In the fall of 2021, I joined the conservators in SAAM’s Lunder Conservation Center to work on an incredible mural painting, Uprising of the Mujeres, by the Chicana artist Judith F. Baca. Baca is one of the most accomplished muralists and narrative artists of our time. She typically creates her murals through direct interaction with the surrounding communities, drawing on their stories to create a site-specific mural. But this mural, being portable, is different. The work challenges the misogyny she encountered as a woman artist, the militarization of the police in Los Angeles, and unfair labor practices for Latinx workers in California, by depicting a powerful Indigenous woman leading agricultural workers in an uprising against their political exploitation.

Feeling that the piece could be incendiary (it is a critical depiction of politicians and the police in Los Angeles), Baca intentionally painted Uprising of the Mujeres on six separate panels of Masonite, a dense fiberboard, so that it could be shown in different contexts and preserved from erasure by graffiti and government officials. Four of the panels were loaded on the backs of trucks and driven around LA, parking in front of locations such as Bank of America and the California State Office of Unemployment, a scene which was captured in the documentary Mur Murs by filmmaker Agnès Varda. Baca says in the film that the juxtaposition of the mural next to a bank and the unemployment office demonstrates, “the separation between the world of work and the world of money.”

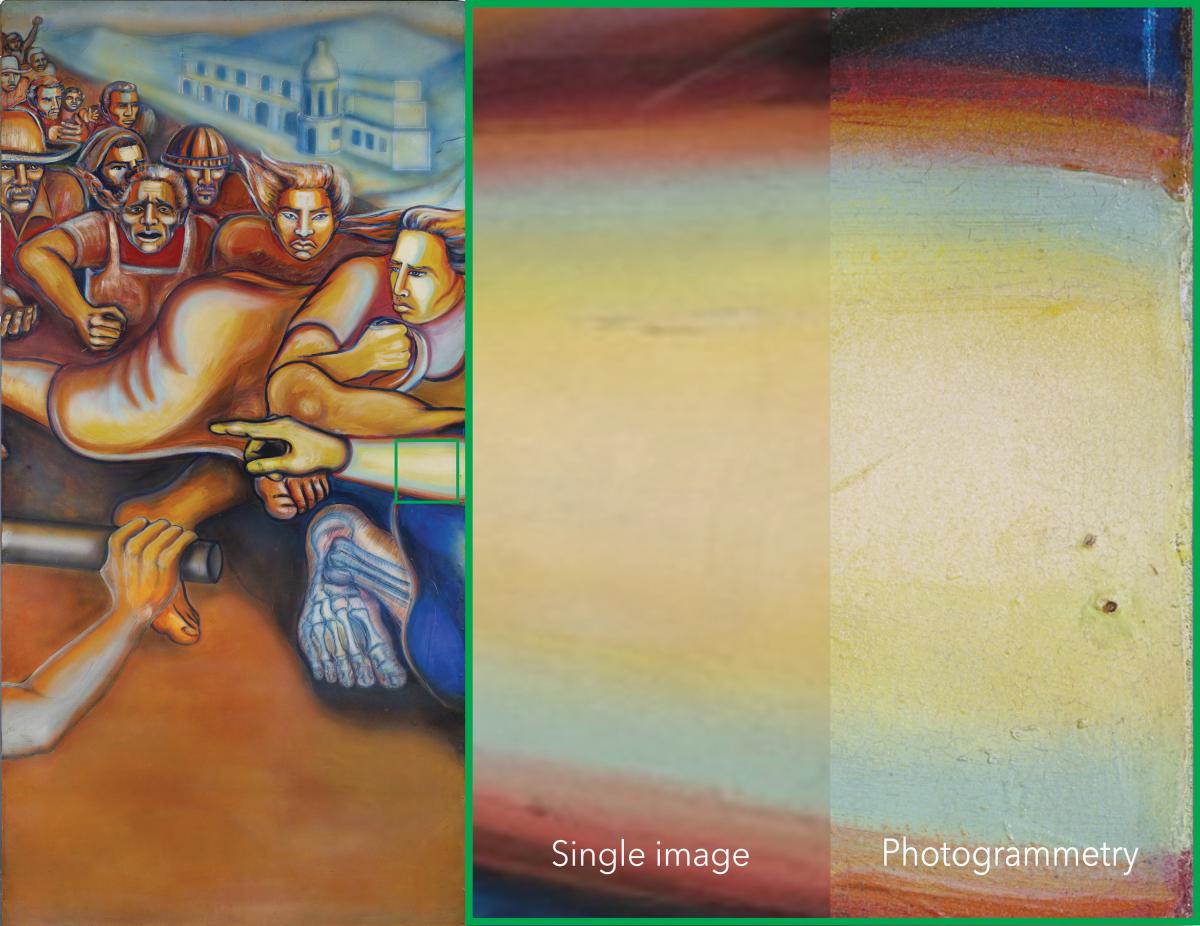

When I began conservation of the mural, I thoroughly examined the panels to understand their condition. The panels were generally stable, despite having been outside at various points, but had a yellowed coating and old retouching that didn’t match. One of the first things I do when beginning a conservation project is to document the object. Typically, conservators attempt to capture an entire painting in a single image in a range of wavelengths of light. However, the large scale of this painting (each of the six panels is 4-foot by 8-foot) means that I’d have to back the camera very far away to capture each, resulting in a very low-resolution image with little detail.

In mural painting conservation, this is a common challenge. Not only are murals big, but they can also be in narrow or difficult-to-access spaces. In order to overcome this, wall painting conservators use a technique called photogrammetry to document murals, a method by which overlapping digital images are captured to generate a photorealistic 3D model. From this 3D model, we can export an undistorted image of the mural at the resolution we chose to capture.

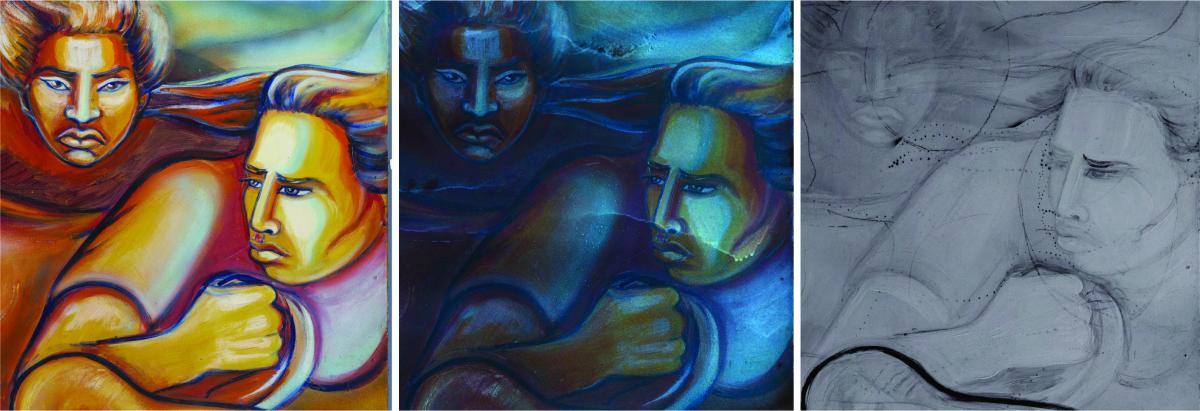

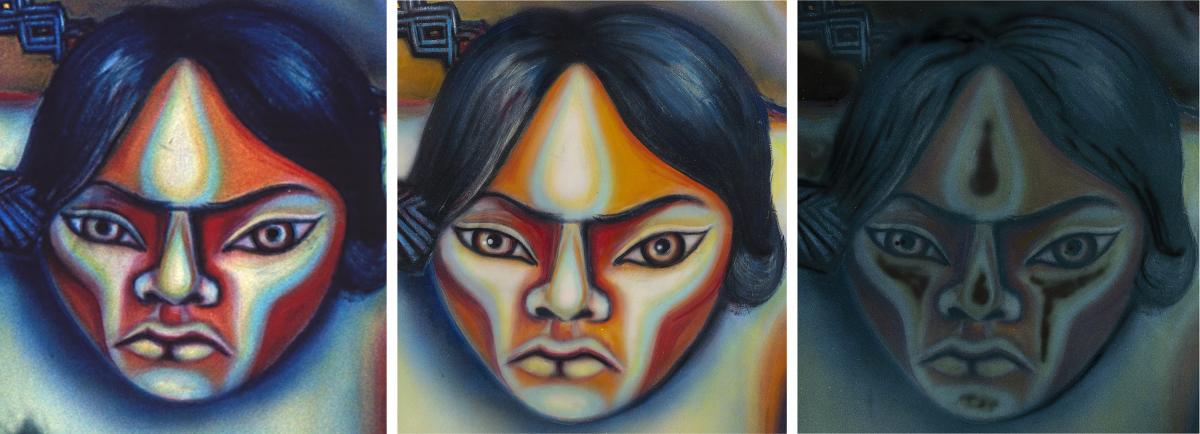

For Uprising of the Mujeres, I captured each panel in three different kinds of light: visible light, ultraviolet induced luminescence, and infrared reflected light using photogrammetry. The visible light records the mural as we see it, front and back. The ultraviolet-induced luminescence excites coatings or pigments on the mural, allowing us to identify and distinguish materials on the surface. Infrared reflected light passes through upper paint layers and is absorbed by carbon-based materials, allowing conservators to see charcoal underdrawings.

This capture process was time-consuming, requiring seven weeks to document each panel completely, but documenting it in this way allowed me to create a high-resolution, undistorted record of the paintings. These images called orthomosaics (as they lack perspectival distortion and are made up of a mosaic of the capture images), can not only be used as a basemap to graphically document condition issues and treatments, they also helped me distinguish between original paint layers, later coatings, retouching, and artistic additions as I cleaned the painting. In UV induced luminescence, the coating applied to the painting emitted light, but the paint that was added later did not. This made these images very useful in separating the original scheme from the later additions and retouching.

These highly detailed images really demonstrated their value when I was looking at cleaning the powerful Indigenous woman leading the uprising on the last panel. When looking at the UV-induced luminescence orthomosaic of this panel in very high detail, I saw two very small dark spots that were not luminescing in each of the figure’s eyes. Their lack of luminescence meant that they were added later, after the piece had been finished and coated by Baca. In visible light, I could see that these dark spots were glints to the eye. I then looked back at the historic photographs and saw that Baca had added these details at least 10 years after the mural had been completed. The added glints really enhanced the figure’s gaze!

This was not just interesting from an art historical perspective; it was critical information to ensure that I safely cleaned the painting. The painting had been made with an airbrushed and hand-brushed acrylic paint and finished with an acrylic coating, but then it was retouched with other acrylic paints over time. Each of these layers was sensitive to the same solvents, so I developed my cleaning approach to only reduce the coating and retouching and not affect the underlying original paint layers. But while I wanted to reduce the yellowed coating on every part of the panels, if I tried to reduce the coating underneath these artistic additions, I would inevitably remove these additions. While they were not ‘original’ to the piece as it was when it was completed in 1979, they were part of the artist’s vision for the artwork and should be kept. For this reason, understanding where the additions were and discerning them from unsympathetic retouching was critical to preserve the artistic integrity of the mural. With this information, I was able to map out where I could not treat the painting and avoid cleaning there.

For this project, photogrammetry and its high-quality outputs were invaluable to plan and undertake mindful conservation treatments. This was also supported by excellent historic images from Judy Baca’s archives, our conversation with the artist about her process, scientific analysis of the materials, and my judgment as a conservator.

Conserving Uprising of the Mujeres was a year-long project funded by the Smithsonian’s Latino Initiative Pool, supervised by Head of Conservation Amber Kerr. Learn more about the history, meaning, and process of making the painting in an interview with Baca conducted by Wendy Rose, project conservator, and Claudia Zapata, former curatorial assistant of Latinx art.