Martín Espada's incantatory poetry reading at SAAM in honor of Down These Mean Streets: Community and Place in Urban Photography paid lasting tribute to his father, the documentary photographer Frank Espada (1930-2014), whose work is featured in the exhibition. The elder Espada was also a community organizer, civil rights activist, and a leader of the Puerto Rican community in New York in the 1960s and early 1970s. Martín Espada's reading captured formative moments in his father's life that would become enigmatic in his own. In addition to being a renowned poet, Martín Espada is an essayist and attorney who has dedicated much of his career to the pursuit of social justice and Latino rights. De tal talo tal astilla—Like father, like son.

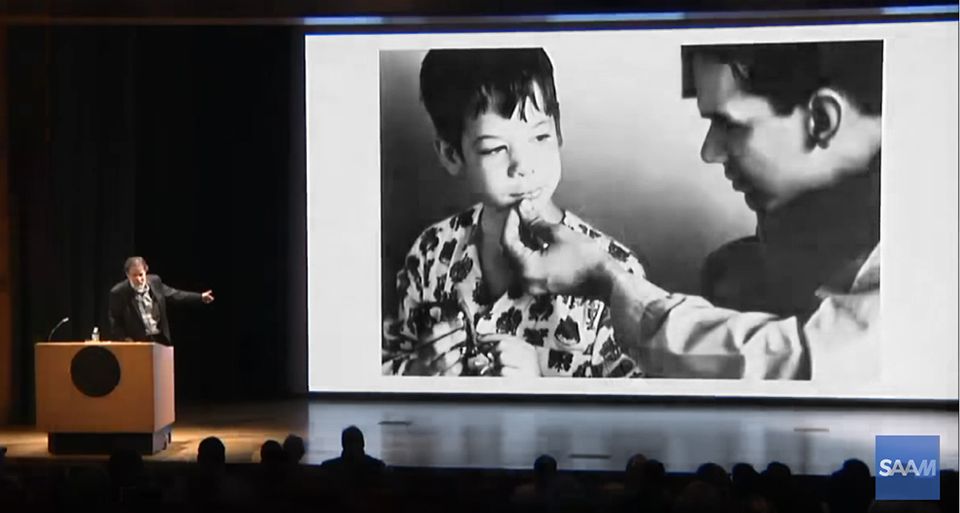

"I am, especially tonight, very proudly my father's son," Martín announced, then projected a photograph of the two of them, taken by his mother when he was seven years old. It was about this time, he told us, that he became aware of his father as an activist, someone who might unexpectedly disappear for a few days at a time. During these absences, Martín was sure his father was dead—he would soon learn that "sometimes Puerto Ricans die in jail"—until he walked through the door a few days later. "That day, my father returned from the netherworld," Martin recited, "...I searched my father's hands for a sign of the miracle." The theme of disappearance and reappearance was a thread that made its way throughout the reading. When he was nine, Martín started attending protests, marches, and candlelight vigils with his father, including one for a man named Agripino Bonillo, a Puerto Rican kitchen worker and father of nine who was murdered in East New York, Brooklyn. "This was part and parcel of my education...It's not something you forget. And I didn't," he told us, before reading the poem he wrote about the events titled "The Moon Shatters Over Alabama Avenue."

In the summer of 1981, Martín was twenty-three and working with his father who was documenting burned-out buildings in Manhattan Valley, a thirty-square block area on the West Side of New York City, where arson for profit was rampant. In Frank Espada's portrait of José Acuña, director of the Manhattan Valley Development Corporation, a tenant advocacy group, you see him in a fire-gutted apartment, his white shirt in sharp contrast to the soot black of the setting. Martín told us that he was there, just outside the frame, carrying the camera bags and tape recorder. Moved by the situation, he wrote a poem soon after, about one of the tenants who couldn't afford to leave the desolate building, "Mrs. Báez Serves Coffee on the Third Floor." The poem concludes: Someone poured gasoline/ on the steps outside her door,/ but Mrs. Báez/ still serves coffee/ in porcelain cups/ to strangers,/ coffee the color/ of a young girl's skin/ in Santo Domingo."

The theme of fathers and sons continued through the generations with the birth of Martín's son, Klemente (now twenty-five). The poem he read, "Of the Threads That Connect the Stars," celebrates the three Espada men, their different ways of seeing and interacting with the world, and "the changes that happen without our even realizing it." For Frank, seeing stars had the rough-and-tumble meaning of getting walloped in the face until you saw stars or flashes of light. Martín recalled his childhood and writes, "I never saw stars. The sky in Brooklyn was a tide of smoke rolling over us from the factory over the avenue..." Klemente, however, can look through a telescope at the infinite universe and "name the galaxies." One generation makes way for the next...

Martín concluded the evening with an elegy. He wrote "El Morir Vivir," for his father's memorial service three years ago. "I found the metaphor to capture the many lives, births, and deaths of Frank Espada," he told us. El morir vivir is a pan-tropical weed whose name literally means, "I died, I lived." If you touch the leaves they curl up; after a while, they will uncurl. I died, I lived. Absence and presence. A man dedicated to his causes, his friends and his family, Frank Espada lives on not only in his family, but in his son's poetry and his own passionate photographs.

If you were unable to attend the poetry reading, you can watch the webcast here.

In addition, watch Martín Espada and Jeffrey Brown, chief correspondent for arts, culture, and society at the PBS NewsHour, in conversation at SAAM, discussing Frank Espada's life and work.

Bring your family to SAAM this Father's Day to see selections from our extensive collection of Latino art in the exhibition Down These Mean Streets: Community and Place in Urban Photography. It's on view through August 6, 2017.