Much like the Hippocratic oath taken by doctors to do no harm, conservators are guided by a parallel ethical code in their work. There are instances when addressing the challenges of a conservation treatment fall outside the limits available, and on such occasions, the best solution can only reveal itself over time, with the patience and expertise of professionals and the future development of science and technologies.

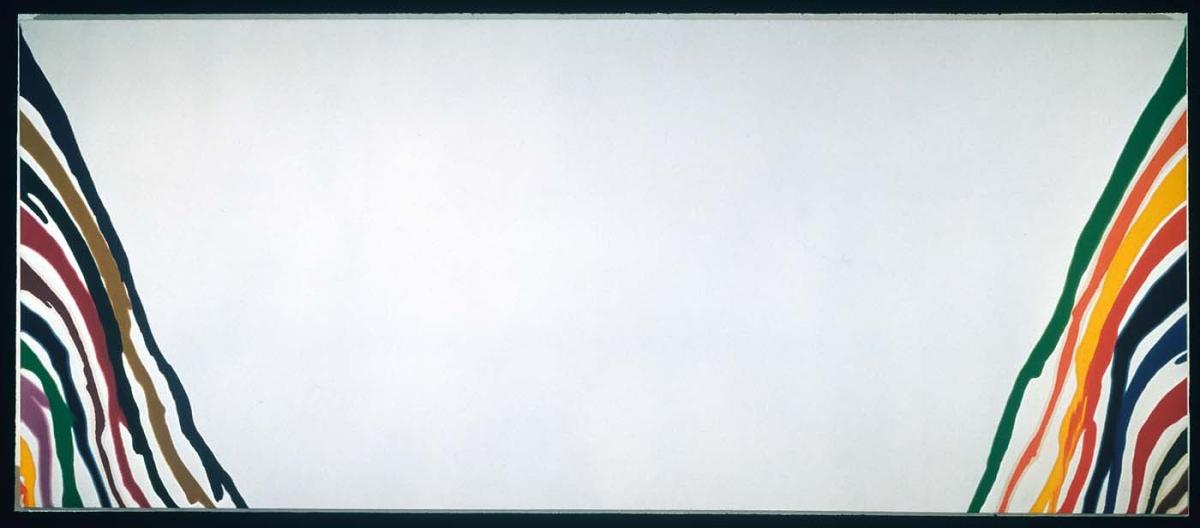

Such was the case with the treatment of Morris Louis's monumental painting, Beta Upsilon. Louis was a pathbreaking figure in American color field painting. A native of Baltimore, he settled in the Washington area in 1947, and was one of the first artists to bring national attention to Washington’s art scene in the late 1950s. Louis created majestically scaled yet delicate compositions by pouring diluted acrylic paint across the surface of raw canvas, staining the fabric with gravity-bound waves of color.

He completed Beta Upsilon in 1960, less than two years before his death at age 49 from cancer. It is a glorious and daring painting, more than 20 feet long, yet has been out of public sight for more than three decades. This is because, until recently, the technology did not exist to address two approximately 31-inch-long graphite marks left by a visitor that blemished the expansive middle section of the unprimed painting.

Conservators serve as the caretakers of a museum's collections, with their primary mission being the preservation of our cultural heritage. The field of conservation relies on a deep understanding and knowledge of science, art history and the studio arts. To determine the safest treatment for this artwork following the incident in 1988, the conservation team consulted with many specialists—including scientists from the Smithsonian conservation research team and conservators and art historians from other institutions. After extensive research, testing, and analysis, no viable options could be immediately identified to remove the graphite marks without causing damage to the raw canvas. This prompted the difficult decision to keep the painting off view until science could catch up with the problem.

Over the next three decades, conservators researched new treatments presented in the field, with the use of lasers showing the greatest promise. Early versions of lasers were too powerful, however, and could only be used on inorganic surfaces such as stone and metal. These lasers would cause organic materials such as cotton to dehydrate and scorch due to the light energy levels of the infrared lasers. It was not until the last decade that new laser systems were developed in light ranges more suitable for use in the conservation of organic materials.

In 2017, SAAM Head Conservator Amber Kerr began a collaborative research project with Bartosz Dajnowski, an object conservator who specializes in the use of lasers. Their cutting-edge research led to a newly patented laser by G.C. Laser Systems designed to remove material from a textile without causing damage. The laser was customized to specifically address the removal of graphite marks from Beta Upsilon using isolated energy in the green range of the light spectrum. Initial testing also revealed that the laser was effective at removing airborne pollutants that had accumulated on the surface of the raw canvas over time, causing a greyish look to the surface. The light energy emitted from the laser was just strong enough to cause the unwanted graphite and accumulated pollutants from the air (both carbon-based) to ablate, or break apart, and be simultaneously extracted from the surface, without causing even a thread of the fabric to be disrupted.

Numerous tests were undertaken before the laser treatment was applied to the painting itself. The process was meticulously documented, photographed, and analyzed at each stage to record and monitor the results. This careful planning, research, and development of new technology has led to the successful full treatment of Beta Upsilon and the return of the painting to public view. After 35 years, the painting is back in SAAM’s galleries for visitors to enjoy, and the conservation field has a new tool for treating paintings on unprimed canvas.

Anna Nielsen is program coordinator for SAAM's Lunder Conservation Center.

Note: This story has been updated to correct the length of the graphite marks.