Looking back from our vantage point in the twenty-first century, the massive arc of the modern movement dominates the past century. It reshaped all aspects of life and art and permeated every field of endeavor. Modernism’s first expression was rejection—of realism, rationalism, classical physics, and other certainties. In their place, it ushered in subjective concepts and unmoored our visual and philosophical convictions. Artists, impatient to leave behind exhausted traditions, altered not just the “what” of art—its subjects and themes—but the “how.”

The figure of Picasso stands astride the century like a modern colossus. His destruction of figurative traditions was total, and his reconstituted cubist world challenged subsequent artists to populate it with their own inventions. As the works in the Rose-Walters Collection reveal, artists in the avant-garde—Romare Bearden and Stuart Davis are just two—assembled figures and landscapes in a personal, idiosyncratic way, bypassing narration in favor of a powerful, more iconic approach.

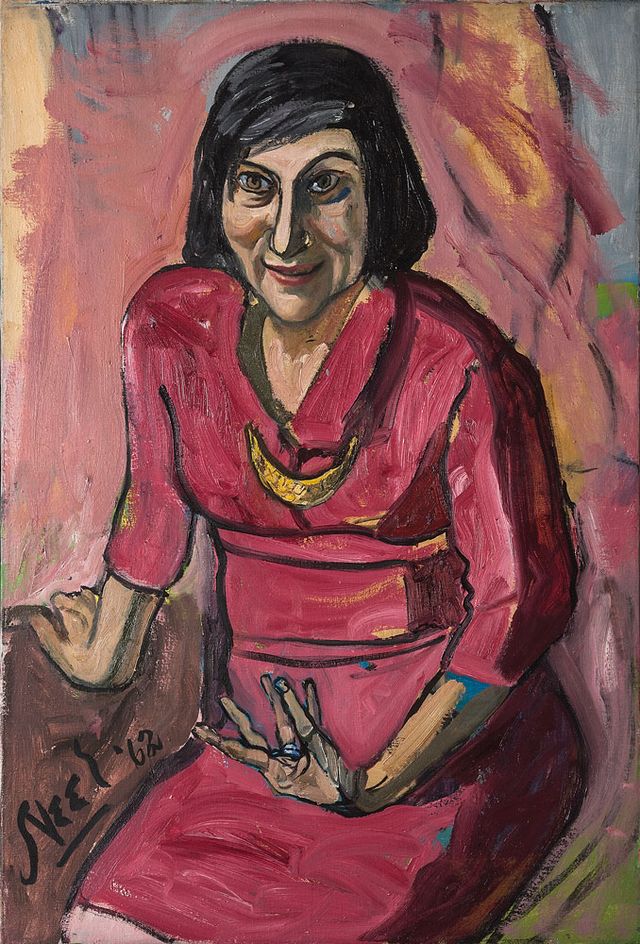

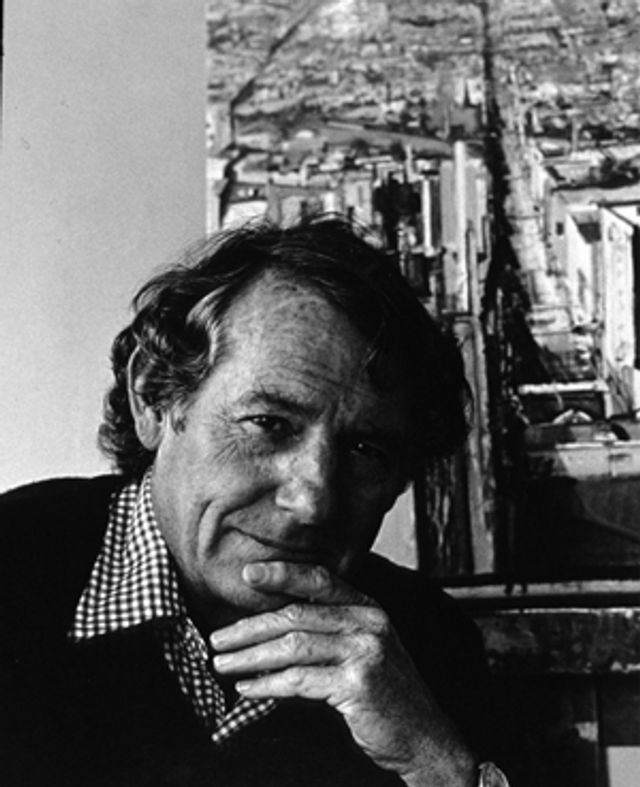

The experience of two world wars; travel by car and plane; and movies, radio, and television that broadcast news and culture around the world brought a new internationalism. Ideas swirled around and circled back as they reached across time and national borders to explore parallel themes. The art and myths of ancient people inflected the work of Joan Miró and Marsden Hartley; nature was the starting point for Georgia O’Keeffe and David Hockney. Picasso and Alice Neel probed likeness and autobiography; Fernando Botero and Roy Lichtenstein make us chuckle in wry recognition. David Smith and Richard Diebenkorn, who explored the materiality of the tangible world, redefined relationships between man and the physical environment. What unites them is their ambition to reach some elemental idea that concentrates the mind on a numinous vision.

Virginia Mecklenburg, Chief Curator

Smithsonian American Art Museum