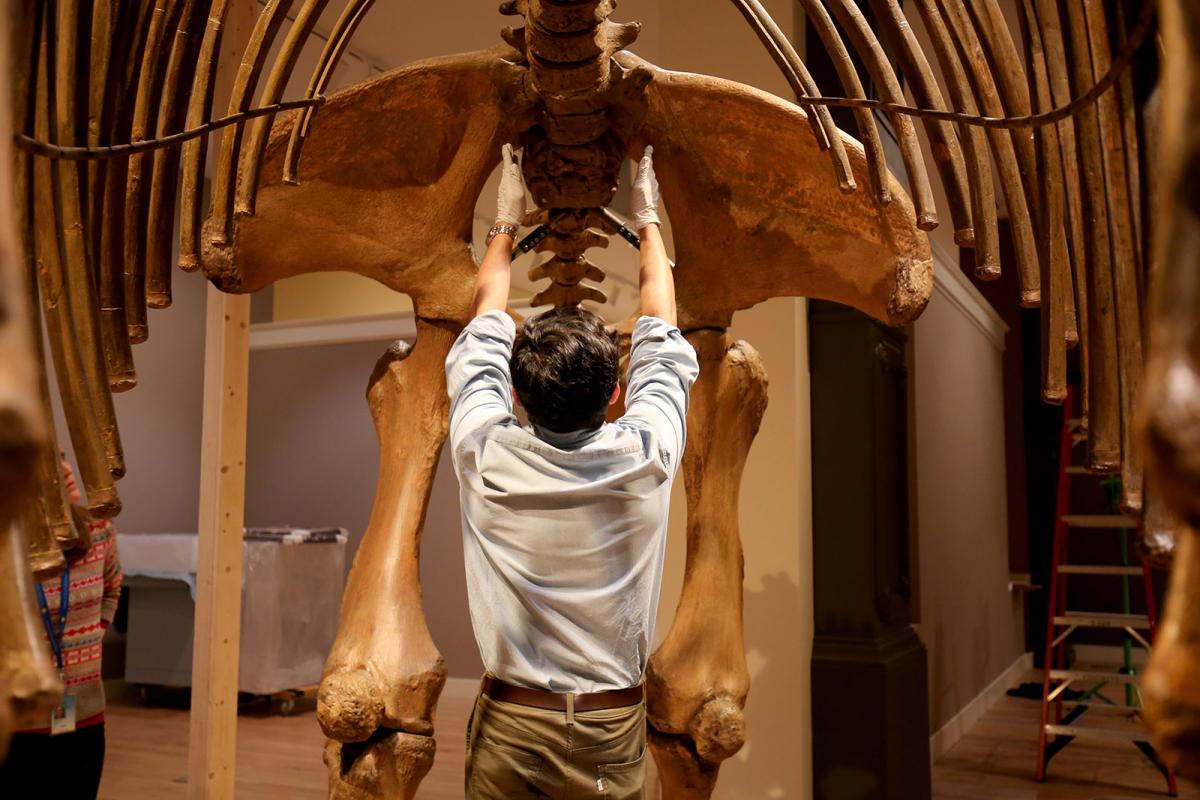

While the Smithsonian American Art Museum rarely houses fossil remains, an amazing specimen, the original “Peale Mastodon” skeleton, is part of the upcoming exhibition Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture. It's inclusion in the exhibition represents a homecoming for this important fossil that has been in Europe since 1847, and emphasizes that natural history and natural monuments bond Humboldt with the United States. Eye Level talked with a paleontologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History to find our more about mastodons.

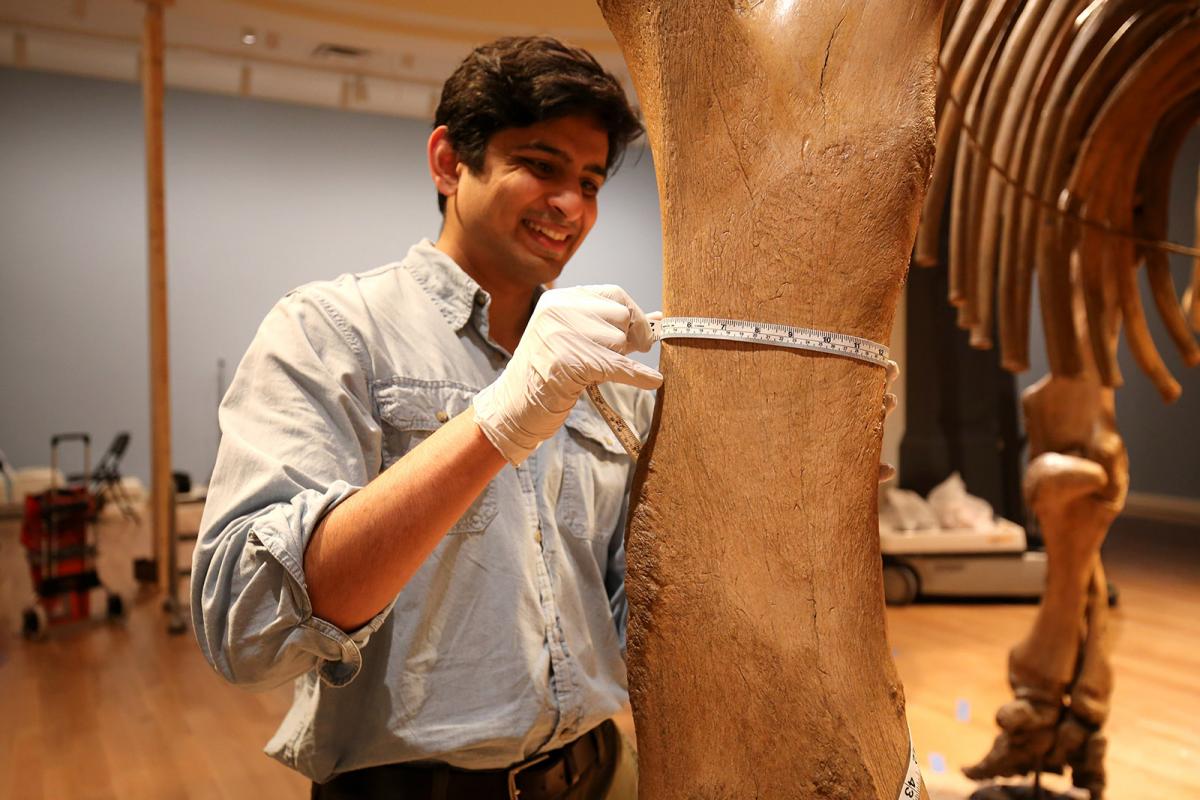

The American what? The American Incognitum. No, I’m not talking about an X-Men character here, I’m talking about a distant relative of the modern-day elephant. The name, American Incognitum, traces back to the first discovery of mastodons in the world. Back in 1705, a Dutch farmer in upstate New York dug up a tooth and no one knew what it belonged to. The animal’s identity was concealed hence the nickname “incognitum” from the root word “incognito.” The farmer ended up selling the tooth to a local politician for a pint of rum and the name was formed. But who really was the American Incognitum? To answer these questions, I talked with Deep Time Fellow and Paleontologist Advait Mahesh Jukar at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.

Before we get into the details, let’s review our timeline here. Did dinosaurs, woolly mammoths, mastodons, and elephants all live together? Advait explains that non-avian dinosaurs—technically birds are “dinosaurs”—went extinct 66 million years ago. This species of mastodon shows up about two million years ago and went extinct roughly 12,000 years ago, so it likely did cross paths with woolly mammoths and elephants. Elephants are the only living mammal from the group that still exists today. However, don't forget that elephants are not descendants, but share a common ancestor with mastodons.

Let’s talk about those tusks. Just like modern-day elephants, mastodons also had tusks. Advait said they more than likely used them to show off, push over vegetation, and possibly to fight off predators. Their tusks were made of dentin, just like our teeth, but without the enamel coating. The mastodon skeleton installed in the Humboldt exhibition has reconstructed tusks, which have actually been created three different times in its fossil lifetime. Because the tusks were missing when the skeleton was unearthed, the artist Charles Willson Peale first constructed them out of paper mâché. These tusks were destroyed during World War II. When they were reconstructed a second time, the shape of the tusks had more of a tight circular curve. For this exhibition, they were reconstructed once more to be more realistic changing the curve to be more relaxed and extend outward more.

We know that this species of mastodon existed about two million years ago, but how long was this mastodon’s life span? To be honest, we don’t know says Advait. But, from the skeleton and tooth wear, we can assume it lived until to be about 50 years old. The modern-day elephant lives between 50–70 years of age in the wild. Assuming mastodons are similar enough to elephants, we’d say this mastodon had a pretty long life.

More importantly, what or who did this mastodon eat? Advait assures me, mastodons were vegetarians. They were known browsers in their food choices, so leaves and twigs would have made a delicious meal. A mastodon probably weighed about six tons, similar to a modern day African elephant. To maintain this weight, a mastodon would have had to eat about 200 to 400 pounds of salad every day, so constantly browsing is a more appropriate way to describe it.

Some big questions still remain. Who was this mastodon? How did it die? Did it live in a herd or some other family structure? We will never be able to fill all the gaps in this mammal’s timeline, but we can make one educated guess. For instance, based on the structure of the hips, Advait tells me this mastodon was likely male.

To learn more about Humboldt, his influence on art and culture in the United States, and mastodons, watch SAAM Senior Curator Eleanor Harvey’s tour of the exhibition Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture, which has not yet opened to the public as part of the Smithsonian’s efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19. Our sister museum, the National Museum of Natural History is a great place for further discovery of mastodons, elephants, woolly mammoths, and yes, even beloved dinosaurs.