Injecting artwork with medical-grade syringes was not included as part of my job description, yet this is precisely what I found myself doing three weeks into my Conservation Internship for Broadening Access (CIBA) this summer. Conservators are often described as art doctors, and I now understand the almost literal association as I load my medical-grade syringe with diluted consolidant. Objects come into the lab for routine check-ups, examinations, and treatments as necessary. My patient this summer was (and still is) a fantastic multimedia diorama which was part of the 1940 “American Negro Exposition” in Chicago. My fellow CIBA intern, Matthew Fields, and I spent these few months treating this artwork, entitled Reconstruction after the War.

About the Diorama

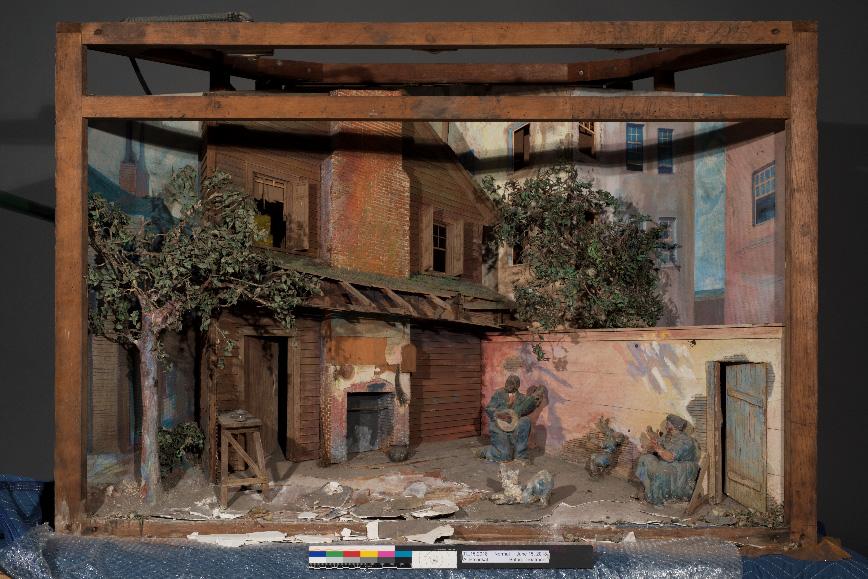

This diorama was one of 33 included in the original exhibition, but only 20 remain today, all of which are in the Tuskegee University Legacy Museum collection. Over 70 African American artists created these intricate works which aimed to depict important moments in African American history. The specific one in our lab this summer is modeled after Eastman Johnson’s 1859 painting, Negro Life at the South, which is in the New York Historical Society collection. With the passing of 80 years between the painting and diorama, the diorama underwent artistic liberties yet the reference to Johnson’s painting is made clear with exceptional attention to detail. After the exhibition, the artwork was placed in a dark basement where it remained for the next 70 years. It came into the Lunder Conservation Center in June needing some extra TLC.

As a pre-program conservation intern looking into master’s programs, I am interested in pursuing paintings or objects as my specialty. I was particularly interested in working with this diorama because of its composition of a variety of materials.

Let me break it down a little—the diorama is constructed with curved Masonite boards nailed to a wooden frame support. All three-dimensional objects in the work are comprised of either wood or plaster or a combination of both. Every plaster figure is connected to the ground with metal poles. The trees are plaster and wire. Each leaf is created from painted canvas cut to shape. Faux moss lines the roof. Almost the entire diorama is coated with a highly sensitive gouache paint. While my wish for more experience in a variety of materials was answered, the diorama had some treatment challenges. When it came into the lab, it was very dusty, and the plaster foreground had completely fragmented. The figures’ painted surfaces were very flaky and at risk for major losses. The plaster walls were cracking and lifting. Many of the leaves of the trees had fallen off. The integrity of the work was at stake, and appreciation of the piece was marred by its aesthetical deterioration. Treatment was, therefore, vital.

Treatment Protocol

So where does the syringe come in? I joked that giving artwork shots wasn’t specifically outlined in my internship duties, but truthfully, diagnosing a treatment plan is a large part of art conservation, and you often have to get creative. Each treatment must be tailored to the object at hand, which can require innovative and resourceful methods and tools—even borrowing from other disciplines and professional fields.

To start treating the diorama, we began full photo-documentation to illustrate its previous state. Step two was a thorough examination, including using ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence, to reveal the helpful material information, and a written examination report. The next step is analyzing the data, testing samples, and making an assessment. Step four, we diagnose—how have the materials degraded and why? What is repairable and what needs to be stabilized? We deliberated these considerations with Lunder conservators to come up with a treatment protocol.

Treatment Process

Before starting the treatment, we essentially had to conduct an archaeological excavation, carefully sorting and cataloguing salvageable fragments among the debris. Next, the diorama needed some serious consolidation (re-binding the surface material to its support). Since every object is unique, cleaning and consolidating agents needs to be tested first to assess its reaction to the object’s materials. At this point, we removed four of the figures from the diorama and treated them as individual objects. Their painted surfaces were very friable, meaning that even a light dusting removed integral paint layers.

The lifting areas of the plaster foreground of the diorama required a stronger and more viscous consolidant. But how do we get the adhesive into those deep angled crevices? Medical-grade syringes proved to be an excellent tool as the long needle was able to penetrate into those hard-to-reach areas and deliver a more controlled application. A few injections of the consolidant, Lascaux, and some deliberate poking set the lifting areas beautifully. With areas of risk stabilized, the diorama was ready for cleaning. After an initial round of light dusting and vacuuming, we tested cleaning solutions.

We’ve got a lot more cleaning ahead of us. This will soon be followed by puzzling the broken plaster pieces back together, restoring broken pieces and fallen leaves, and some light in-painting. Even with a lot of work left to do, the diorama is already looking so much better. I am excited to continue this challenging treatment and am happy to report that Reconstruction after the War will soon be ready for discharge.

The diorama will continue to be treated through October at Lunder. You're welcome to come have a look.

Want to learn more about the diorama? A second blog post on the conservation of the diorama by intern Matthew Fields, will be published shortly.

For more information about the Lunder Conservation Center, check out our upcoming programs and tours and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.