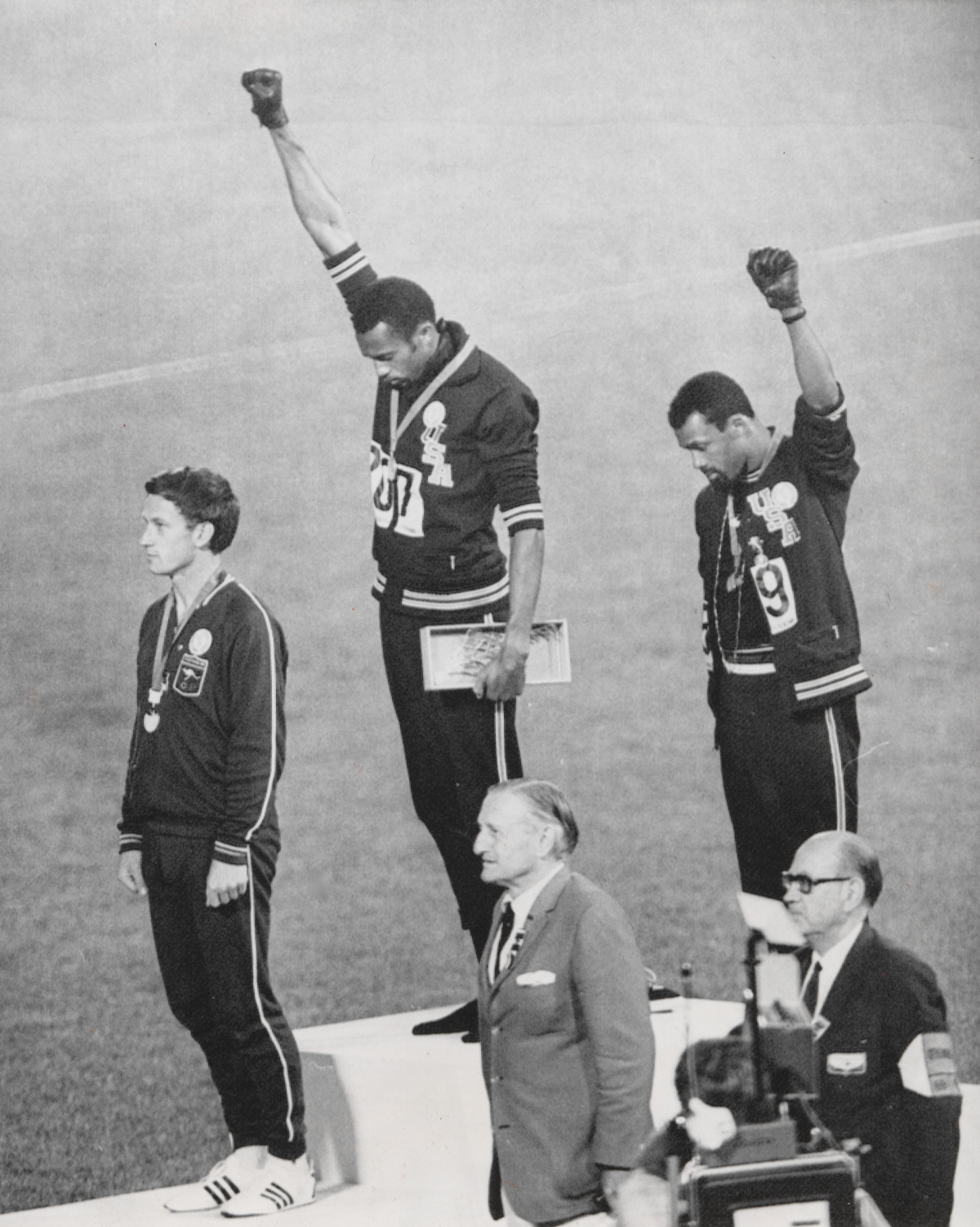

On October 16, 1968, during the medal ceremony for the men’s 200-meter race at the Mexico City Olympic Games, Tommie Smith, the American winner of the event, raised his black-gloved fist as a call for unity and an act of protest for human rights. Echoed by the bronze medalist John Carlos, the gesture was seen around the world. Smith’s raised fist became the inspiration and catalyst for a multitude of social causes, and more personally, irrevocably changed the course of his own life.

In 2013, Glenn Kaino created Bridge, a large-scale sculpture, as part of an ongoing collaboration with Smith. It serves as a memorial to one person’s action and the legacy of that action through time. The work comprises 200 gold-painted life casts of Smith’s outstretched arm, suspended from the ceiling in a sinuous line. Nearly 100 feet long, it reaches both backward and forward. It evokes the power of gestures and ideas through history, as a bridge through time and space into the present.

SAAM is in the process of acquiring Bridge and plans to present the work in 2023. What follows is an interview between Sarah Newman, the James Dicke Curator of Contemporary Art, and its creators.

Sarah Newman: I saw Bridge in DC in 2014, the first time you exhibited it. At that point it seemed like it was asking us to acknowledge the enormity of Tommie Smith's gesture and to argue for its place in history. Now, only seven years later, the ramifications of his action are apparent and his status seems unquestionable. How has it felt to witness that change through this work?

Glenn Kaino: That first exhibition was certainly intended to declare a connection from the past to the present. It was a bridge from generation to generation and a call to acknowledge how we are all our past and our future. It was also our first major exhibition of the full sculpture—until then, we had only been able to afford to make smaller segments. When our full vision was realized, it opened up the doors to thinking about our other long-term goals.

Many of our ambitions from 2014 have been realized throughout this amazing journey, including having the artwork live in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It’s the timeless nature of Tommie's intention that resonates so strongly today and that will inspire generations to come.

How did you come to know Tommie Smith, and what is it like to collaborate with him?

I had a small picture of Tommie and the famous salute taped to the corner of one of my computers in my Los Angeles studio. One day a friend came to visit and he pointed at it and said, “Coach Smith! Want to meet him?” To be honest, at that moment, I didn't know if Tommie was even alive, let alone the depth of his story. But I immediately said yes and booked two tickets to visit him at his home in Atlanta.

When I arrived, Tommie generously greeted me at the door. He shook my hand, sat me on his couch, and played the race he won in slow motion, narrating each step. When he was done, I was speechless. I explained to him that I wasn't there to suggest any artwork but to ask if he would be interested in collaborating on a long-term project to help bring his story to the world in a new way, allowing him to be a witness to the rich history he has inspired. We then met in Los Angeles shortly after and I cast his arm as a first experiment, and, from that, came Bridge.

It has been the honor of a lifetime to be trusted to collaborate with Tommie and help create works that bring a fuller range of his story to the world.

In recent years, your work has centered on activism and protest. What caused your thoughts to focus so clearly on this topic?

I have always been a student of revolution, changemaking, and the successes and failures of movements— long drawn to stories of sacrifice and dedication. From when I was very young, I felt the need to speak out against injustice. Becoming an artist allowed me to utilize creative and critical thinking together in ways that allowed for some of my ideas to be brought to the public.

Artists get to imagine for a living, and imagination is a perishable skill. We have to use it to continue to know how to use it. I think one of the most important roles of an artist is to imagine new futures, to think about what we can become as a society and to use their work to inspire change.

You are about to release a series of NFTs on the subject of Tommie Smith and around the theme of civil rights. What drew you to this new medium and what excites you about it?

I have been working in digital space for quite some time, so it was natural to consider a new way to carry Tommie’s message forward in that realm. Back in the 1990s I was part of an early group of digital pioneers and did everything from launch the first website for artists of color to helping make the first legal music streaming service as the Chief Creative Officer of Napster 2.0, to my work today with Jesse Williams now and our company VISIBILITY.

The NFT project with Tommie will be a way for us to channel the strength of Tommie’s story, and particularly the story of his famous relay races, into a direct support channel for social justice activists, leaders, and organizations from the past and the present. It's exciting because this project is only possible with blockchain technology, and we feel we are using new tools to create space and real change for communities of color within technology. We hope it inspires others to take the baton and run with it.

What makes SAAM an appropriate place for Bridge?

My work in collaboration with Tommie is about his legacy, and how we can secure it now and for future generations. We call ourselves his “Legacy Team.” Having Bridge at SAAM is a wonderful and special achievement and we are incredibly grateful to know that the story of our work, and Tommie's generous intention of utilizing his sacrifice for all human rights, will be part of the rich history of art in this country.

Tommie, what you were thinking and experiencing on that day in 1968, and how does Bridge express that?

Tommie Smith: That day was a long time coming. I wanted to make sure that the truth got out, my truth, from the heart. And my truth was standing up for all human rights. I was a part of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, and I knew going into the event that something needed to be done. Raising my arm meant pride, it meant togetherness—all of us—as a nation.

Part of my body is in Bridge, and I will forever be part of the movement that my salute and that the work inspires. It's why we are creating the Legacy Team, to continue to teach people about human rights and how we are all connected.

How has your understanding of your action changed over the course of a half century?

Back then, right after the Olympic Games, people didn't believe that it was the right type of radical act. Changes are happening in society now, and it is evolving too. It was a physical gesture only before. It was symbolic but silent, and now it's an artwork and film. Now it's verbal.

Once I started teaching and speaking, I began working on my voice the way I worked on the track. But we haven't gotten to the finish; I'm in a longer race now.

What has been the process been like collaborating with Glenn? How do ideas emerge and get hashed out?

Glenn is a person who listens and understands what I was doing. I needed someone like him to help make the salute a new story, and now we are giving a voice to that silent gesture and inspiring people with these new works.

I am a door; I just needed someone to open it.

What are your thoughts about the work becoming part of SAAM’s collection?

It was a dream of mine to be in the Smithsonian but also, for me, it was an inevitability of my thought process. Once I met Lonnie Bunch [who was at the time the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture] and learned about his work there. Now, as the leader of the larger Smithsonian, I knew that SAAM was the place for the Bridge.

How close to heaven can you get besides stepping in the front door?

I have to thank God for his acceptance, and we thank everyone at the Smithsonian for inviting us to be part of the museum and part of the story of American art.