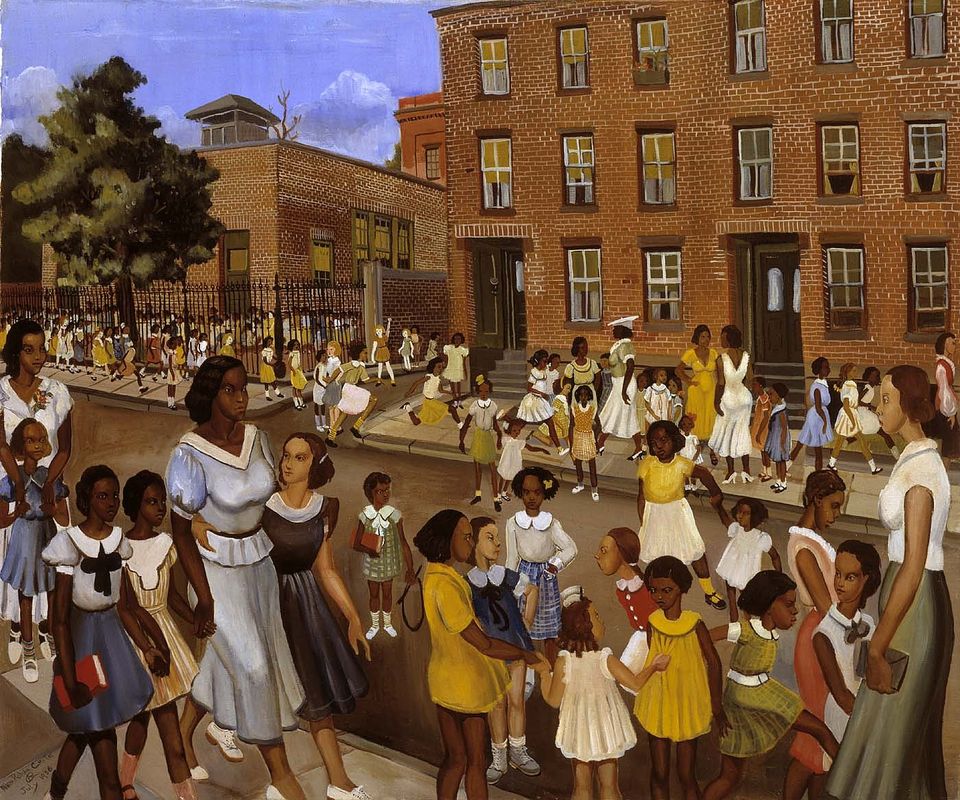

Allan Rohan Crite (1910–2007), School's Out, 1936, oil on canvas, 30 1/4 X 36 1/8 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the Museum of Modern Art, 1971.447.18

Student Questions

1. Focus on a group of three or four figures in School’s Out. What are those people doing?

2. What do you notice about the buildings and street?

3. Why do you think Crite paints this scene in a “documentary style”? Does his approach fit the subject? If so, how?

About This Artwork

With his vibrant painting of urban life, Allan Rohan Crite provides a wholesome portrait of a community. On a sunny afternoon after the last bell, mostly African American girls, neatly dressed, spill out of the fenced yard of a city school. Most stroll with friends, some break into a run, a few quarrel, and a handful walk with their mothers. Prim collars, puffed sleeves, and full skirts are the fashion, yet no two figures wear the same outfit or hairstyle, emphasizing each person's individuality. The school is in good repair, the sidewalks are clean, and the apartment building next to the school is well kept. Even though Crite made his painting amid the Great Depression, there are no signs of poverty or struggle. This community is pictured as solid and strong, bubbling with optimistic energy on a crystal clear day.

Crite grew up and worked most of his life in Roxbury, Massachusetts, a neighborhood in Boston, which became by 1960 the center of the city's African American community. He was especially well known for paintings describing the social and religious life he observed around him. But Crite, who saw himself as a type of history painter, said that his work was also about something larger. "I am ... a storyteller of the drama of man. This is my small contribution—to tell the African American experience—in a local sense, of the neighborhood, and, in a larger sense, of its part in the total human experience." While School's Out may be based on a scene the painter witnessed, Crite also implies that this scene is typical at any number of schools in urban, mostly black neighborhoods in the late 1930s.

In American cities in the 1930s and 1940s, most schools were segregated, partly by law, partly by custom, and partly by choice. Most African American leaders and parents believed that a good education was the key to a better life, and black people pulled together to provide their children the best schooling possible. With School's Out, Crite suggests what many of his neighbors believed: where communities and schools are strong, African American families can lead dignified, productive lives despite segregation.

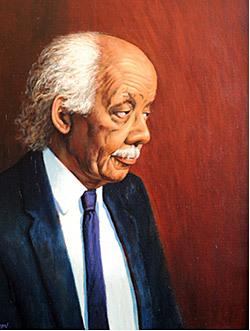

About This Artist

Allan Rohan Crite (born Plainfield, NJ 1910–died Boston, MA 2007)

Allan Crite was a painter, illustrator, librarian, and writer whose work explored the African American experience in and around Roxbury, Massachusetts, the Boston neighborhood where he lived almost his entire life. He attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and spent one year as a Works Project Administration (WPA) artist. In 1940, he took a job as a draftsman for the Boston Ship Yard, a position he held for thirty years. He later worked as a librarian at Harvard University. While working, he attended Boston University and the Massachusetts College of Art before completing his studies at Harvard University. Crite created art and literary works inspired by Negro spirituals, religious themes, and his neighborhood, saying that he had three aims: to focus on “black people in this city as I saw them,” to convey “the idea of the spirituals,” and to tell “the story of man using the black figure.” As a self-described “artist reporter,” Crite said his neighborhood paintings aimed to “establish a record, just to show the life of black people in an ordinary setting—to show them ‘just as people’ and not a social problem.”

Related Material

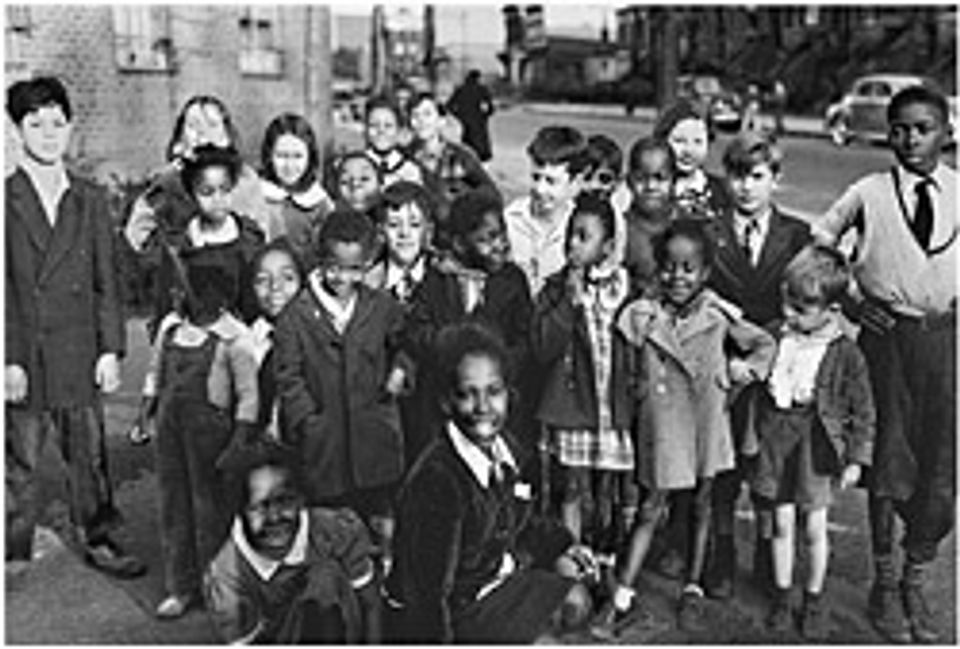

Joe Schwartz, Some World Citizens, Kingsboro Housing Project, Ocean Hill, Brooklyn, NY, 1940s. © Joe Schwartz, Collection of National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Joe Schwartz

Segregation generally created distinctly black and white schools and neighborhoods, but some communities actively moved toward integration. The Kingsboro Housing Project in Brooklyn, New York, was one of the country’s first public housing developments and an early effort to integrate long before what is traditionally called the civil rights era. The image conveys the photographer’s idea that children offer the best hope of people getting along.

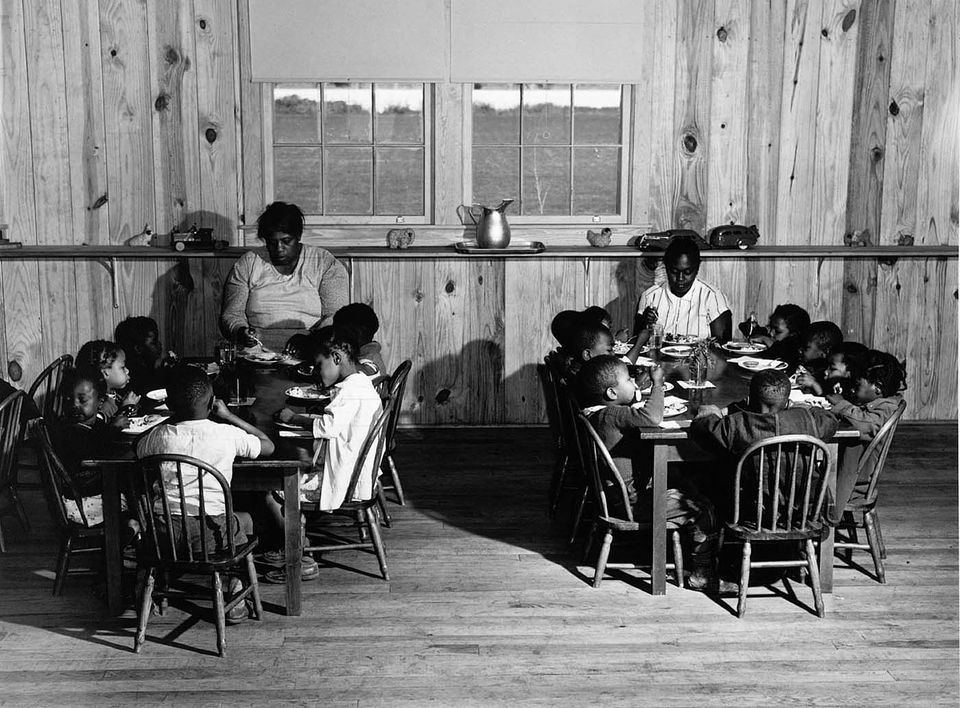

Marion Post Wolcott, Hot lunches for children of agricultural workers in day nursery of Okeechobee, Migratory Labor camp. Belle Glade, Florida, 1941. Silver print on paper, sheet: 11 x 14 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Dr. John H. and Jann Arrington Wolcott, 1998.120.5

During the Great Depression, many people lost their jobs and homes. Some took on seasonal farming work and lived with their families in makeshift camps. Schooling under these conditions was generally nonexistent or dire, but some federal, state, and community-run camps, like this one in Belle Glade, Florida, offered stability and structure for homeless families. The students in this daycare facility ate hot lunches, an improvement over many camps. Although this facility was probably segregated, as shown by the tables with only black children, some camps did away with segregation in an effort to more efficiently address the migrants’ common needs.

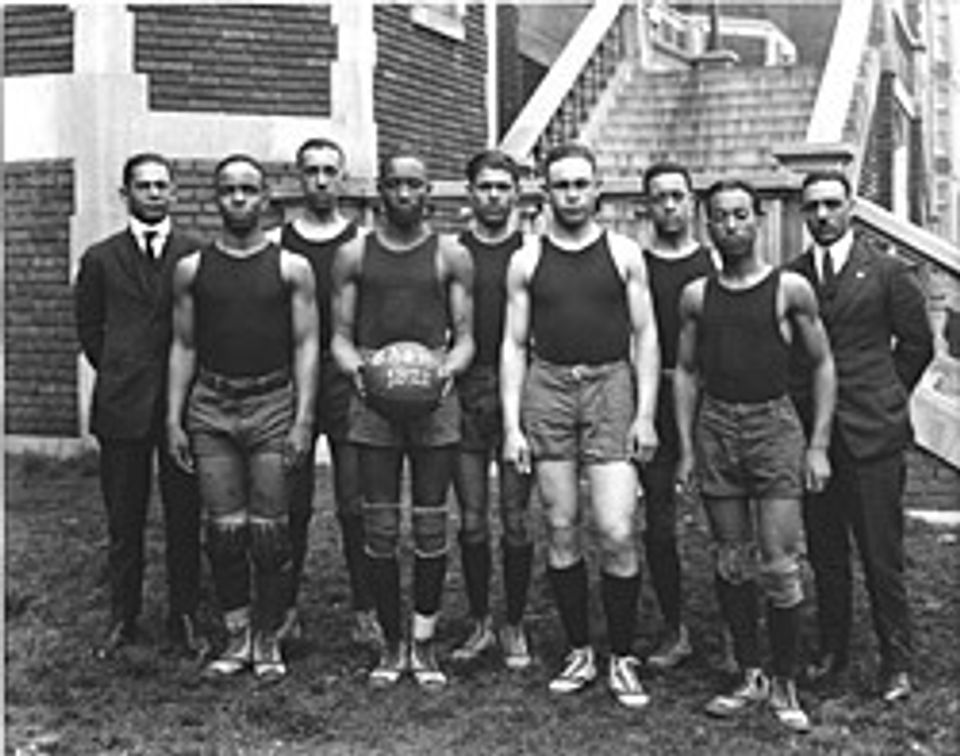

Scurlock Studio (photographer), Charles Drew with Dunbar High School basketball team, about 1922. Photoprint. Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

During segregation, many African American communities, especially those in northern urban areas, built strong schools that advocated the highest quality education as a means to combat racism and inequality. The Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., was the first public high school for African Americans in the United States and became one of the finest in the nation. This photo highlights Dunbar’s championship basketball team and suggests the school’s commitment to both athletics and academics.

Rosenwald Hope School desk, about 1925–1954. National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Hope School Community Center, Pomaria, SC

This desk came from the Hope School in Pomaria, South Carolina, which was built with money from the Julius Rosenwald Fund. The Hope School was one of almost 5,000 Rosenwald schools built in the rural South to provide better educational opportunities for African American children. The Hope School—built in 1925 and still standing today—provides a unique window into this educational initiative and into a small, rural South Carolina community. Despite their poverty and segregation, students and teachers have many fond memories of the Hope School.

Skirt and blouse worn to Little Rock Central High School by Carlotta Walls LaNier, 1957. National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Carlotta Walls LaNier, 2012.117.1ab

When Crite painted School's Out, most schools were segregated, but by mid-century, they also became places where battles over race took place. On May 31, 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the states to integrate public schools "with all deliberate speed" after the May 17 issuance of its unanimous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Two years later, on September 4, nine African American teens - Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Patillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, Carlotta Walls - were turned away from entering Little Rock's all-white Central High School by Arkansas National Guard troops who were called in by Governor Orval Faubus. On September 25, 1957, President Eisenhower dispatched the Army's 101st Airborne Division to escort the "Little Rock Nine" into Central High, where they remained under federal protection for the entire school year. Carlotta Walls LaNier, the youngest of the Nine, wore this new matching skirt and blouse on both September 4 and September 25.