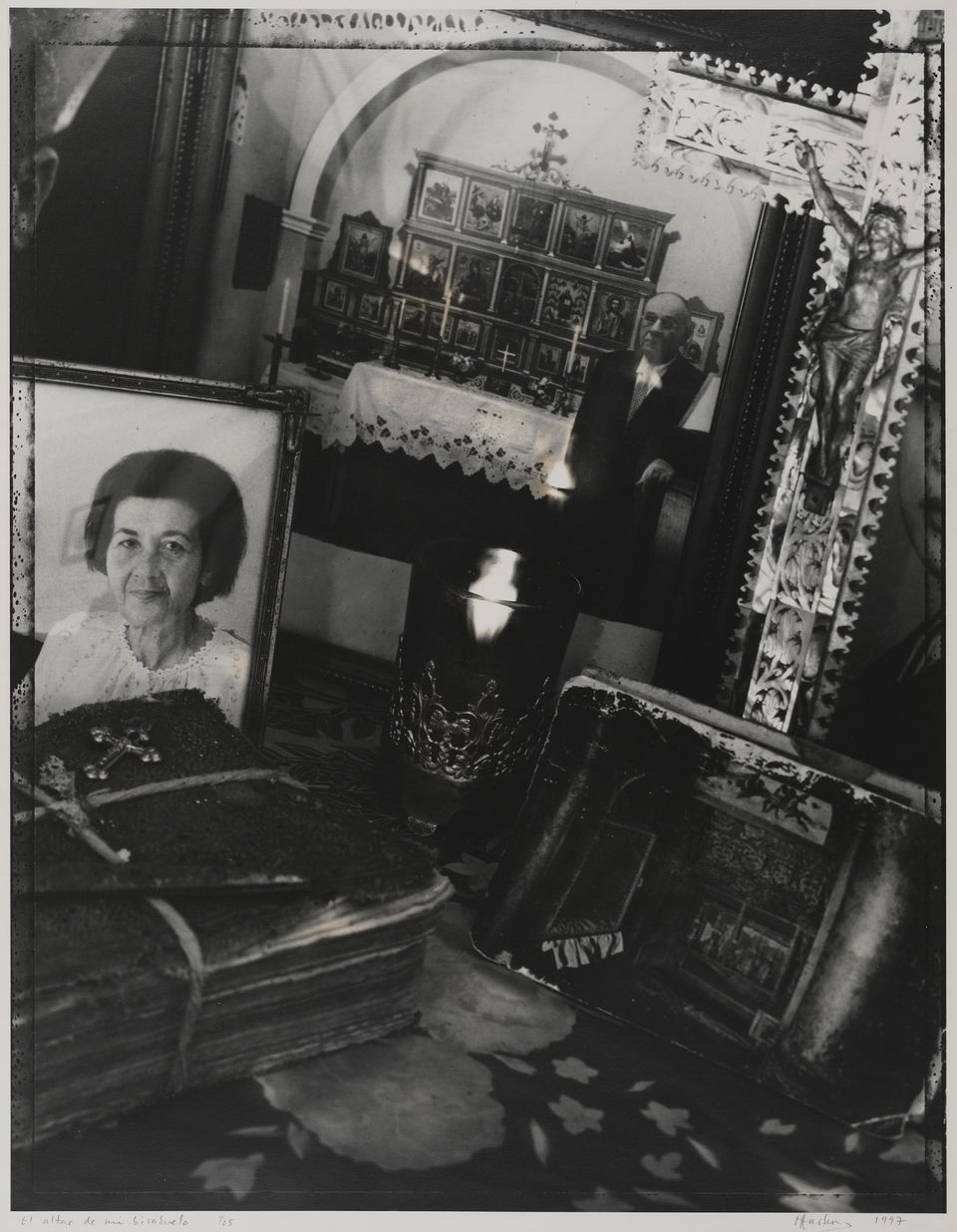

Muriel Hasbun: I owe my first arts education to my parents. My mother, Janine Janowski, owned an art gallery in El Salvador, and my father, Antonio Hasbun Z., was an accomplished amateur photographer. As a shy 16 year old, I began to take pictures of my friends with a 35mm camera that my father gave me. After my literature undergraduate studies, I returned to El Salvador and documented children displaced by the civil war. Once back in the U.S., I focused my energy on unraveling and constructing my own sense of identity. Santos y sombras/Saints and Shadows, of which there are two images in Our America, is the first iteration of that search. Other series, like Auvergne-Toi et Moi and Protegida/Watched Over continue to investigate the relationship between personal memory, post memory, and collective history. Through teaching, and since 2006, when I was awarded a Fulbright Scholar grant to El Salvador, my efforts have also involved creating sites of cultural exchange.

EL: You have said that you work through an "intergenerational, transnational, and transcultural, lens." Can you elaborate on that?

MH: Throughout my career, I have employed photography to investigate issues of identity, memory and inter-subjectivity. My own Palestinian/Salvadoran Christian and Polish/French Jewish family is multivalent, multilingual and multicultural. I’m the product of multiple exiles and diasporas, including my own. By necessity, I traverse boundaries, and I’m drawn toward creating a template for understanding.

Through my work, then, I explore a territory where negotiating allegiances to multiple cultures, religions, and languages is the norm, rather than the exception. I do this by stitching together fragments of the past into elusive narratives in the present, in a dialogue between personal and collective history.

EL: Your work is based out of your family's history, how do you hope that translates to the individual viewer?

MH: The initial investigation of my own family history was a strategy to reconcile the irreconcilable. I began gathering and closely scrutinizing family photographs and documents that had been previously dispersed and unexamined. Little by little, I realized the power of learning the stories and historical events surrounding the archive. This became a method of inquiry and part of my creative process. It also became a way of engaging my own family and the greater community in a dialogue about our individual and collective sense of identity.

I have always been interested in photography as a means of translating or evoking aspects of our subjective reality. The multiple layers in my photos, as well as sound, video and other installation elements help immerse the viewer further into the emotional aura of the work. Many of my projects like barquitos de papel/paper boats and Documented: The Community Blackboard have a relational or public intervention component too. In the video installation, barquitos de papel the public is asked to add paper boats inscribed with personal stories of migration, and Documented invites the public to contribute family photos and writing onto the exhibition walls. In my recent show at the Corcoran’s Gallery 31, I asked members of the public to write or draw their own stories of trauma occasioned by war onto one of my photos of X post facto. Through these different strategies of engagement, I’m assembling a collective archive that sheds light on the interconnections and shared experiences that exist between us, regardless of which nation’s passport we might happen to carry.

EL: Whose work are you most inspired by?

MH:The French Surrealist poets, Marcel Proust, Jorge Luis Borges and T.S. Eliot first provided a framework for my desire to employ photography as a poetic or narrative medium. Man Ray and Lotte Jacobi were a great influence, as was my mentor Ray Metzker, who encouraged me to play and strive for inventive experimentation. My colleagues and students at the Corcoran inspire me every day.

EL: What is your biggest challenge as an artist?

MH: The biggest challenge is balancing time and resources for creating one’s work.