In 2023, SAAM acquired exemplary paintings by two groundbreaking figures of American art: Hisako Hibi and Matsusaburo Hibi.

Both were part of the vibrant and diverse art scene that thrived in San Francisco between the World Wars. Immigrants from Japan, they met in San Francisco in the late 1920s, when Hisako (née Shimizu) was studying oil painting at the California School of Fine Arts. Matsusaburo was already an established figure, having played a central role in organizing the East West Art Society, an association that brought together artists and art traditions from Europe and Asia. The couple married in 1930 and later moved to Hayward, California, where Matsusaburo opened a school for Japanese language and art. Even as they had two children, both continued to exhibit regularly, Hisako becoming one of only three Japanese American women to have work included in the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-40.

However, little of the art Hisako and Matsusaburo Hibi created before World War II survives today. As with scores of other Japanese Americans, the events of the war sharply impacted the Hibis’ lives. In one of the worst civil rights violations in the history of the United States, the issuing of Executive Order 9066 in 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, mandated the mass removal and incarceration of people of Japanese descent from the West Coast. Given about a week to prepare and told to bring only what they could carry, the Hibis had no choice but to leave their paintings behind. The Hibi family would spend more than three years in government detention, mostly at the Topaz Relocation Camp in the high desert of Utah. When the war ended, they moved to New York City. Matsusaburo died of cancer less than two years later, in 1947. By the time Hisako returned to California in 1954, their earlier artwork could not be found.

The Hibis’ story underscores the vulnerability of historic Asian American art. Although the Japanese were the first group of Asian immigrants to significantly participate in American modernism, their contributions have been largely invisible in scholarly and public conceptions of U.S. art and culture. Family members, a few committed collectors and art historians, and institutions dedicated to preserving Japanese American history and culture have been most responsible for protecting their work and bringing it to public attention. It remains now for large art museums such as SAAM to contribute to the recuperation and reintroduction of artists like Hisako and Matsusaburo Hibi to the history of American art—through acquisitions, exhibitions, and new scholarship.

Thanks to a crucial introduction provided by the scholar ShiPu Wang, I had the opportunity to meet Ibuki Hibi Lee, the daughter of Hisako and Matsusaburo Hibi, in 2022. In an apartment in San Francisco, I was astonished to see the number and variety of artworks cared for by Ibuki and her family members for decades. Four paintings, now in SAAM’s collection, stood out immediately, two of which were created while the Hibis were incarcerated at Topaz.

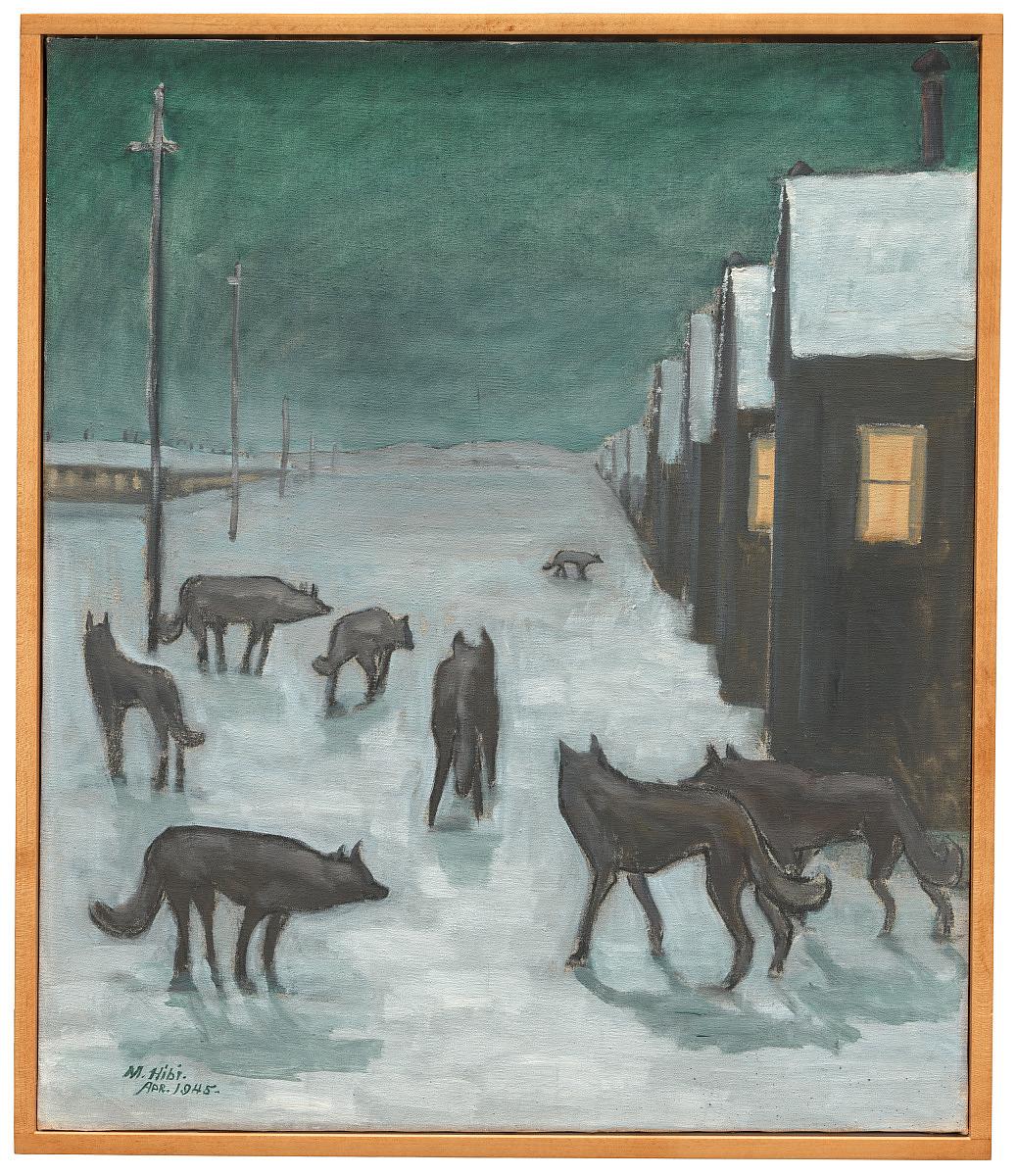

Matsusaburo’s Coyotes Came Out of the Desert (1945) depicts a group of animals roaming the camp barracks, seemingly in search of prey. The painting may relate to an actual event—the artist inscribed on its back: “It was a hard winter in Topaz the snow [lay] deep. Big [coyotes] came out of the desert right up to the camps and no one dared to go out of the doors.” But the work also masterfully conveys an atmosphere of dread and unease, emotions surely felt by the inmates as they lived under surveillance and grappled with the loss of their freedoms.

Hisako’s Floating Clouds (1944) is similarly both specific and universalized, grounded in observed reality yet transcendent in theme. While many of her camp paintings feature small figures in the landscape, here she omits the ground entirely, directing our gaze past the geometric rooftops of the barracks to the luminous clouds above. Hisako later inscribed on the back of the canvas: “‘Free, free’….I want to be free/ Free as that cloud I see up above Topaz.” Trapped in an oppressive environment and surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers, it is no wonder she turned to the sky for solace and mental escape. In its boundlessness, the sky suggests freedom as well as connection—it is shared by everyone on earth. The sky Hisako gazed at from Topaz was the same sky all Americans looked up to from across the vast United States.

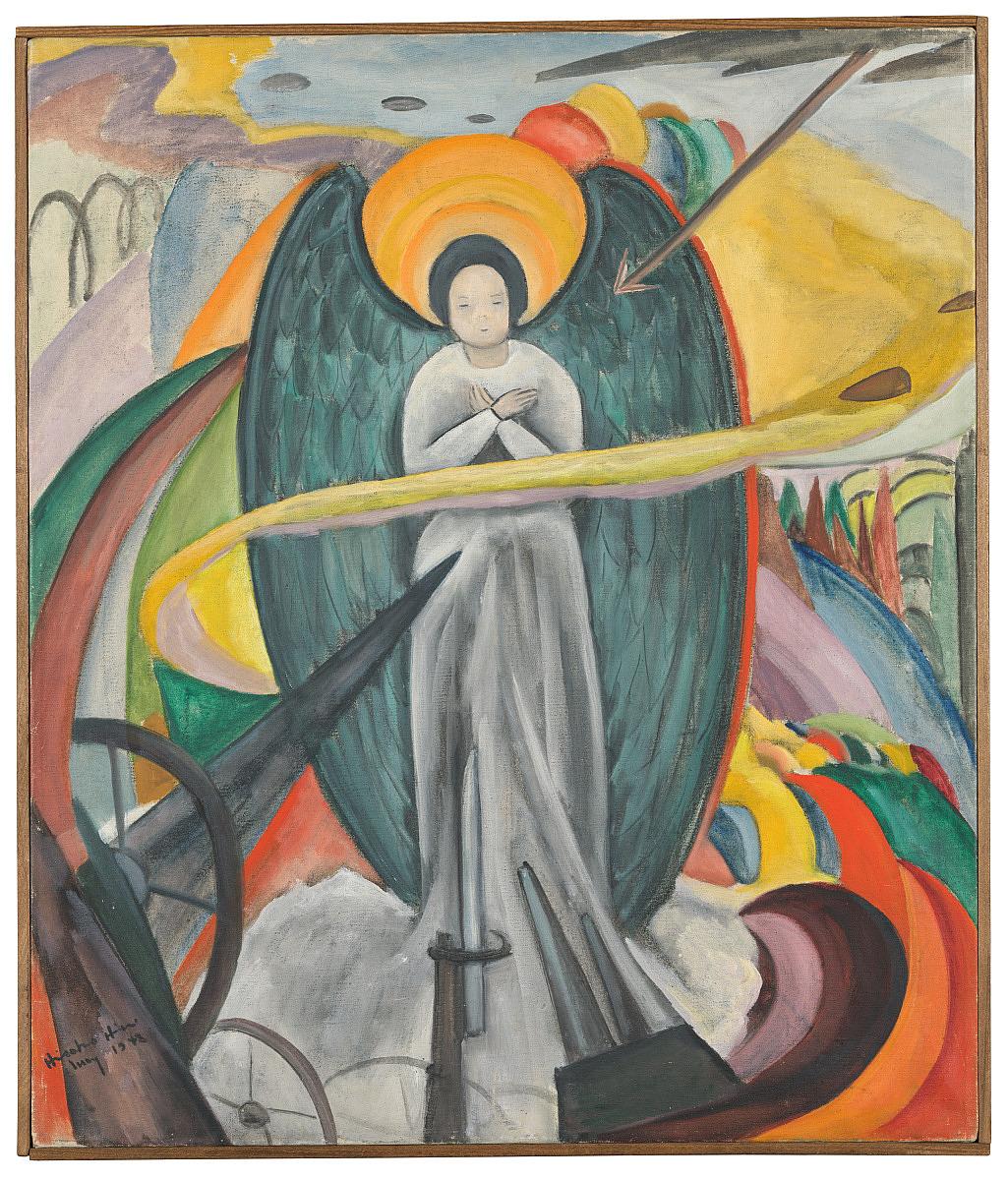

After the death of her husband, Hisako supported her family working as a seamstress in a garment factory. Despite financial hardship, she continued to paint and grow as an artist, her work becoming more colorful and driven by her imagination. Some of her New York paintings reflect the artist’s anxiety and isolation at the time, depicting the city as a frightening, nightmarish landscape. Others, such as Peace (1948) are more hopeful statements. The painting shows a beatific angel facing down weapons of war, subject matter that reflects Hibi’s deeply held pacificism and ongoing engagement with art as a means of personal and spiritual consolation.

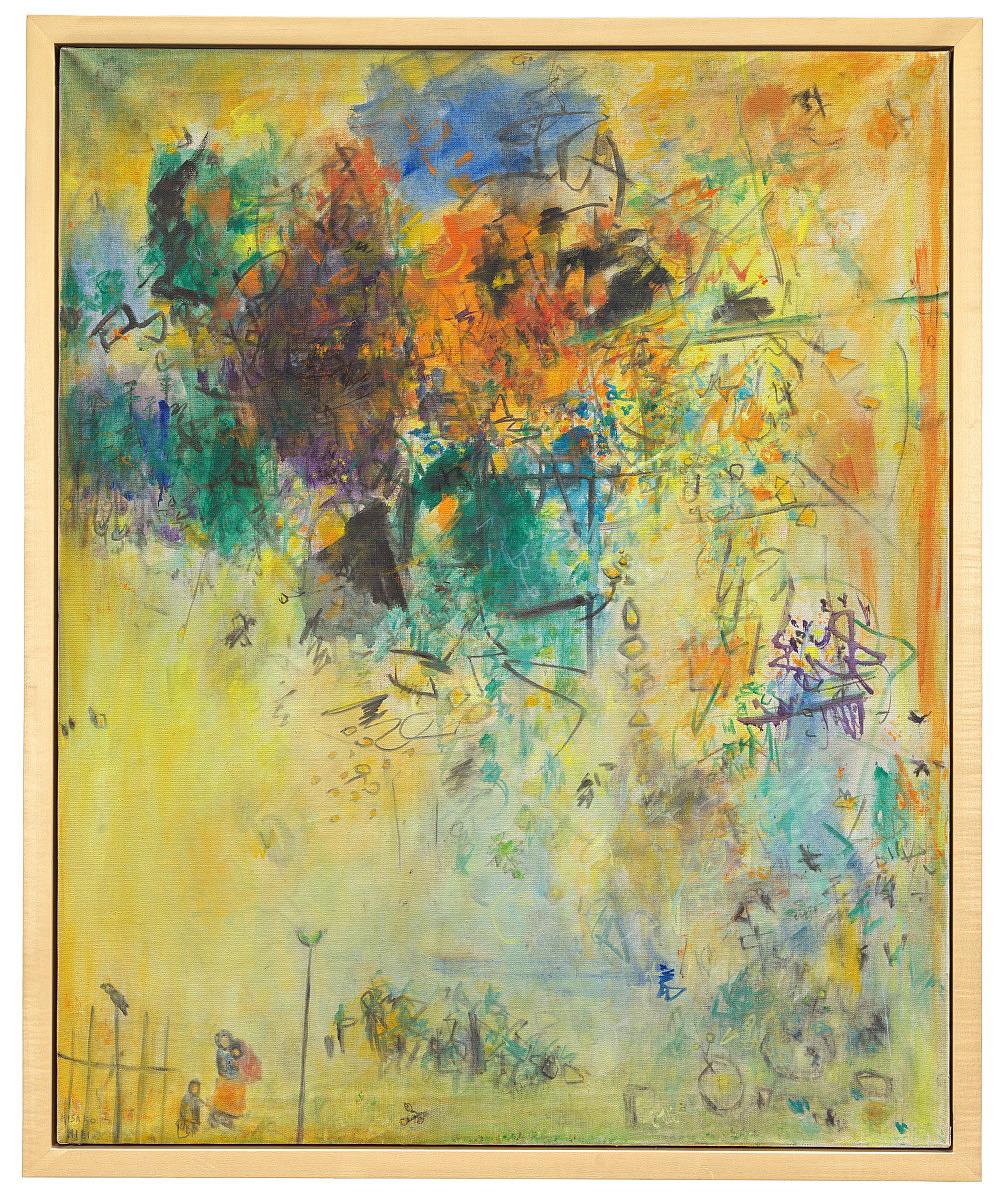

In 1953, after more than 30 years in the United States, Hisako Hibi finally gained American citizenship, thanks to the passing of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act, which made naturalized citizenship available to immigrants born in Asia. The following year, she returned to San Francisco, where she remained until her death in 1991. During the 1960s, her paintings became, in her words, “brighter and much freer” in expression. She experimented with materials and techniques, painting at times with twigs, pebbles and driftwood rather than using a brush. She also looked beyond European painting traditions, for the first time explicitly drawing on Asian aesthetics in her brushwork and compositions. Autumn (1970) is a stunning late work, an almost purely abstract composition whose magnetism hinges on Hibi’s delicate, gestural brushwork and canny activation of empty space. She renders the glory of fall foliage with intense color and touches of the brush that echo Asian calligraphy. Hibi exhibited actively during this period of her life, becoming an esteemed figure in Bay Area art communities. In 1985, the San Francisco Arts Commission granted Hibi an Award of Honor for her achievements.

SAAM is grateful to acquire these rare works from the Hibi family. By entering the museum’s collection, Hisako and Matsusaburo Hibi’s paintings will be discovered by new generations of admirers—whether on display in SAAM’s galleries, on the museum’s website and social media, in open storage, or on loan to other institutions. The impact of such encounters is intangible yet significant. A work of art previously unknown to the general public holds the potential of a revelatory perspective. It offers a window into another human being’s experience and vision and does so across expanses of geography and time. Despite the racial injustice and personal loss they confronted during their lives, the Hibis created lasting works of art in which beauty mingles poignantly with pain, resilience and hope.