High Kicker (Dancer), Elie Nadelman, 1920, gessoed and painted cherry wood, 28 1/2 x 13 1/2 x 5 in.

New York’s vibrant nightlife became a central theme for Nadelman after his arrival from Europe in 1914. He began working directly from performances he saw in circuses, vaudeville theaters, and dance halls. High Kicker was likely inspired by vaudeville star Eva Tanguay. Nadelman set the figure on a wooden platform to suggest a stage. Her limber body balances on one foot as she twists her head toward an imagined audience. The rhythm of her profile reflects Nadelman’s assertion: “I employ no other line than the curve, which possesses freshness and force. I compose these curves to bring them in accord or opposition to one another.”

The Heron, Joseph Stella, probably 1922, oil on canvas 48 x 29 in.

Joseph Stella had first-hand exposure to Picasso, Matisse, and other European modernists in Paris in the early twentieth century, but by the 1920s he moved beyond abstraction to create portraits and compelling images of nature. “From 1921 on,” he said, “I was swinging as a pendulum from one subject to the opposite one. With sheer delight I was roaming through different fields, spurred by the inciting expectation of finding thrilling surprises.” The Heron shows the majestic bird flanked by exotic flowers. Set against a dream-like landscape, they take on the magical properties of a talisman.

Popocatépetl, Spirited Morning—Mexico, Marsden Hartley, 1932, oil on board, 25 x 29 in.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Partial and promised gift of Sam Rose and Julie Walters When Marsden Hartley arrived in Mexico City in 1932, he studied Aztec and Mayan artifacts and learned the myth of the paired volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl visible on the distant horizon. According to the legend, a Tlaxcaltecas chief promised the hand of his beautiful daughter Iztacc to the brave warrior Popo. Falsely told that her lover had been killed in battle, the girl died from grief. When the young warrior returned, he took her body into the hills and knelt beside her to keep watch. To protect them, the gods covered their forms in eternal snow.

House in Italian Quarter, Edward Hopper, 1923, watercolor on paper, 19 7/8 x 23 7/8 in.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Partial and promised gift of Sam Rose and Julie Walters The summer of 1923 proved a turning point of Edward Hopper’s life. He wandered the rocky shorelines of Gloucester, Massachusetts, and explored the neighborhoods where immigrant Italian fishermen lived. And he began painting in watercolor. House in Italian Quarter is brilliant in the sunlight. The orange facade, blue steps, and lavender shadows reveal a previously unsuspected chromatic virtuosity. At the end of the summer, House in Italian Quarter and seven other watercolors were requested for museum shows, and within a year he was offered his first gallery exhibition. Critics raved and collectors bought, and Hopper's career as America’s best-loved realist was launched.

Horse, Elie Nadelman, about 1913, bronze, 11 1/4 x 11 1/2 x 3 1/2 in.

The classical and vernacular come together in the sculpture of Elie Nadelman, whose sources included antiquities, vaudeville performers, prehistoric cave paintings, and folk art, which he collected in abundance. Horse is stylized and schematic, like the wild creatures ancient artists drew on the walls of caves in Dordogne, France. Yet its prancing pose and abruptly cropped tail are those of an animal groomed and trained for spectacle. Horse relates to a large-scale work Nadelman made for Helena Rubinstein, the cosmetics mogul who helped arrange his escape from Europe to New York at the outbreak of World War I.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Hibiscus with Plumeria, 1939, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Sam Rose and Julie Walters, 2004.30.6

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Partial and promised gift of Sam Rose and Julie Walters. © 2015 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York In 1939, Dole Pineapple Company invited O’Keeffe to Hawaii to do paintings for an advertising campaign. She visited Maui, Oahu, Hawaii, and Kauai, painting the islands’ dramatic gorges, waterfalls, and tropical flowers, among them Hibiscus with Plumeria. Pink and yellow petals towering against a clear blue sky transform the delicate blossoms into a joyous monumentality. But of the twenty canvases of Hawaii she completed, none showed a pineapple. Only after Dole had one flown to New York did she finally, if reluctantly, paint the desired fruit.

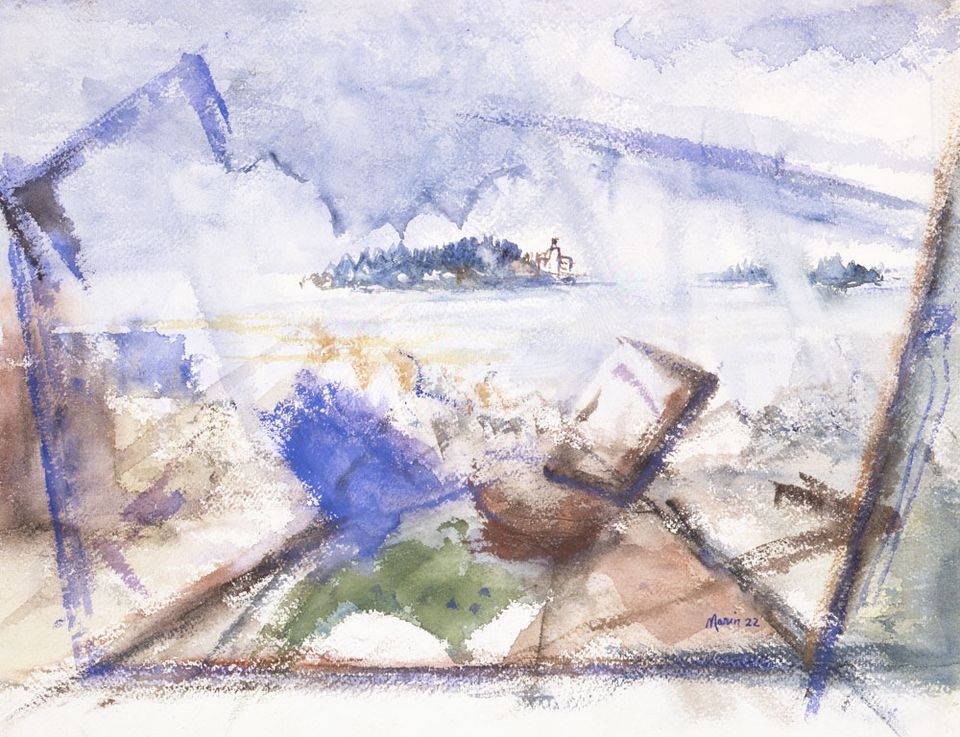

Mark Island Off Deer Isle, John Marin, 1922, watercolor and charcoal on paper, 14 3/4 x 17 in.

John Marin once wrote to a friend, “Scurrying clouds, wind this way blowing, that way blowing … and I like it.” Moisture laden clouds hover above rocky outcroppings; blotted and wiped areas of wet paint suggest wind-driven rain. Although Marin worked outdoors, he often finished watercolors in his studio, relying on memory and imagination. The jagged lines above Mark Island that appear to be a phantom mountain range suggest Mount Desert Island, which is not visible from this vantage point. It was purely a creation of the artist’s imagination.

White Torso, Alexander Archipenko, 1916, bronze, 19 x 4 x 3 1/2 inches

During World War I Archipenko retreated from Paris, where he played a leading role in the avant-garde art scene, to an area in the south of France known for its Roman ruins. Surrounded by antiquities and marble quarries, he used idealized Greco-Roman figures as the basis for cubist statuettes of nude female figures. Their forms underscore his objective: “If muscles or bones interfere with the line, I eliminate them in order to obtain simplicity, purity.” Archipenko carved the first version of the sculpture in white marble and kept the original title when he cast the sculpture in bronze.