Judith Baca is a painter, muralist, and scholar who works collaboratively within communities to create sites of public memory. Her public arts initiatives reflect the lives and concerns of populations that have been historically disenfranchised, including women, the working poor, youth, the elderly, LGBTQ+, and immigrant communities.

Editor’s note: In this interview, there are mentions of artworks that depict a rape scene and a murder.

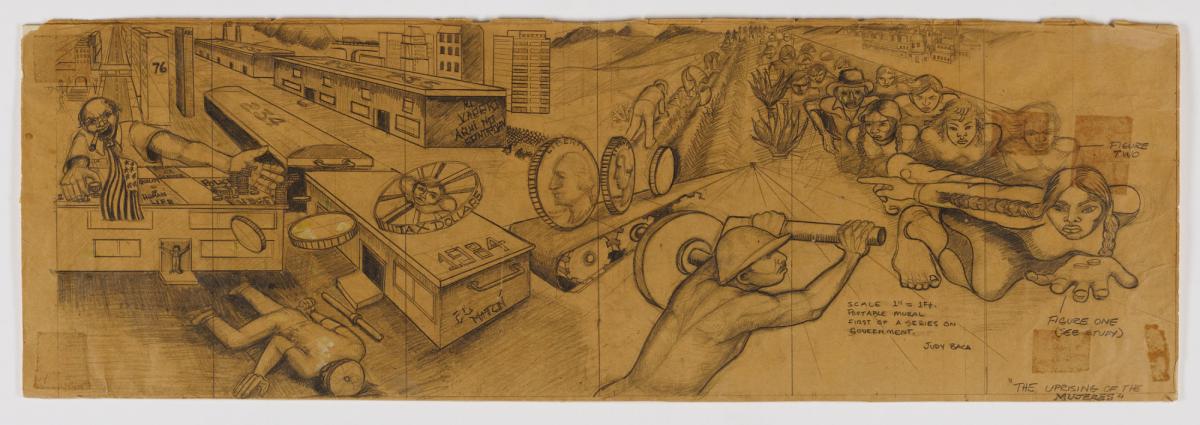

SAAM: Can you tell us what inspired your mural Uprising of the Mujeres?

Judy: In 1977, when I returned to Los Angeles from the Siqueiros Taller [a mural painting workshop in Mexico led by Luis Arenal and Angelica Siqueiros] this mural design, Uprising of the Mujeres, was rejected by the men on my team. The design my team chose was an image about consumerism. I could not participate in the making of the mural; it was an image that looked like a rape.

It was hard for me to believe that they thought it was a good idea. But they felt that women were the basis of consumerism, as the new family leaders of economics; therefore, they were the ones to blame for all its perceived evils. Their design was a critique of consumerist policies and practices, in the sense that, very much like Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco's piece Catharsis in the Palacio de Bellas Artes, it was an image that blamed women. In the case of Orozco's amazing artwork, the woman is at the basis of war, and in the case of the team in Taller, she's at the basis of consumerism. Since I was the only woman in the workshop of twenty-two men it was hard to find support for my position.

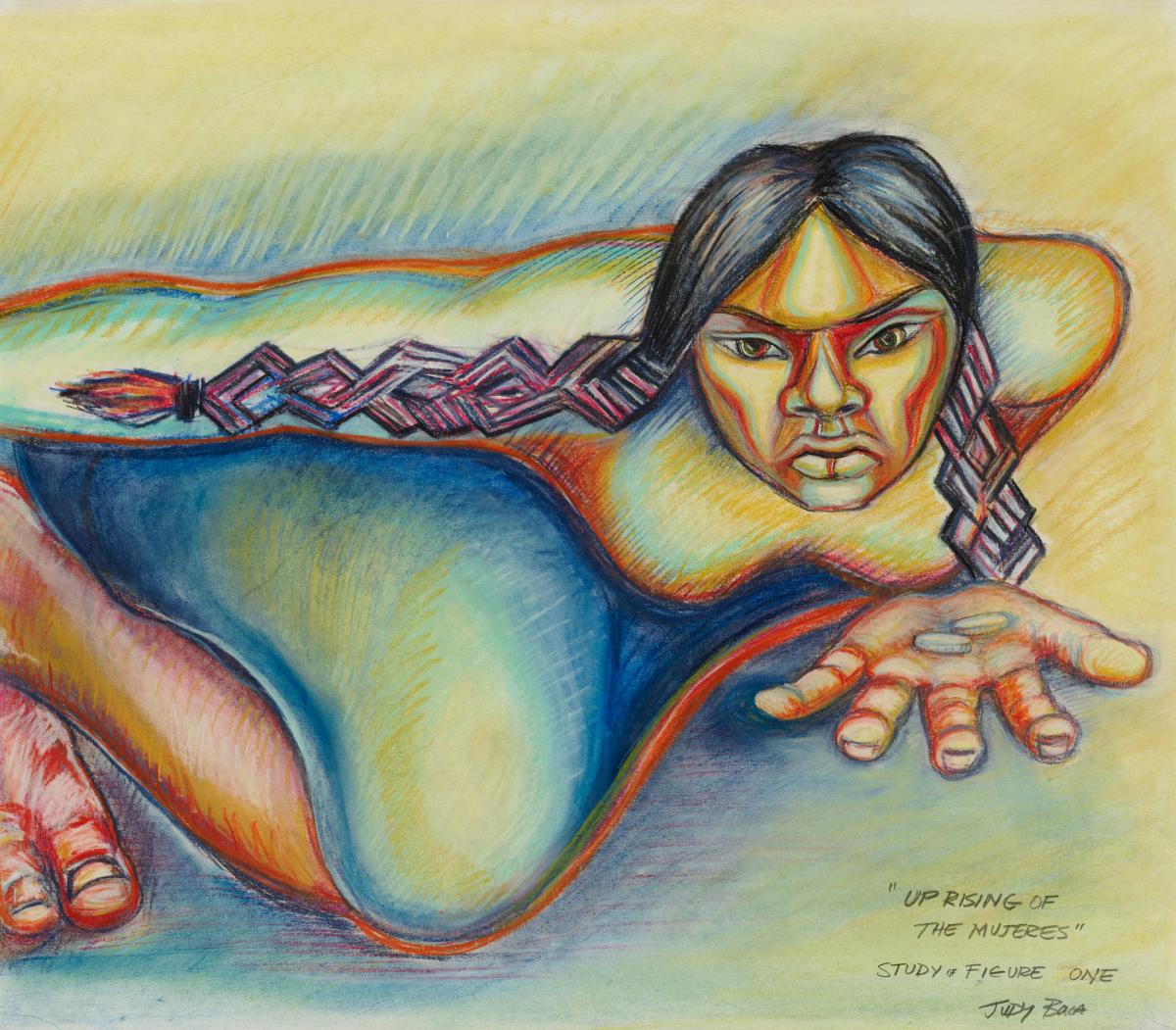

I designed an alternative image that was rejected. There was only one man on the team that supported my idea of a powerful Indigenous woman coming out of the fields. He was a Chicano from south Texas. I was encouraged by him. When I came home, I finished the design and put it on panels, very similar in terms of scale to a mural, and painted it at the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) in LA.

Compared to your other site-based murals, what was the rationale for making Uprising of the Mujeres portable?

That piece could not have gone on to a public wall in a neighborhood at that time. It would have been censored. It would end up with police hanging out in front of it as they had done in other cases where they did not approve of an image. In fact, I would venture that it's still not possible today. Uprising has the projects lit by the lights of police helicopters and a dead body strewn in projects. The buildings show the numbering system used to identify the homes from the air.

I had just written an article for UCLA called “Birth of a Movement,” where I chronicled a number of times that muralists sponsored by SPARC produced works that were essentially stopped by the police department. They weren't violent and bloody images, they were simply critical of the police, for example, and that was not possible. A mural produced in 1997 by the artist Noni Olabisi depicting the Black Panthers’ community sickle cell and food programs, along with Huey Newton and other armed members, was brought before the arts commission over twenty times because the Panthers were not acceptable. It was as if Olabisi was bringing them back to life. So, there are certain kinds of works that couldn't go on a public street, and the portability gave me the opportunity to place it on nobody's wall, on a wall that could move, and then it could be then seen in different neighborhoods.

Why did you choose to paint the mural on Masonite?

It was cheap. You paint with what you know, in the Chicano aesthetic rasquaschimo, which is “you use what you got,” right? One time I painted this piece about one of the [neighborhood] boys being murdered, and it was a very emotional piece. I didn't have any paper, so I just gessoed newsprint. You have to make do with what you've got, and the Masonite was pretty durable material. I could put backing on it with wooden braces and keep it from warping, which was my big concern. It wasn't so heavy that I couldn't move it around, and it had a lot of good characteristics.

Can you walk us through how the panels were painted?

First, I gessoed the surface. For that part, I was working alone most of the time. I could get help at the point when I was transferring [and] then blocking out the design, but in in the creation and scaling of the design, that process would have been more solitary. I had a large compass, and I would draw images using circles that kept it from being too mechanical and making it more fluid. At that point I used a pouncing wheel to perforate the paper and transfer the design on the board. Then I started to block it in and paint. In some cases, I tried to spray paint in the base layer, which wasn't so successful. I spent most of my time trying to make the spray gun work with acrylic paint - before acrylic paint was made for airbrushes - and gave up on it and went back to hand painting with a brush. I used a dark tone, a middle tone, and a highlight, and then came in to do finish work with finer painting.

Do you recall how long it took to paint the mural?

Well, I came back from the workshop in 1977 and in 1978 I was working on the Great Wall of Los Angeles, so probably I didn't get back to it [Uprising] till 1979. I would say it took a year of painting off and on, with me trying to earn money in between because it wasn't funded.

Who do you see as the audience or audiences for this mural?

The audience for the work, initially, was probably the audience for all my work: the local community. I painted it in 1979, so it was at the height of the mural movement in Los Angeles. If you look at the piece, it's actually directed at people in the neighborhoods. Particularly, the phrase “mi varrio aqui no controlan” which I represented as graffiti in the mural. It was a speak-back to the gang groups that I was working with, because [the gangs] wrote everywhere “aqui controlan"—that they controlled the neighborhoods—and it was me saying to them “no you don't.”

And of course, the farmworkers and the laborers are turning the money machine in the fields and have become increasingly the labor force that is creating wealth for some, but for our people, poverty, pesticide problems, and other things that have accompanied the farm workers. It was about the fact that the city council in LA was directing money into police enforcement, creating a kind of militarization. The 1970s was a time in which LA shifted from community policing to helicopter observation. That was a terrifying moment. People were coming in from El Salvador and Central America, and these helicopters started running rampant all over our neighborhoods and terrifying them because helicopters were seen as of modes of death delivery in Central America. So yeah, all the content is directly speaking to neighborhood people, and particularly the youth. We got kids dying at an enormous rate out there in inter-neighborhood warfare. I have one fallen in the foreground and it's all lit by the light of a helicopter.

How do you feel about the mural now being part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s permanent collection?

I think it’s a really great thing, because something occurring today that hasn’t happened historically, is that there is concern on a national level about what is happening in these neighborhoods, in barrios of LA. As our [Latinx] population has increased, we become a larger group of participants within the civic dialogue of America, and people understand that we are, in fact, important to the American story. This story is really everyone's story, an American story.

This interview took place in February 2022, as part of a year-long conservation project funded by the Smithsonian’s Latino Initiative Pool. Baca spoke with Wendy Rose, project conservator, and Claudia Zapata, former curatorial assistant of Latinx art, about the history, meaning, and process of making Uprising of the Mujeres, which was acquired by SAAM in 2019. This story has been edited from a transcript of their conversation for clarity and length.