Rowland Ricketts (b. 1971, resides Bloomington, Indiana) creates immersive installations using handwoven and hand-dyed cloth. His holistic artistic practice begins on his farm, where he cultivates the indigo plants he uses to color his artwork, fully linking his material and process with the finished product. Ricketts often incorporates participatory engagement from non-artists, emphasizing the relationship between nature, culture, the passage of time, and everyday life.

For the past two decades, indigo has been Rowland Ricketts’s primary medium and subject matter. Ricketts uses natural dyes and historical Japanese processes to create contemporary artworks that engage visitors in multisensory experiences and embraces indigo’s depth of meaning. Using an approach that inextricably links process and outcome, Ricketts works with a “farm-to-gallery” concept, an idea more often associated with the craft food movement. He farms his indigo on six acres in Bloomington, Indiana, where he also serves as associate dean of the Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture, and Design at Indiana University.

Techniques Ricketts learned during apprenticeships in Japan, and while operating his own indigo farm there, drive his woven objects and installations. These often incorporate soundscapes composed by frequent collaborator Norbert Herber, which use documentation of the process—crinkling of leaves, wind in the field—or tones derived from the variation of shades of indigo as sonic building blocks. Ricketts also integrates participatory engagement from non-artists into his practice, making the case that indigo belongs to everyone.

On the Blog

Eye Level, December 2, 2020, “From Indigo Farm to Art Gallery with Artist Rowland Ricketts”

Ai no Keshiki – Indigo Views

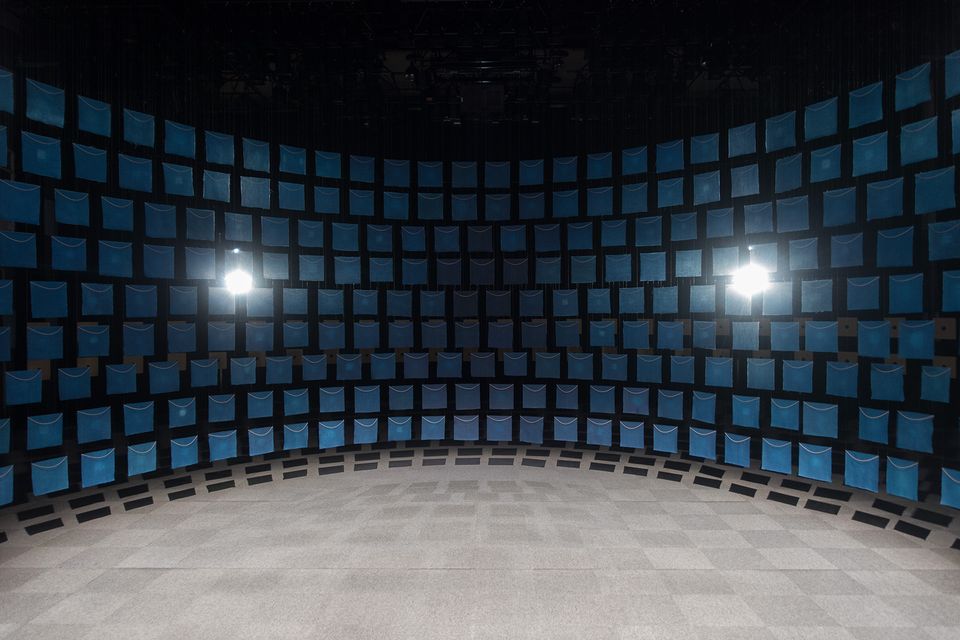

Ai no Keshiki – Indigo Views was originally developed in Tokushima, a Japanese prefecture where Ricketts spent time apprenticing with indigo farmers and dyers in the late 1990s. Reconfigured for the Renwick Gallery, this installation is the result of many collaborators. In the summer of 2017, 450 people from ten countries volunteered to live with a small length of cloth dyed with Awa indigo, a varietal native to Tokushima. Now in this gallery, the indigo cloth was placed in hand-crafted wooden boxes with a small central opening to allow light to penetrate, bearing witness to the everyday moments of each participant’s life. Variations in color, resulting from the intensity and frequency of light exposure, are a testament to this diversity of experience.

These subtle distinctions tie directly to the work’s title, which roughly translates as “love for keshiki,” a Japanese philosophical concept centered on the landscape or “scenery” of an object. Through the lens of keshiki, the fading of bright blue indigo isn’t a loss. Instead, it speaks to the way things inherently change over time, offering new scenery with each engagement.

Collection of the Citizen’s Cultural Division, Tokushima Prefectural Office, until each cloth is returned to participants

Indigo as Sound

Rowland Ricketts with Norbert Herber and 450 participants, Ai no Keshiki – Indigo Views, 2017–18 and 2020, faded indigo cloth and sound, dimensions variable, Collection of the Citizen’s Cultural Division, Tokushima Prefectural Office, until each cloth is returned to participants. Installation view, Tokushima Prefecture, Japan, 2018. Photo by Rowland Ricketts

Rowland Ricketts with Norbert Herber and 450 participants, Ai no Keshiki – Indigo Views, 2017–18 and 2020, faded indigo cloth and sound, dimensions variable, Collection of the Citizen’s Cultural Division, Tokushima Prefectural Office, until each cloth is returned to participants. Installation view, Tokushima Prefecture, Japan, 2018. Photo by Rowland Ricketts

The sound for Ai no Keshiki – Indigo Views comes through speaker cabinets repurposed from the boxes used to fade each indigo-dyed cloth. What you hear isn’t pre-recorded and played back, but an algorithm composed in real time. Notes are shaped by the same factors that impact the visual construction of this installation. For example, data in the form of ambient light measurements impact the tempo of the piece. “Bright” values increase tempo while “dark” values slow the composition down. The sound is shaped by the infinite variation in color and light in this very room.

The composer, Norbert Herber, describes the sound this way:

This music contains opposing sonic volumes. One is opaque and heavy; it fills the space around your body and would feel warm to the touch. Another can be heard just “above” that is lighter and semi-transparent, marking the passage of time with rhythmic pulses. Yet another floats above the rest. It sounds bright, almost brittle, and is in dialogue with the other voices telling a story of this moment, and the next, and the next, with no end.”