Laura Aguilar (1959-2018) was a Chicana photographer known for black and white portraiture commemorating her intersecting Latinx and LGBTQ+ communities. Chicanx and Latinx scholars have long celebrated Aguilar’s photographs for her focus on disabilities, gender, race, sexuality, and beauty, demanding a rightful place for the artist within the history of American photography. Overlooked by the mainstream art world during her lifetime, she has received posthumous success with a recent critically acclaimed retrospective that was shown in Los Angeles and New York as well as major acquisitions by museums including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Vincent Price Art Museum. SAAM is acquiring 21 photographs by Aguilar, including the complete Latina Lesbian series. Aguilar’s photographs join urban Latinx documentary photographers such as John Valadez, Frank Espada, and Hiram Maristany that are well-represented in SAAM’s collection. Like these photographers, Aguilar’s oeuvre is a community-focused practice that calls attention to marginalized groups, reframing their interpretation while also highlighting the artist’s personal connection to these spaces as a form of arts activism.

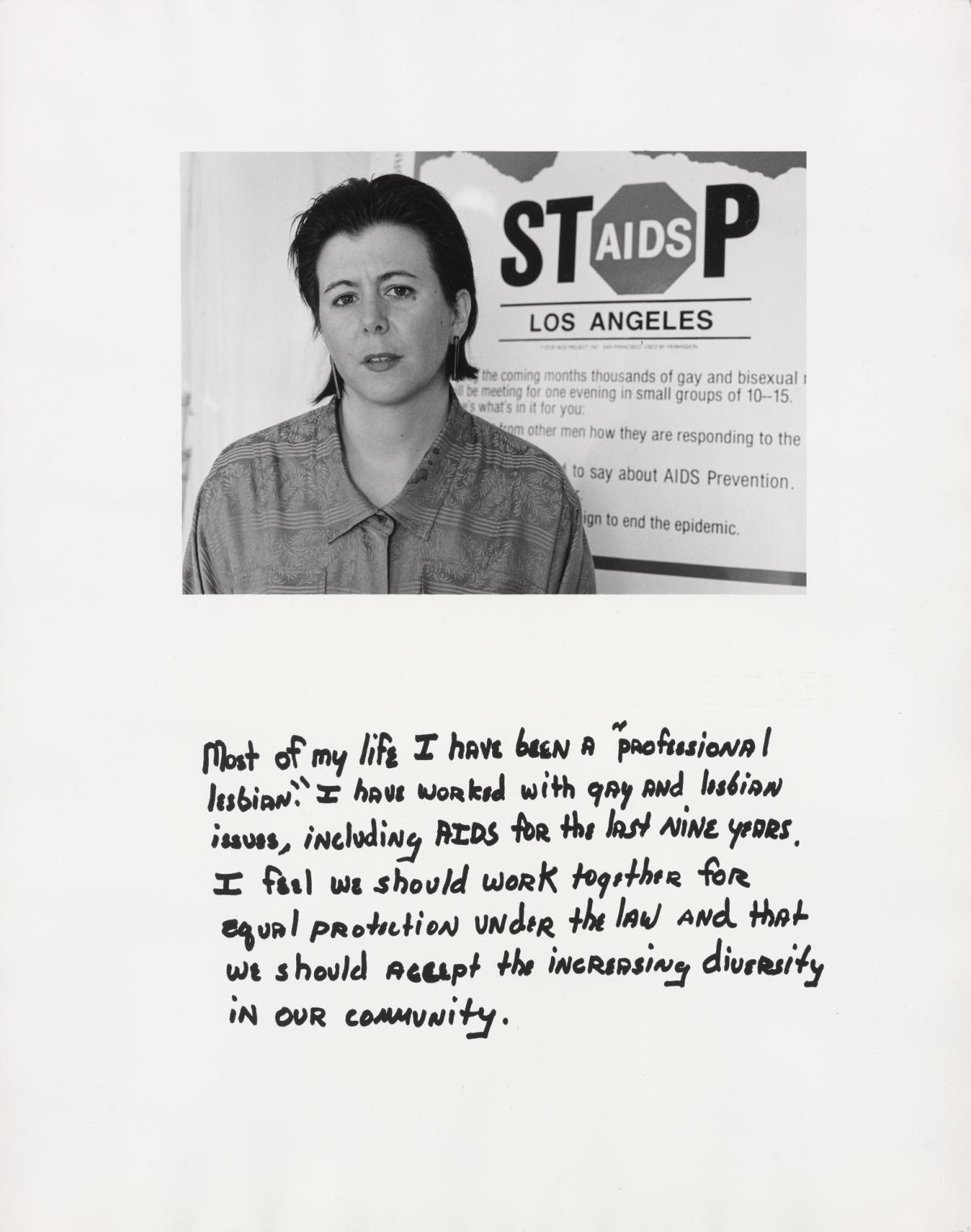

In the series Latina Lesbians (1986-1990), sponsored by Los Angeles’ lesbian social services center Connexus Women’s Center/Centro de Mujeres, Aguilar focuses on the Latina lesbian community. She defined the objective of the documentary series as a “vehicle to educate,” empowering the lesbian sitters to represent their desired identities. Among her subjects are several queer professional women captured in their preferred fashion and chosen environments. Aguilar includes a handwritten statement with each portrait as a method of further connectivity and relatability to the sitter. Varying in length, these responses humanize the sitter, contextualizing their journeys and the evolution of their intersecting identities. Portraits like Carla Barboza include a declarative response: “I used to worry about being different. Now I realize my differences are my strengths.” While some responses represent the sitter’s realized self and journeys to self-acceptance, other portraits and accompanying statements act as unresolved confessions by the sitter. In Aguilar’s own series portrait, Laura A, she grapples with the definitive nomenclature meant to capture her sexuality:

As a result of her auditory dyslexia, Aguilar explored her own method of verbal and written communication throughout her work. While her Latina Lesbian text evokes discomfort with her position within the queer community, she couches her portrait and her textual contribution within her predilection for play. Framing her image with lotería squares from the bingo-like games played within Mexican and Mexican American cultures, Aguilar embeds her likeness within this unique ornamental frame, distinguishing her portrait design from the others in the series. Her represented space is punctuated by her toy collection featured in each corner of the frame, cherished objects that would emerge throughout her work.

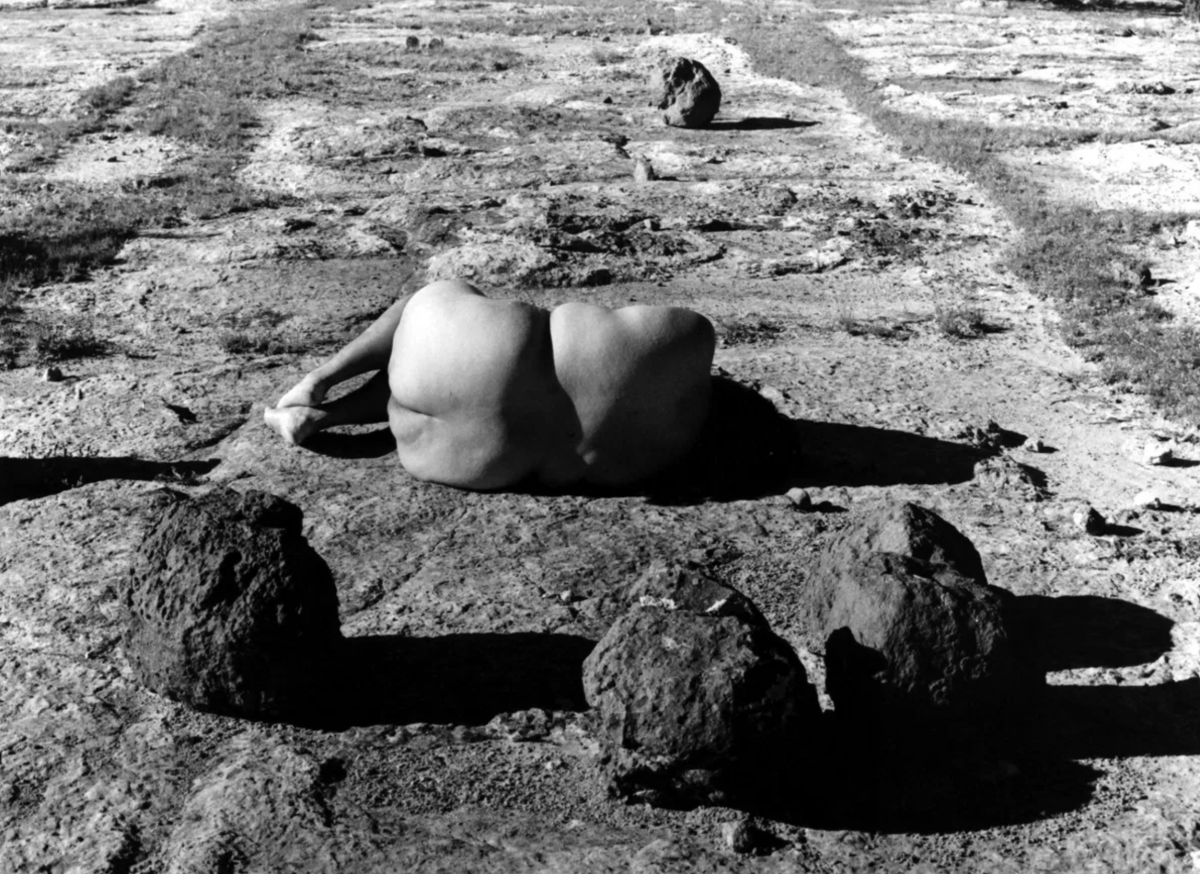

Aguilar’s ongoing tension and reclamations of her own identities are constant throughout her artwork. Most notably, she uses her nude body to reclaim her self-identified fatness. She subverts the erotic and racialized ways white nude women have pervaded art history and repositions her fat, brown body as an object of desire. Her first foray into nudity as a central strategy is In Sandy’s Room (1989). The scene captures Aguilar calmly sitting in repose, cooling off in front of an electric fan at a friend’s home. The breadth of Aguilar’s subsequent nude works covers a divergent range of emotions, where she continually experiments and challenges the perception of her body’s aesthetic. For her iconic Nature Self Portrait series (1996), she looked to other women photographers, like Judy Dater’s nude work in the Badlands, as inspiration to merge her naked body with the natural world. Set against the backdrop of Cubero, New Mexico, Aguilar’s Nature images emphasize the draping of Aguilar’s body and the parallel undulations of the terrain. In Nature Self-Portrait #12, she contorts her body to mimic the surrounding boulders, casting a similar shadow that punctuates the landscape. These corporeal reconfigurations adjust perceptions of monumentality and beauty, where Aguilar’s body is equally as breathtaking as the landmarks she inhabits. By placing herself in this geography, she dismantles the historic depictions characterizing the emptiness among western landscape views which symbolized Manifest Destiny and America’s westward expansion.

With SAAM’s recent Laura Aguilar acquisitions, visitors and scholars will have a unique opportunity to experience the many pivotal contributions Aguilar’s work makes to the art world. As a disruptor of normative standards of beauty and a queer community translator, she is one of the most influential Chicana photographers of her generation, and her presence at SAAM helps us properly tell the multifaceted story of American art.