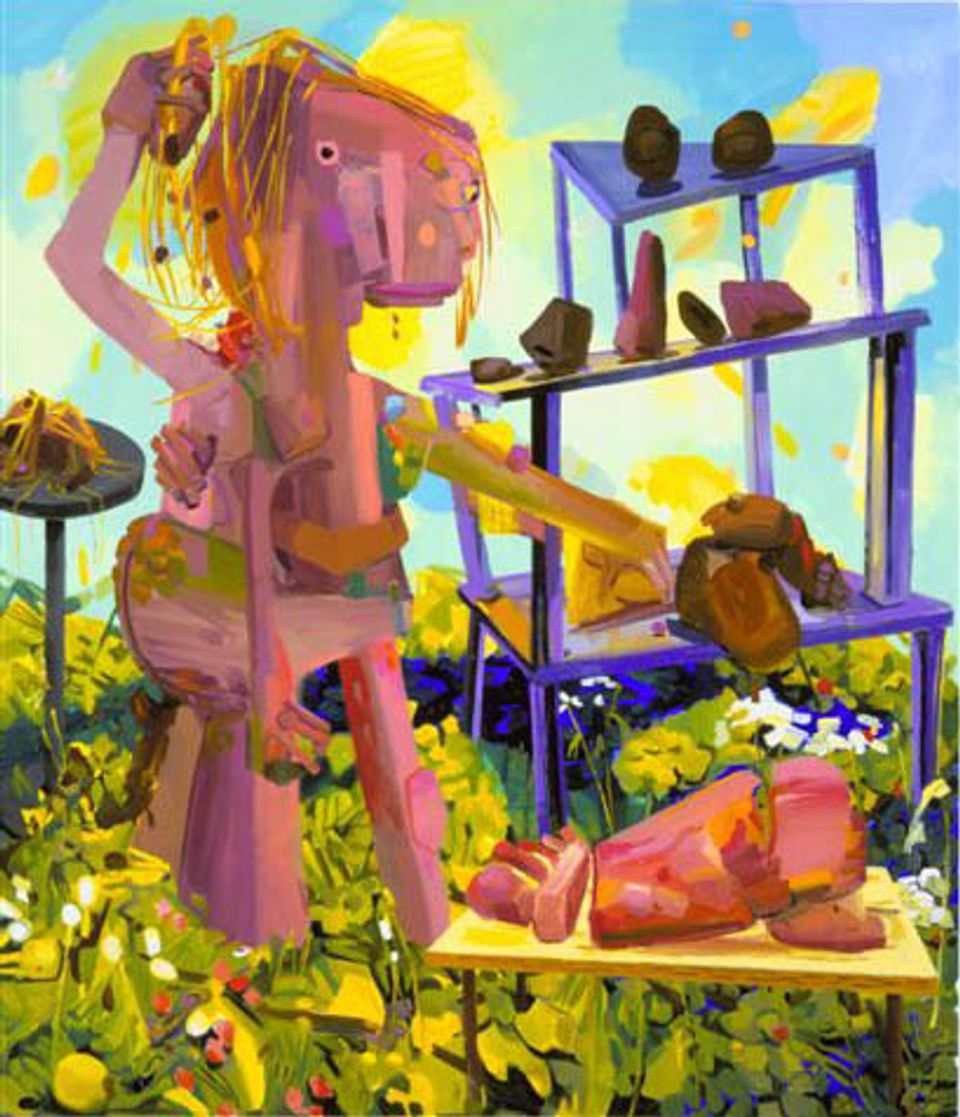

Dana Schutz, Twin Parts, 2004, Zach Feuer Gallery

Economist Tyler Cowen mentioned that he's still thinking about Dana Schutz's paintings after a recent tour through MoMA. There's been no lack of attention for Schutz since 2003, when her works were featured in both the Venice and Prague biennales—just one year after her graduation from Columbia's MFA program. From 2003 to 2004, sales figures for her paintings rocketed roughly from four to six digits, which speaks to her presence in the New York art world—as does her recent entrance into the MoMA contemporary collection. These facts, of course, can cloud the way that we think about an artist; discussions about Dana Schutz are centered around her rising star as often as around her art.

Cowen's post made me think back to this post from Edward Winkleman's archives, a post that led to a lively discussion about Schutz's work. One commenter in that thread cleverly describes Schutz as "Ensor on vacation in Tahiti with Gauguin." Tyler Green chimes in with a claim he's long maintained: that (despite the artist's East Coast residency) her style is deeply indebted—too deeply indebted—to Bay area figurative giants David Park and Elmer Bischoff.

Ask about her work and people will tell you either that she's a phenomenal painter or more phenomenon than painter. The divide only grows sharper as her prominence rises. I think the question in part turns on the flatness of her images. Occassionally the seams in Schutz's mise en scène are too apparent, fraying into a few distinguishable layers of brushstroke. But more often than not she succeeds, her marks operating freely and aggressively but still convincingly within one plane. Depth in these works is the product of Schutz's deft use of color.

The artist's humor is often noted: Her tropical cannibals, choppy surgeons, paranoid patients, and self-devouring figures neatly anticipate the process by which viewers and critics scan her works and disassemble them into component influences. Those influences are there, from the overarching presence of Gaugin in Schutz's palette to the art-historical hat-tips in her compositions. (Winkleman notes references to Ensor and Rembrandt in Schutz's Presentation, to list one example.)

Wit isn't the only narrative handhold to Schutz's work. The character in Twin Parts, pictured in the process of building itself from spare body parts (or taking itself apart) seems engaged in a painterly process—building an image to portray the self. That construction metaphor also hints at the way we interact with one another and the commercial world, a theme put forward in Surgery and her paintings of "self-eaters." While I don't think it's necessarily a central element to her work, there is a current of feminist criticism in Schutz's treatment of our bodies and ourselves.

Remarkably, Schutz is still under 30. (It's almost understandable that some people spite her for her success.) Those who aren't fans may find that she'll surprise them down the road, of course, but either way, they ought to get comfortable with seeing her work around.