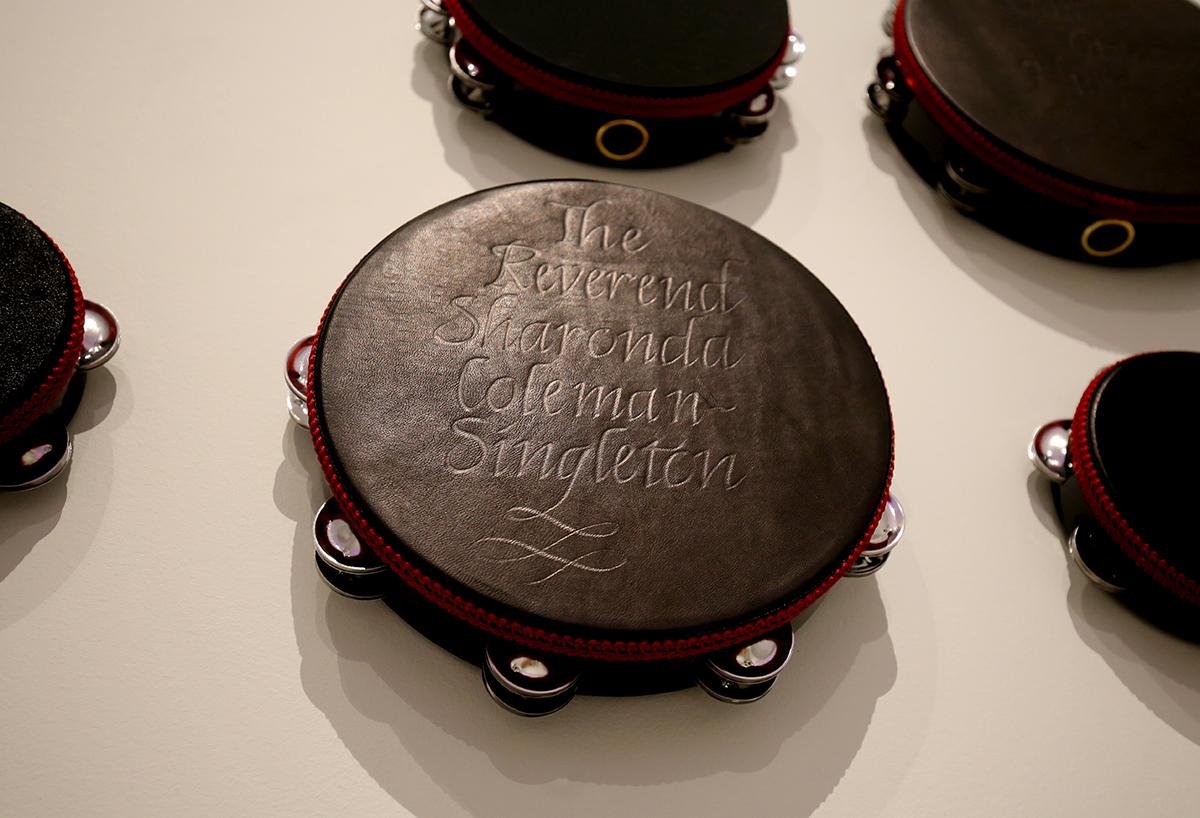

The other day, my colleague, Libby, and I walked through the museum in search of an artwork we could talk about. In addition to her work in the museum's technology office, she's an artist and photographer (if you're a reader of Eye Level, you've seen her work!). We chose the third floor that houses modern and contemporary art. And though each artwork has a story to tell, Lava Thomas's Requiem for Charleston, the artist's response to the church massacre at Mother Emanuel in 2015, spoke the most to us, in a quietly powerful way (if such a thing is possible). The artwork is comprised of a series of mostly black lambskin tambourines into which Thomas has burned the names of the victims using pyrographic calligraphy. Other tambourines are left blank, while a few are made of acrylic. The artwork is mounted on a wall at one end of the gallery, a few steps from a large window, that brings in a bit of natural light.

"This is one that I feel like you could walk past and not know what it’s about," Libby began. "But if you stop for a few seconds you start to see the names emerge. Of course that’s the powerful part of this. It’s subtle and beautifully done. The shiny [acrylic] ones are at different heights for a child, a teenager, and an adult to see. Everyone who views this can see themselves reflected. The artist put a lot of thought into this. Yes, it’s shaped like a diamond but it’s also a cross which goes back to the church. She put it on tambourines which is powerful, because tambourines normally make sound, but they are silenced, the way these people’s voices are silenced."

We talked about the news and how too often we open our laptops and are confronted by tragedy. But there's something about this piece that takes on larger meaning when you stand in front of it, then get up close and see a bit of your own reflection. "I know I’m supposed to be sad when I see this," Libby continued, "and I am, but I think it’s kind of hopeful, too. Maybe that’s a crazy thing to say. The blank ones seem like a call to action: what are you going to do to change it? Is this one going to turn to leather with another name on it, or is it going to change and maybe it’s going to be taken off the wall and you’ll be able to play it. Is it going to be something joyous? What is the future going to be about?"

What will the future look like, and what will it sound like? Music, silence, or something in-between? It was hard to walk away from this one, but eventually we did, leaving the powerful artwork behind, but not the thoughts and emotions it evoked in us.

Requiem for Charleston is currently on view in the Smithsonian American Art Museum 3rd Floor East Wing Lincoln Gallery.